Here to help: the role of economics in contemporary policy challenges

Speech

Chair Danielle Wood delivered a speech at the Australian Public Service Economist Conference on the 25 November 2024.

Download the speech

Read the speech

I would like to begin today by acknowledging the traditional owners of this land, the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation. I pay my respects to their Elders past and present, as well as to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people joining us today.

Thank you to the Chief Economists and Economics APS Community of Practice, as well as the Faculty of Business and Economics for organising this event. I’m not sure I have ever been in a room with so many economic policy nerds but it is a delight to stand here this morning among friends.

Thank you to Gordon for braving it, and for that wonderful opening.

I’ve written my thoughts down today, partly to make sure I’m coherent but also because I don’t get many opportunities to write these days and it’s a part of policy life I very much miss.

A big thank you to Carmela Chivers and Patrick Commins, and other insightful PC colleagues for helping me bash my words into shape.

Once upon a time….

Before I get to the here and now, let me start with a trip through the recent history of Australian economic policy advice.

I think it is fair to say that economists held an outsized role in shaping Australian public policy in the post War period.

During the so called ‘golden era’ of reform in the 80s and 90s, economists like Ted Evans, Bob Johnson, and Bernie Fraser lit the path for Prime Ministers to transform Australia into the open, trading nation that we are today.

Under their guidance we floated the dollar, deregulated the financial sector, introduced a Goods and Services Tax and opened Australian markets to competition.

Also a hat tip to Alf Rattigan, the head of the Tariff Board and then the Industry Assistance Commission – the PC’s predecessor organisations – who took an agency focused on calculating rates of assistance to industry and turned it into an influential advocate for opening Australian industry and trade to the world. 1

And through those years, the Australian public were up for the discussion. Thus the famous Paul Keating line, that if “you walk into any pet shop in Australia, the resident galah will be talking about microeconomic policy”. 2 These days, I despair it’s hard to get a human, let alone a bird, to have a causal chat about structural reform.

Back further, in the post-war reconstructionist era, the federal public service was dominated by the so called ‘Seven Dwarfs’ – a group of short-statured but high-powered departmental secretaries who built our policy agenda over several decades. 3

Of the seven, four were trained economists: Sir John Crawford, Dr HC ‘Nugget’ Coombs, Sir Roland Wilson, and Sir Richard Randall (and Sir Frederick Shedden did commerce – almost close enough to claim him).

Although many of their policy prescriptions wouldn’t be right for the times now, the Dwarfs’ intellectual heft and capacity to respond to the circumstances of the day has given them mythical status in Canberra.

The economy we’re living in now faces many new challenges – the net zero transformation, the ageing population, and the disruptor that is AI.

Responding to them will require us to bring the best of our predecessors to the table – rigorous frameworks, and the courage to make the case for hard reforms even where they may be unpopular or might not seem obvious.

And so, since we’re among friends, I’m going to do something today that I usually wouldn’t endorse: a bit of navel gazing.

I want to explore with you the capacity of the economics profession in Australia – all of us in this in this room – to meet the high bar set by those who came before us. How will we perform in informing the big policy questions of the next twenty years?

The task isn’t an easy one. The environment we operate in is different to times past: economic, social and environmental policy problems are increasingly intertwined, making policy prescriptions more complex and implementation a more important part of the policy process.

I think it is also true that economic advice is increasingly contested: the profession is at a lower ebb in esteem in policy making and broader circles. Partly this is a reflection of fair questions about our blind spots, but it also reflects a preference of some to avoid some of the inconvenient truths that economic frameworks can deliver.

I will argue that there are many positives in the way that the economics profession has evolved that can set us up for success. But there is also scope to do better, particularly on making sure our advice is practical and clearly communicated. We also have serious work to do on our pipeline to ensure that we attract the best and brightest to economics.

Losing its cool: economics shares the limelight in modern policy making

There are many jokes about the social skills of economists. Economists are accountants but with less charisma, an extroverted economist is one that looks at other people’s shoes…I could go on. But while we might not be the coolest people at the party, as we’ve seen, economists have historically been unambiguously at the centre of policy making.

This has changed somewhat. It is clear that economists still wield a lot of power in key debates, but there is a greater contestability and also a greater degree of scepticism of economic prescriptions.

