Productivity, innovation and Review of the Workplace Relations Regulatory Framework

Chairman's speech

Peter Harris gave a keynote presentation to the Australian Labour Law Association Conference on 4 November 2016 in Melbourne.

Download the speech

Read the speech

It is almost twelve months since the Productivity Commission completed its Inquiry Report into Workplace Relations.

The Government has yet to formally respond and given the nature of the topic, that is probably understandable.

We can all hope that the time is being spent wisely.

In many areas of the Australian economy today, what we have in place to encourage the development of the Australia economy at the level of the firm – what we once called micro economic policy ‑ is now the product of many years of compromise.

Compromise in the form of rickety regulatory edifices built on the foundations of solid reformist work done in the 80s and 90s by successive governments.

Governments whose achievements are now legend.

And thus can be treated as legends are: like Camelot, natural perhaps to those far distant times …but unnatural today.

With the implication that expectations of reform should accordingly be lowered.

Of course, to those of us who worked in those reformist times, there was no Camelot, nor even a West Wing, this was no era of low‑hanging fruit.

There was only hard grind against entrenched regulatory advantage; with high cost to any adjustment to that; and opponents desperately attached to failing institutions and systems.

One of these systems was in industrial relations.

Reform was not just the work of the Productivity Commission (or its predecessors) in those days. But certainly most of us who were involved in the reforms that set Australia up for 25 years uninterrupted GDP (Gross Domestic Product) growth acknowledge its role as a catalyst of change, through reductions in trade barriers and exposure of protectionist behaviour.

And the politics of that time was also more comparable to today’s partisanship than is popularly imagined. In truth, while the image of a Camelot may float in the air, there was plenty of politics to go around, as both major parties during their stint in power sought to convince their own supporters to take the medicine, while convincing the broader public that the other lot were rubbish.

And the product of all that work was a flexible economic structure in Australia that persistently lifted productivity and national income, and allowed for redistribution polices that ensured we did not then and still do not today suffer from the languishing incomes for the poorest households and inequality of income distribution that now bedevils the US and the UK; and may be contributing to extremes in political behaviour.

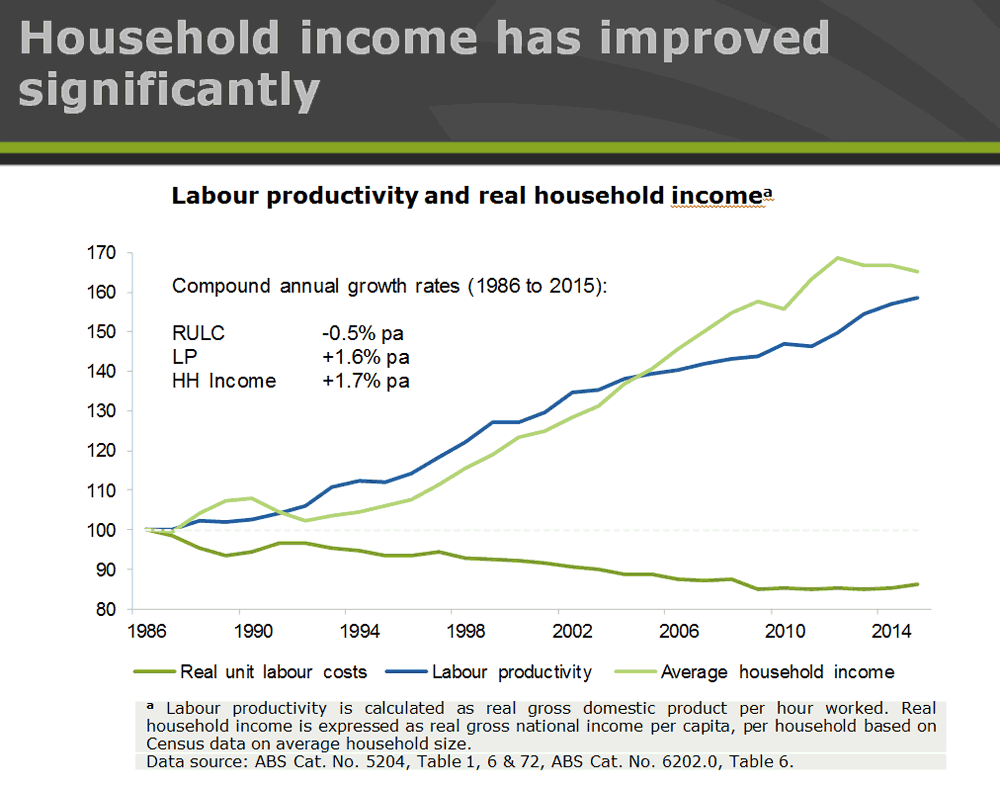

This is a chart we developed for a presentation I gave to a number of governments in South America a few weeks ago, where the Australian reform model (as it’s called there) is, amongst politicians as well as technocrats, an object of near‑universal respect.

