Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2016

The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report measures the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

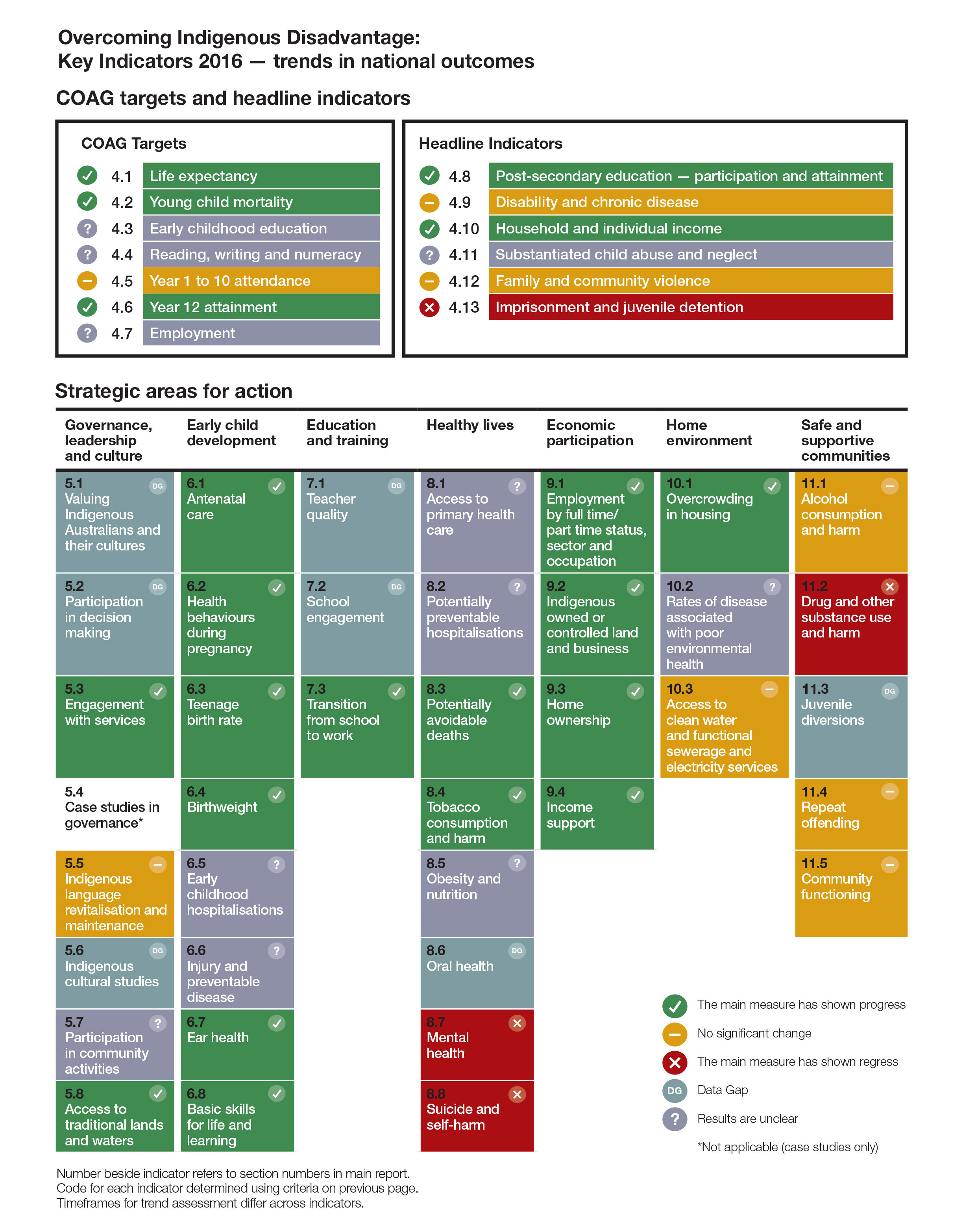

This comprehensive report card measures where things have improved (or not) against 52 indicators across a range of areas including governance, leadership and culture, early childhood, education, health, home and safe and supportive communities, and includes case studies on things that work to improve outcomes.

The report is produced in consultation with all Australian governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

The 2016 report was released on 17 November 2016.