The scepticism ranges from mild questioning to outright hostility. The failures of economics have unleashed an almost infinite number of words and column inches….

How should we reflect on this change?

I think the first thing to note is that at least some of the criticisms levelled at economists are well justified: most failed to foresee the GFC, many missed the rise of China, our multilateral organisations blindly rolled out the same policy prescriptions from capital account liberalisation, slashing government spending and privatisation for a range of countries with little regard to their context or history. 4

For a long time, many economists have been wilfully blind to questions of distribution – arguing ‘it’s not our job’ to consider economic inequality, let alone exploring the feedback loops between inequality, mobility and growth. 5

And in Australia, many hold economists responsible for the policy failures in human services markets. Our faith in markets to deliver better consumer outcomes – saw us throw open the door to private providers in areas like vocational education and training, employment services, and the National Disability Insurance Scheme, without enough emphasis on market design or regulation, leading to bad outcomes for vulnerable consumers and a padded bill for taxpayers.

My second observation is that this ‘sharing of the spotlight’ represents a very appropriate evolution given that major policy challenges have evolved.

The most pressing policy problems today – including economic policy ones – are often more complex than in previous decades.

‘Wicked problems’ like climate change, housing affordability and closing the gap in outcomes for First Nations Australians are front and centre – as they should be.

And these, and many other important policy challenges, cut across other policy realms.

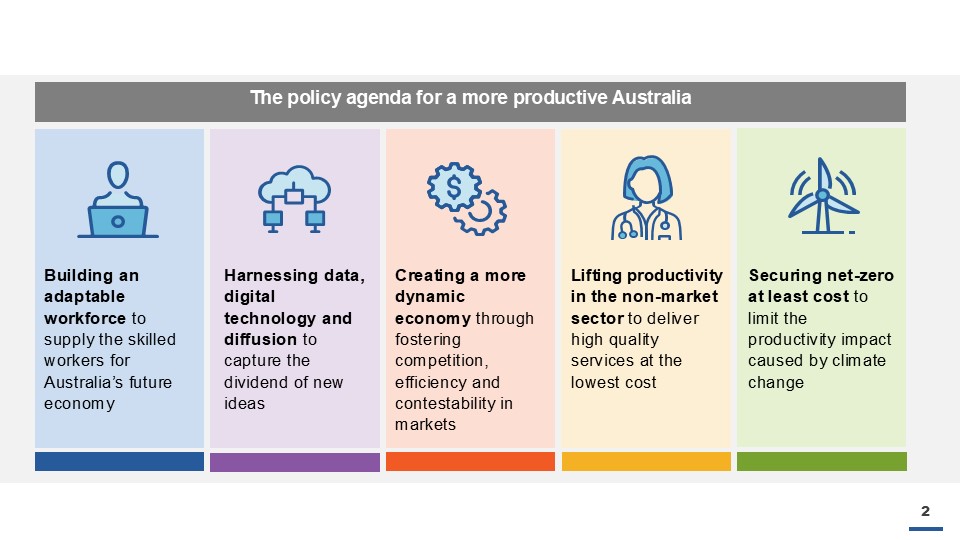

For example, the PC’s most recent 5 yearly productivity inquiry identified 5 key ‘themes’ where policy changes could make the biggest difference to productivity: building an adaptable workforce, harnessing data and digital technology, boosting economic dynamism, lifting productivity in the non-market sector and favouring lower cost policy options to reach net-zero.

These align nicely with what the Treasurer discussed just a fortnight ago as the ‘5 pillars’ of productivity. 6

Almost all of them involve cross-cutting and complex discussions across spheres involving technology, social and/or environmental policy.

In this environment, it is necessary to draw on a broad range of expertise in policy making. As I’ll come to later, economics itself continues to evolve to take account of and build in knowledge from other disciplines.

But the third reason for rejecting economics in policy making is less justified and should concern us.

Economists can be a pain in the arse.

Our focus on trade-offs, demand for evidence on costs and benefits, and our penchant for pointing to the potential for unintended consequences, can be tiresome for those who would prefer less scrutiny or more decisions on the ‘vibes’. It’s always tempting to convince yourself that the easy thing to do is also the correct thing. 7

Economics remains a powerful antidote to ‘magical thinking’ that can often prevail in the policy world. We should be wary of those who would like to silence it because they would prefer less scrutiny.