Yet that otherwise highly creditable long term combination of falling unit labour costs, rising household incomes and rising productivity contrasts with a very quiet time in economic reform over more recent times, and some odd if not downright unhelpful interventions – some State, some Commonwealth ‑ inconsistent with the public policy that got us where we are today.

Interventions in:

- bilateral trade

- anti‑dumping

- planning and zoning regulation

- gas exploration

- foreign investment

- infrastructure planning…

…raise doubts about the direction of reform, and its substance.

Commentators say that this is just politics today, and are apparently happy to leave it at that.

Thus in workplace relations, while we have all heard that consultation on the Productivity Commission (PC) Report continues, it comes with a nudge and wink that suggests not a lot should be expected.

I’d like to say today that I expect more than that.

The attitude of one or another of the minor parties in the Senate is usually cited as the cause of such low expectations.

But the damaging consequence of such hints is not that little could ever be asked of such disparate interests in the Senate, it is that so little is asked of the major parties, who could between them generate worthy change.

The Workplace Relations Report we produced last year in my view has much in it for both major parties.

Pursuing reforms could return this subject to the status it enjoyed for much of the two decades leading up to Workchoices – that is, an arena in which all the major participants accepted that the reform direction was settled:

- we had a need for continuously improving professionalism in bargaining

- with less dependence on arbitration

- greater recognition that workplace productivity is a shared responsibility between employer and employees

- favouring substance over form in decision‑making

- a safety net that ensures a person in work gains a measure of self‑respect, financially and otherwise, from their efforts.

While it would be wildly optimistic to say that the reforms proposed in our Report could be a vehicle for bipartisanship, let’s also recognise that this has never been the goal of any reform effort, at any time.

It is inevitable, today as it was in past eras of genuine reform, that political parties will emphasise those things on which they differ over the things on which they may agree.

But intense political differences did not stop the passage of legislation that was necessary to reduce protectionism in the 80s and 90s; or to introduce competition in telecommunications and aviation and electricity; or to implement the Hilmer Report on national Competition Policy.

And this applied ‑ grudgingly perhaps, but still it applied ‑ across multiple levels of government.

Putting effort into identifying where we can progress should not stop simply because we cannot truly label this an area of bipartisanship. If no reform can ever take place without bipartisan support, we will be a nation burdened for a long time by stasis.

The catalyst for change then is limited to one rather undesirable option: a crisis.

And the last time we were such a nation – the sixties and seventies – it did not end well. Two recessions, one currency crisis, unemployment and interest rates both above 10%.

The right objective is for the need for continuous reform to be accepted ‑ in this area and in the array of other areas – such as those I cited earlier ‑ where leaders on both sides know the right direction of reform, but have sacrificed the art of negotiation for the science of the wedge.

Policies need to move forward on a broad front, at a time when the rest of the world is certainly not offering to do the Australian economy any favours.

And our own pallid recovery in non‑mining investment is indicating that we have not yet found the encouraging environment necessary for risk‑taking and innovation.

In such a context, the more ‘no go’ areas there are, the more incentive for everyone who has a vested interest to demand that they too become a ‘no go’ area.

Institutional reform in workplace relations – not the alteration of laws to favour one ideological perspective or another, but the alteration of the institution itself ‑ is often for long periods a no go area. And generally it is desirable that institutions are stable for long periods.

But when institutions are not adapted to the environment in which they have to work, the perversity of decision‑making can have major consequences.

In the 80s and 90s reform period, it was evident we had a problem in workplace relations. We could see it, because it took an Accord to break decision‑making structures into economically manageable outcomes.

And so, eventually, we reformed the institution itself. At the time, I know from personal involvement, it took years longer than its authors wished.

We will not see the like of the Accord again and, with no disrespect at all to those who made it work, desirably so. This was not sustainable policy.

And now we have proposed in our recent report to reform the institution again, a mere twenty‑five years later.

…

In Australia, our situation today bears little resemblance to that earlier period of turmoil and disruption.