Please note: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are advised that this website may contain names, images and voices of deceased people. It may also link to other websites which contain names, images and voices of deceased people.

At A Glance

Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage 2016

The 2016 Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage (OID) report shows some positive trends in the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, but also shows outcomes have stagnated or worsened in some areas.

Two years on from the previous report there continues to be improvement in many areas of health, economic participation and aspects of education. But areas such as justice and mental health remain concerning, with increases in imprisonment rates and hospitalisations for self-harm.

“It is encouraging to see improvement over the last decade in rates of year 12 completion and post school education. But alarmingly the national imprisonment rate has increased 77 per cent over the last 15 years, and hospitalisation rates for self-harm have increased by 56 per cent over the last decade” said Peter Harris, Chair of the Productivity Commission and of the Steering Committee.

The OID report continues to provide comprehensive reporting, with a ‘strengths-based’ focus. It also includes some case studies on ‘things that work’ to improve outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. “If we are to see improvements in outcomes we need to know which policies work and why. But the overwhelming lack of robust, public evaluation of programs highlights the imperative for Indigenous policy evaluation” said Deputy Chair Karen Chester.

The OID report should be compulsory reading for anyone interested in the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, including those working in service delivery or program design.

It is the most comprehensive report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing produced in Australia. It covers areas including governance and culture, early child development, health, education, economic participation and safe and supportive communities as well as reporting on indicators related to the Closing the Gap targets.

The report is produced by the Productivity Commission for the Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians involved in its development. This report is the seventh in the series.

The 2016 OID main report, Overview and short video can be found at: www.pc.gov.au\oid2016

- This report measures the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, and was produced in consultation with governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Around 3 per cent of the Australian population are estimated as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin (based on 2011 Census data).

- Outcomes have improved in a number of areas, including some COAG targets. For indicators with new data for this report:

- Mortality rates for children improved significantly between 1998 and 2014, particular for 0<1 year olds, whose mortality rates more than halved (from 14 to 6 deaths per 1000 live births).

- Education improvements included increases in the proportion of 20–24 year olds completing year 12 or above (from 2008 to 2014-15) and the proportion of 20–64 year olds with or working towards post-school qualifications (from 2002 to 2014-15).

- The proportion of adults whose main income was from employment increased from 32 per cent in 2002 to 43 per cent in 2014-15, with household income increasing over this period.

- The proportion of adults that recognised traditional lands increased from 70 per cent in 2002 to 74 per cent in 2014-15.

- However, there has been little or no change for some indicators.

- Rates of family and community violence were unchanged between 2002 and 2014-15 (around 22 per cent), and risky long-term alcohol use in 2014-15 was similar to 2002 (though lower than 2008).

- The proportions of people learning and speaking Indigenous languages remains unchanged from 2008 to 2014-15.

- Outcomes have worsened in some areas.

- The proportion of adults reporting high levels of psychological distress increased from 27 per cent in 2004-05 to 33 per cent in 2014-15, and hospitalisations for self-harm increased by 56 per cent over this period.

- The proportion of adults reporting substance misuse in the previous 12 months increased from 23 per cent in 2002 to 31 per cent in 2014-15.

- The adult imprisonment rate increased 77 per cent between 2000 and 2015, and whilst the juvenile detention rate has decreased it is still 24 times the rate for non-Indigenous youth.

- Change over time cannot be assessed for all the indicators — some indicators have no trend data; some indicators report on service use and change over time might be due to changing access rather than changes in the underlying outcome; and some indicators have related measures that moved in different directions.

- Finally, data alone cannot tell the complete story about the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, nor can it fully tell us why outcomes improve (or not) in different areas. To support the indicator reporting, case studies of ‘things that work’ are included in this report. However, the relatively small number of case studies included reflects a lack of rigorously evaluated programs in the Indigenous policy area.

[Scene set in a television studio]

FLOOR MANAGER: Going Live in 5 guys!

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER: So, Rachel, I was thinking today with our justice story…

RACHEL: I’m still making some changes.

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER: So, am I going to get the changes before or after the program?

RACHEL: You know the drill – point the camera in my direction.

[Some scenes showing Uncle Jack Charles making his way to the studio]

FLOOR MANAGER: OK Rachel! Can someone get her miked up please! 4 minutes 30.