We need economics to solve modern policy problems

The rigour and clarity provided by economic frameworks are the reason I think economics has an important role to play.

Economics offers insights about how choices are made by individuals, households, and governments in the use of their limited resources.

And that basic proposition is just as true for many of our modern policy debates as it has been of our old – from industry policy to AI regulation, to the net zero transition to the future of the care economy.

I’ll illustrate today by just focusing on one of these: the debate around modern industry policy.

I choose this one for two reasons.

First, it is an example of where the backlash against economists and economic frameworks has been particularly acute. In the past 6 months, the contributions the Productivity Commission and others have sought to make to the debate on industry policy have been labelled everything from ‘out of touch’, to being in thrall of ‘neo-liberal orthodoxy’.

But second, I think it is an example of how economic input can substantially improve policy. And as I’ll show, economic frameworks can add rigour and prevent poor-quality spending.

So let me start with where we are.

The 2020s have seen industry policy come back into the spotlight across much of the Western world.

The IMF has documented more than 2500 new industrial policy measures - at least 1600 of which are ‘trade distorting’ - introduced across the world in 2023 alone. And looking just at direct subsidies to industry, advanced economies have been coming to the party with a vengeance since 2020.

And like all ideas that come back around, it comes with a new take on the original.

Current industry policy responds to real concerns about climate change and supply chain resilience, while also setting familiar goals such as job creation, industry competitiveness and regional economic development.

The role of economists in these debates is not to offer a reflexive ‘no’, but it is to ensure that there is rigour in the discussion of costs, benefits and trade-offs of any intervention.

Today, I think there are two principled justifications for intervention.

First is the green transition.

Most governments have accepted that to reduce the damage caused by climate change, we will need to reduce net emissions to zero by 2050 (or 2060 for some developing economies).

However, most do not have the full set of policies (including price signals) that we will need to get there.

The fact that markets do not yet fully price emissions means, in the absence of other supports, ‘green products’ – those associated with the transition like batteries and solar panels, or embodying renewable energy in production like green metals – will be undersupplied. And while markets are forward-looking, the lack of a credible emissions price pathway means the signals are not there for the investments the world will need to reach net zero goals.

The second justification is about managing geo-political risks.

A concern is that the concentration of key supply chains leaves countries exposed to risks from disruptions across a range of products.

The costs of diversifying these supply chains can be thought of as a form of insurance against these risks.

Of course this isn’t a single country’s problem to solve. And as large economies like the US take steps to diversify, Australia will benefit.

However, it is unlikely that Australia can simply free-ride on the costly efforts of others, and no doubt there will be pressure on us to ‘do our bit’ by seeking to diversify those supply chains where we have an obvious advantage. Critical minerals, where we have large endowments, is a frequently cited as an example.

These are, I think, the most robust arguments for government intervention. But they aren’t blank cheques for support.

Industry assistance comes with costs. These include direct costs (spending taxpayers’ money) and the diversion of workforce and resources from other activities.

There are also dynamic costs – even the promise of money on the table will see a raft of firms and lobby groups spend time and resources pushing for taxpayer support. And once the taps are on they can be hard to turn off.

The likely benefits of supports need to be weighed against the costs. But this is what economists do best: identifying and grappling with trade-offs.

The National Interest Framework developed by Treasury to assess Future Made in Australia investments is a great example of applying economic frameworks in this way.

The fact that the framework is written into the Future Made in Australia Bill and Treasury has been resourced to undertake sector assessments suggests the government recognises and values the discipline that economic frameworks can bring to these issues.

Industry assistance would almost certainly end up larger and less disciplined without this type of framework.

Economics is evolving

If you accept the premise that economics can and should have an ongoing role in solving major policy problems, the next question is, how well placed are we to do so?

Here I want to unpack what I think is the good news: that we increasingly have the tools and approaches to play a constructive role.

Better data

I suspect any of our historical policy luminaries would be floored if they could see the data a junior policy officer can access today.

The ABS has developed new administrative datasets using linked data from the census and commonwealth departments like Social Services, Education, Health and Aged Care and the ATO. The datasets - PLIDA and BLADE – give researchers an incredibly rich view of the economic activities of people and businesses.