Some today would say – as we heard quite a lot in the 1980s – ‘if it ain’t broke, do not fix it’. As I used to say at the time, not quite the advice we give ourselves when we put the car in for service, but maybe the national economy is less important.

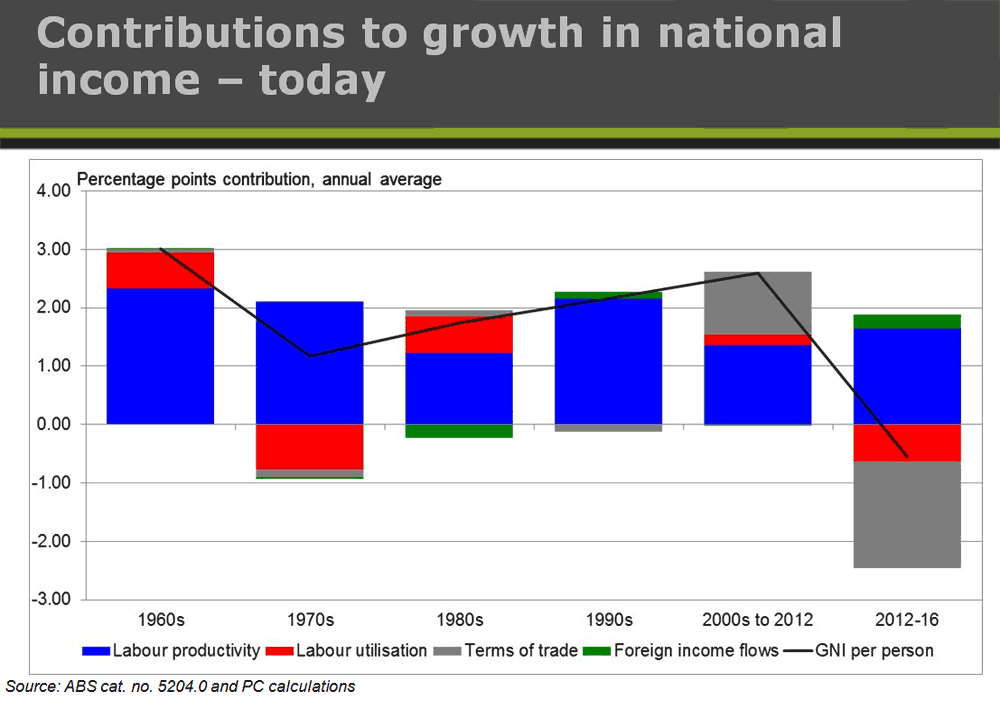

In contemporary times, the major decline in the terms of trade we have experienced since 2012 has seen the national income growth rate falling for some years now, and yet no effort has been made at the policy level to lift productivity and offset this.

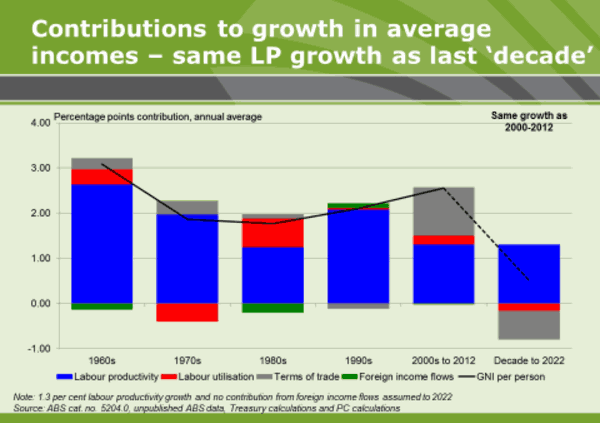

When I started this job in March of 2013, I made what some suggested were productivity forecasts in my first speech.

They were not forecasts, merely a representation of what would happen if labour productivity did not lift strongly in the second decade of the 2000s to offset the expected decline in the ToT (Terms of Trade), after a poor performance in the first decade of this century.

If labour productivity simply recovered to its long run average, I suggested, the terms of trade decline and slowing labour market participation due to an ageing population and weaker hours worked would still see national income growth halve.

Growth, sure, but half its long run level.

Today, the revised figure looks like this.

Bottom line is, the 2013 projection now looks pretty optimistic.

Some might say I was shooting fish in a barrel, the terms of trade decline was going to cause this downward shift in income regardless of what productivity did.

And there is a bit of truth in that, but only a statistical truth.

Yes, the ToT decline was always going to be ugly, when it arrived.