RACHEL: Hello, my name is Rachel Rockling and welcome to National Indigenous News. Tonight: Harry the Stockman – a big man with a big heart, and Johnathan Thurston - is he the best human ever?

FLOOR MANAGER: Camera 2 can you go wide please? Is that somebody in the background there?

RACHEL: Hey. Jack Charles? You know we are live here Uncle Jack.

JACK CHARLES: I just want to come chat to you about the Productivity Commission’s…

RACHEL: This is my show Jack! My show.

JACK: It’s an exclusive! An exclusive for just for you Rachel Rockling.

RACHEL: Oh, an exclusive hey? Well I guess… An exclusive you say?

JACK: Yes

RACHEL: Well I guess I can accommodate you then Jack - Uncle Jack isn’t it?

JACK: Yes Yes Yes

RACHEL: Can I call you that?

JACK: Yes Yes Yes – better than Aunty Jack ay.

RACHEL: Ha Ha Ha – Uncle Jack!

JACK: Thank you.

RACHEL: Let’s hear of your exclusive… when you join me… after the break.

-----

RACHEL: OK, so we’re back with Indigenous screen legend Jack Charles, with an exclusive just for me… I mean us at National Indigenous News! You comfortable Uncle?

JACK: Oh yes very comfortable thank you Rachel. So, I’m here to speak about the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report. Now this report measures the wellbeing of our mob.

RACHEL: Yes?

JACK: It really is the most comprehensive report on our wellbeing produced here in Australia so far and it has real depth of analysis too. I mean, there’s been so much work put into this by the Productivity Commission – it blows my mind! They are the Productivity Commission after all ay!

RACHEL: Yes, Yes. It’s good to be productive.

JACK: Yes, this is all good stuff Rachel. They have masses of information on the Productivity Commission website, but if you want a quick Overview they have one of those too. You can take a look through the Overview and then check the website if you want more detail.

RACHEL: It’s great they’ve got an Overview, but even so, some of these reports are hard to digest for the average person that works in the Indigenous industry with our mob on the ground. We are all busy and don’t have time to wade through pages and pages of research needlessly. This generation has been recently criticised for having bad attention spans. How does this report fare in that department?

JACK: Well Rachel, this report is really accessible, with key findings, graphs and even case studies that work. The overall aim of this report is to provide information that we can use to improve the wellbeing of our mob, and I think they've done it pretty well. It’s really good, for any generation, or any attention span.

RACHEL: Oh yes. Tell me more?

JACK: Well you know, it doesn’t sugarcoat the outcomes but it does provide a balanced picture – some things are getting worse, some things are getting better, and even talks about strengths. Also, the report tells you what information we can use to improve the wellbeing of our mob – like good quality evaluation of programs so we know what’s working and why.

RACHEL: Deadly Uncle! That sounds really good. But tell me, was there any Indigenous involvement in this?

JACK: Oh yes, us mob were involved, from all over Australia.

RACHEL: That sounds great. So, I really can use this report in a practical way then? For research into my hard hitting, fearless news stories perhaps?

JACK: Yes. If you or someone else work in an organisation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander outcomes in mind, you absolutely have to have this report.

RACHEL: Well, you’ve sold me Jack. I’m going to go check it out after my bulletin tonight. No idea how you got past security but I’m glad you did!

JACK: You know I’m pretty crafty.

RACHEL: Thanks for your time Uncle Jack.

JACK: Thanks Rachel. Great hair by the way.

RACHEL: Thanks Uncle. And next time, use the front door.

Up next on National Indigenous News, how Blackfellas have embraced the online world.

-----

NARRATOR: To get the report and explore the areas of Indigenous wellbeing that interest you, go to pc.gov.au/OID2016, or find us on Facebook by searching for 'Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage'.

The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report is produced by the Productivity Commission on behalf of all Australian Governments.

This video was produced by NITV on behalf of the Productivity Commission.

-----

[looking at the Productivity Commission website]

UNCLE JACK: See Rachel – I told you. This report is so comprehensive!

RACHEL: Another exclusive coming up, thanks to the Productivity Commission!

[the end]

Printed copies

Printed copies of this report can be purchased from Canprint Communications.

Publications feedback

We value your comments about this publication and encourage you to provide feedback.