Along with these, we have the Melbourne Institute’s longitudinal HILDA data – the faithful workhorse of many an economic research project in Australia – which has been surveying the same households and individuals to track changes in their economic and social outcomes for the past 22 years.

The breadth and depth of this micro and survey data opens the door to understand more about Australia.

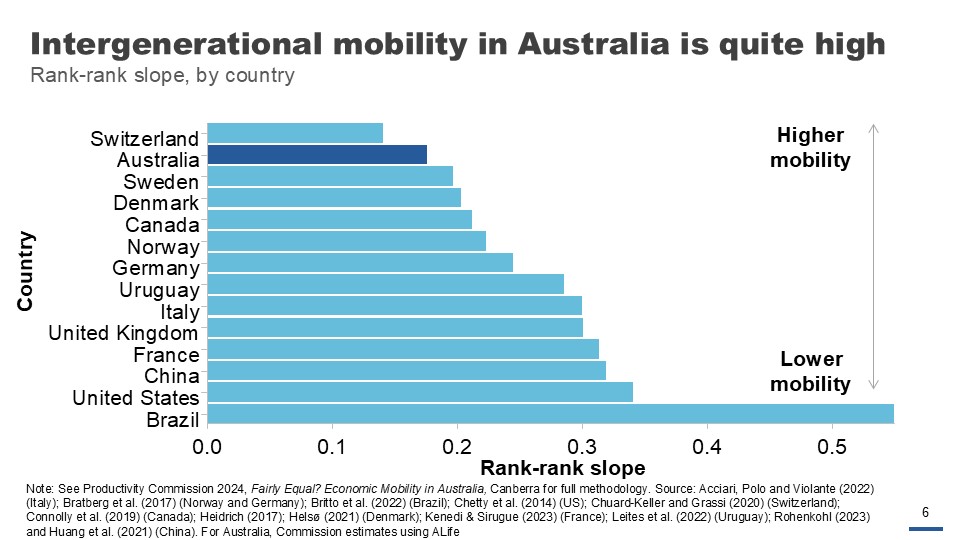

For example, PC researchers recently used the ATO’s Alife dataset to better understand economic mobility: how our economic outcomes are tied to those of our parents.

The results were a positive surprise: we found that two-thirds of today’s 40-somethings earn more than their parents did at the same age.

We also found a high level of relative income mobility – that is, children’s place in the earnings distribution were only loosely tethered to that of their parents. Comparing to international results on this measure, we are the second highest in the developed world (nice to beat out the Scandinavians for once).

This was something we just could not have got a clear picture of a decade ago.

Indeed, prior to this type of data, the best evidence of Australia’s economic mobility came from a study by economist turned parliamentarian Andrew Leigh alongside co-authors Gregory Clark and Mike Pottenger. They identified rare surnames amongst university graduates from 1870 and found that nearly 150 years later, people with those same surnames were more likely to be in the so-called ‘elite’ professions than people with surnames such as Smith. 8

No doubt this and other ‘status persistence’ of surnames studies reflect the ingenuity of economists in the face of data constraints, but increasingly the availability of admin data means we can go direct to the answer.

Even more importantly, the depth of the data that’s available is helping government agencies set and design policy.

There are many great examples of using administrative data in policy development. I particularly want to acknowledge the excellent work being done by the data analytics team within the Treasury Competition Taskforce, often in collaboration with other researchers.

As a member of the Advisory Board I see how their work has been influential in many of the reforms.

For example, their work on company mergers using BLADE revealed many more mergers occurring than were visible to the ACCC, and that very large firms were responsible for a disproportionate share of acquisitions. This helped shape the Government’s reforms which will give the ACCC increased oversight of merger activities.

On non-compete clauses, the team and others at the e61 Institute have shown that heavy use of these clauses is associated with lower wages by firms and longer spells of unemployment for workers.

And on aviation competition - this time using private sector microdata - they’ve quantified a 5-10% sustained reduction in airfares for each additional carrier on a route.

In the spirit of competitive federalism, I also want to point to the NSW Government’s new investment approach to human services.

Over the past 6 years, the NSW government has built a dataset that connects state human services data to Commonwealth administrative data sets, overcoming the tyranny of the federal-state data walls.

The result is extremely powerful.

The data now includes de-identified information from NSW child protection services, the justice system, Centrelink, the health system, and other government services. 9

The government is currently using it to evaluate the effectiveness of its child protection interventions.