But no, for productivity we did not have to limit our objectives to simply hoping for recovery from the bad performance of the 2000s, back to the long run average.

We could have aspired to much more. We did not.

And while labour productivity has returned to average – not perhaps a traditional benchmark for celebration ‑ income growth still declined. Seriously, some might say.

We should have aspired to more 3 years ago, and we still should do so today.

..

Labour market reform is not the only, nor even the largest productivity‑enhancing reform we could undertake.

But it is the one most iconic in terms of showing that Government and Opposition might still be able to agree at times, and demonstrate to a jaded public that it is still possible for policy to move forward without a wedge.

I mentioned a little earlier the agreed direction for improving the Workplace Relations (WR) system that had applied until the last decade of hyperactivity, created by Workchoices.

These shared interests were:

- professionalism in bargaining

- less dependence on arbitration

- substance over form

- recognising workplaces are shared responsibilities

- safety nets, to support the dignity of work.

If we are wise, we can find a set of such changes that match these standards in the Commission’s 2015 report.

Today, I’m going to point to a few that I believe can easily meet the tests I’ve set.

But I do so only to illustrate what should be achievable, despite any politics of difference.

As Chairman of the PC, I’m never going to advocate cherry‑picking our reports.

The issues are the issues and the solution are the solutions, and I’ve seen nothing in subsequent commentary in the past year to persuade me that we got anything of substance wrong.

But in order to make the case that agreement is possible, despite political differences, in a 20 minute time‑frame, I can only highlight a few obvious candidates.

Workplace Standards Commission (WSC)

The idea of breaking the Fair Work Commission (FWC) up into two bodies is driven by a simple and strongly evident fact: the FWC is currently charged with two economy‑wide decision‑making processes ‑ the awards modernisation process; and the setting of the Minimum Wage – both being wage‑setting arrangements.

They are quite different in nature to its other work ‑ different in skills and in culture to the legally‑driven dispute settlement and agreement approval work.

We say in the Report, and do so with quite strong evidence, that decisions of an economic nature – setting the base price of labour across the economy, judging how to structure a modernised award ‑ are being substantially driven by building on precedent rather than on evidence.

The language of decisions is couched as being ‘not persuaded’ by any new evidence, thus indicating that it is always the prior view that must be dislodged, rather than a fresh view taken of the matter.

And while some weight is given to expert opinion, it is not the quality of the expertise that determines whose view is considered, but whether they are nominated as an expert by the parties to the process. This necessarily limits the quality of the evidence received to being partisan, almost inevitably.

Panel members themselves must otherwise bring their own expertise to bear, but they are not helped in doing this by the lack of an independent research capability. Like the judiciary, they do not investigate the evidence themselves – but they should.

Given the significance of the price being set, in the public interest one would normally seek to have as much independent advice as possible, rather than skew the system towards a choice amongst partisan views.

The award modernisation process is similarly limited. Expert advice of an independent nature is not brought to bear on variations, and quite deliberately so. Since it is cost‑free to a participating party not to agree to a variation, a lowest common denominator change process is inevitably locked in.

Those imbued with the spirit of the system as it is today do not find this exceptional.

Those who work in the field of good public policy design find it quite shocking.

There will inevitably be costs imposed and flexibilities lost, as well as inequities perpetuated.

Creating a WSC would allow a shift from the legal culture of not overturning precedent to a whole‑of‑economy view – a view of the kind that has otherwise prevailed for some decades in this economy and given us this 25 years of uninterrupted growth.

Some Commissioners of the current FWC would be well‑suited to work at the WSC, others would remain with the dispute settlement and arbitration entity. Most valuably, a culture of searching independently for the full weight of evidence could be embedded.

Transfer of Business

It is an extraordinary thing to find in the course of an inquiry like ours that the workplace relations system does not offer to the otherwise powerful decision‑makers in the FWC the discretion to make a decision that favours on‑going employment over redundancy, such as in circumstances where a firm is going broke.

I will not specify the full detail as its complexity is beyond a speech of this kind, but section 309 and 318 of the Fair Work Act fail any common sense test that I can imagine.

Greenfields

A surprisingly high percentage of new Enterprise Agreements are greenfields agreements. The most important amongst these are large fixed investments in infrastructure.

We proposed that agreements should match the life of the project. This might seem common sense but the system does not allow for that kind of new fangled thinking.

We also proposed a mechanism that offers clear incentives to the parties not to draw out negotiations and so stymie investment and new jobs.

I particularly like last offer arbitration, but there were three options recommended. And they each applied incentive choices to both union and employer.

Four‑year review process

There was bipartisan cheering in our lock‑up in Canberra last year when the recommendation to abolish the four‑year award modernisation process was put up on the screen. The general consensus is that this process has run its course.

We propose that the WSC take over the task and do so by reference to independent research (such as our weekend penalty rates analysis) into clear areas of contention where benefits of change may be high.

It means in effect that future analysis should follow substance rather than form. Only awards affected by the change would be under review, reducing the major call on resources of all parties to the 4‑year reform model.

Inadvertent Errors

We proposed that the FWC should have the discretion to overlook a procedural error or mistake that in its view had no bearing on the outcome of an agreement process.

Again, for a system so empowered as to make large discretionary judgments about the cost of labour, it is quite odd that lesser judgments that could avoid the system being legitimately castigated as inefficient are not on everyone’s agenda.

Independent Contractors

We proposed that it should be made unlawful to misrepresent an employment relationship as a contractor role when it was not, and an employer could reasonably be expected to know otherwise.

Moreover, we also proposed an Enterprise Agreement not be able to restrict the use of legitimate contractor employees.

There is at least the semblance of a quid pro quo here, where the current law is in a poor state to deal with problems from both employer and employee perspectives.

Migrant Workers

It is obvious from the 7‑11 Fair Work Ombudsman investigation and other examples in some food processing industries that migrant workers are very exposed to exploitation, and current law is insufficient to deal with these circumstances.

We made a series of recommendations to deal with this. None of them should be contentious, all of them would add a socially positive angle to a package that should draw wide support.

..

I am surely at my time limit and so do not propose to go further with examples.

My intention is to leave with you with the message that there is scope for reform in both this and in other important fields, that might collectively lift our national productivity.

Not change that involves erosion of conditions or tilting of the negotiating table in favour of one party or another, but change that – along with other reforms – seeks to reverse the decline in national income growth, and preferably reverse it.

Speech

Commissioner Catherine de Fontenay delivered a speech to the 2023 Tasmanian Economic Forum.

Download the speech

Read the speech

As you’ve probably gathered from my accent, I’m not from around here! But I am married to a Tasmanian. He grew up in Burnie, in the heyday of large-scale manufacturing there. It’s funny, many of us wax nostalgic about the glory days of manufacturing … but the ocean water was brown because of the residue from the pulp and paper mill; and if the wind was in the right direction, and you were downwind from the sulfuric acid plant, you’d get a strong tingling sensation in the back of your throat. And if you went mountain biking behind the paint and pigment factory, the forest had been completely killed off and it looked like a moonscape.

So if the good old days of manufacturing were not quite as good as we remember, why are so many of us worried about the shift from manufacturing to services? Tasmania after all, like the rest of Australia, has had a long-term shift away from manufacturing and toward services, and Tasmania’s manufacturing sector is performing a useful support function for agriculture and mining, but it’s relatively low productivity. What is it we’re actually worried about?

First, making stuff is cool. I’m very sympathetic to this view, being from Washington DC, a town that produces nothing but hot air. A brilliant Tasmanian architect selling their designs overseas doesn’t have the same tangibility as a manufacturing export.

During Covid, we worried about being dependent on overseas supply chains for manufactured goods. The Productivity Commission did a study of that issue and found that there are only a small number of products where global production is overly concentrated. Relying on global trade means supply can come from a whole range of countries, some of whom can respond to a shock more quickly than we can.

Of more concern is that manufacturing used to offer a route to building skills and earning a good income for those who didn’t get much formal education. The decline of manufacturing means fewer paths to a high-income job for those who didn’t get much education. There are still paths to good jobs through trade apprenticeships and some paths through health, and those are big sectors. But for the rest of workers, the path to a better job is through taking VET courses to upskill (possibly in an area you’re not currently working in). So all of these paths rely on VET being affordable, accessible, and high-quality. Even with good VET, upward mobility is an ongoing policy challenge, for all of Australia, as job markets become increasingly polarised.

Finally, there is a geographic concern, because a shift from manufacturing to services shifts the locus of activity:

- Some economic activity has shifted away from input locations in manufacturing, like the North West of Tasmania; and so the employment options in those locations are worse.

- Economic activity also shifts towards cities, specifically the big cities of the mainland with several universities, that create knowledge economy jobs (for example, finance, professional and technical services).

So some of those concerns are reasonable. That said, policies to slow or reverse the shift to manufacturing have lots of negative consequences. And there is also lots of potential good news in the shift toward services.

First, in terms of the geographic shift, it’s potentially good news for some smaller cities. Even before remote work, some smaller locations became hubs of knowledge work. In the US this includes locations such as Austin Texas, Raleigh-Durham in North Carolina, Boulder Colorado, and so on. There needs to be a good university (for hiring smart graduates and as a source of expertise and new startups), and appealing location to high-income workers.

So in Tasmania, this means that the Hobart region has strong potential if investments are made in boosting the quality of teaching at University of Tasmania and the involvement of academics with the private sector (academics involved in consulting, academics involved in startups).

The same could potentially be said of Launceston. The Commission has made a number of recommendations that the University could implement itself, with encouragement from Tasmanian economists: making all lectures available online to the university community or even better to everyone; real rewards for good teaching (grants and bonuses); allowing academics to consult and to easily license their intellectual property.

More recently, the rise of remote work (and of course climate change) raises the attractiveness of all of Tasmania as a location.

The message is that attracting high-income knowledge work is about attractive locations (the growth in the Tasmanian tourism industry has helped make many locations more appealing), telecommunications and digital infrastructure and SKILLS – attracting retaining and building skilled workers. (I want to stress, the interest in attracting this work to Tasmania is not because high income knowledge work is the only sector of interest, but it’s high productivity and it boosts demand for many other services.)

There is also a tremendous amount of good news for Tasmania in another major shift we are experiencing, the shift to more services being available online.

The shift to online is good for workers

First, the shift to online study. Lots more VET and Uni courses are available online than before Covid. I counted 20 different online TAFE accounting courses, for example. There are also lots of e-learning courses from reputable firms with industry expertise for upskilling and even entering a new industry. This means that there are more paths for people to upskill, and more industries that they can access. It also means more competition for local University and VET courses.

It’s useful that Tasmania was early in the NBN rollout, so students in most locations can access the internet. But Australia is still missing a key ingredient for online: we need good mechanisms to ensure quality in online VET and university. Students need information on the quality and cost of all available courses.

As the Commission has pointed out, the websites to guide students to VET courses are deeply terrible. And the VET regulators (ASQA) are very focused on compliance rather than quality. I would love to see ASQA and TEQSA actually attend some classes in the institutions they regulate!

Next, the shift to online work

That means lots more jobs available in depressed areas, thanks to online options. The transition hasn’t fully happened yet; at the moment there are more people interested in working from home than there are jobs, depending on the type of work. For example, an online health provider advertised 20 work-from-home nursing and allied health jobs, and got 500 applications. But there will gradually be more and more work available purely online. But taking advantage of these online jobs requires literate and internet-savvy workers; and we still have some students leaving school with serious weaknesses in their literacy and computer skills. So Tasmanian school and VET options need to be high quality for all students. More on school quality later today!

The shift to online is good for businesses

I think Tasmanian firms are aware that they need to be online and oriented toward bigger markets on the mainland and overseas. This is a big advantage over mainland firms. And the ease of getting one’s business online really helps.

Online is important for the diffusion of technology: The main way that firms learn about innovation is from other firms in their industry. That’s challenging in Tasmania, when those firms may be further away.

There are a number of ways that the internet can help with that challenge. Staying more digitally connected to professional associations, relevant university researchers on the mainland and overseas, can be really valuable. Firms can attend online events and lectures. Firms can also access more skilled intermediaries from the mainland and overseas: consulting firms, skilled accountants and other intermediaries. There is value in using intermediaries that other firms in the industry are using, because they share information. There are benchmarking services (including one from the ATO) that allow firms to see how they’re performing relative to their industry.

And an online presence makes it feasible to hire workers from the mainland and overseas; for some roles, they may not even need to relocate. Firms can gain both specialised skills and specialised knowledge of sophisticated processes at other firms when casting a wider net in hiring.

What is the role of policymakers and economists in all of this? Policymakers can support the growth of professional associations, especially ones with ties to the mainland; they can provide more industry-specific information about what’s available online; they can support the migration review.

Finally, the shift to online is good for consumers

It’s worth remembering that the benefits to firms that I’ve described also flow to their consumers. Lots of products and services are available from online providers, and this provides a valuable check and balance on local market power: there are lots of areas where there are a small number of firms supplying the market. Again, it requires literate and online-savvy consumers with internet access.

In short, I think some of the broad shifts that we identified in Advancing prosperity have tremendous potential for Tasmania, if there is the right policy response. Supporting people to develop their skills is at the core of that policy response.