For the first time, the department that manages child protective services can identify the state’s most vulnerable cohorts, design interventions to help them, and test whether the interventions are actually working.

This approach is also a wonderful example of how the use of administrative data can dovetail with another important development: a sharper focus on policy evaluation.

A stronger focus on evaluation

Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities and Treasury Andrew Leigh has named data and evaluation as a ‘match made in policy heaven’. 10

One for the true nerds perhaps but at its heart lies an important point.

We’ve known for a long time randomised controlled trials are the ‘gold standard’ for policy evaluation.

But costs, timeframes, and I expect some degree of cultural reluctance, has left them thin on the ground in Australia.

In May last year, the government announced it was setting aside funding to establish an Australian Centre for Evaluation.

‘ACE’, as it’s affectionately called in the Treasury portfolio, will be responsible for putting evaluation at the heart of policy development at the federal level.

It will assist the Commonwealth to run randomised controlled trials and policy evaluations. Not just on a large scale, but through quick and economical experiments. 11

These are increasingly feasible because in many cases we are already collecting the data needed for evaluation, taking the cost of the trial closer to the cost of the intervention itself. 12

Most importantly, evaluation gives decision makers better evidence to act on.

It can strengthen the case for effective programs but also allows us to save money on programs that don’t work: critically important in complex social policy areas where effective scalable interventions are notoriously elusive.

Assistant Minister Leigh gives the example of a UK program focussed on putting social workers in schools. It was a program popular with teachers, parents, students and - perhaps not surprisingly - social workers. However, after a two-year randomised trial across 300 schools, researchers at Cardiff and Oxford Universities found no positive impact. The program, previously intended to roll out across the nation was scrapped, saving taxpayers around £1 billion a year - or enough to pay for the UK Behavioural Insights Team that generated it for the next 100 years. 13

Now that’s a cost-benefit that everyone should get behind!

But while policy may be ‘late to the party’ compared to areas like medicine when it comes to taking the steps needed for proper evaluation – the growing embrace of it in the heart of government is a welcome development.

Talking with others

Historically, many economists have been sceptical of the value of qualitative evidence, or as human beings put it – ‘talking to people’ – in conducting their work. ‘The plural of anecdote is data’ was a common refrain when I was starting my career.

But increasingly it is recognised that consultation leads to a richer understanding of what is going on in the economy or in particular markets. And it is crucial for understanding the real-world impacts of policy.

More and more we see our major policy and economic institutions lean into talking with others.

A great example is Treasury’s work with the Department of Social Services targeting entrenched disadvantage in Australian communities.

As part of this work, Secretary Steven Kennedy recently explained how Treasury officials travelled to Burnie, Central Australia, Logan and Mildura as part of developing initiatives, including understanding how people in those communities wanted to access local data. 14

Working with a range of agencies, Treasury are now using these insights to improve the accessibility and use of Commonwealth data to assist those who are working to achieve better local outcomes.

As Dr Kennedy said, engaging with people generates qualitative insights that can complement the analysis of the hard data.

The Reserve Bank, too, has put a lot of effort into getting more out of what would once have been derided as a mere collection of anecdotes.

The RBA has used its business liaison program for over two decades to glean insights into the state of the economy beyond the story told by the statistics.

The program’s entire dataset includes about 20 million words from firms on economic conditions, and about 150,000 staff scores relating to key variables based on companies’ responses.

Now the RBA is using artificial intelligence to better mine the trove of information generated through the liaison program.

The Productivity Commission has always embraced consultation as an essential part of its policy process. But we are continuing to evolve how we do that.

Improving our consultation with Indigenous communities – emphasising transparency and reciprocity – has been crucial to the success of our review on the Closing the Gap Agreement. In the report’s forward, we called on government decision-makers to and acknowledge they do not know what’s best for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – or risk the Agreement failing.

We’re incorporating the lessons from the Closing the Gap review across our organisation – rolling out better engagement processes for our other policy work, and looking for new ways to unlock the value of talking to people in our research.

We are also working to bring in the voices of individuals or others who might not typically participate in a policy process. This has ranged from making it easy for people to provide ‘brief comments’ on our reviews through our website, 15 to a recent consultation session with 4-year-olds as part of our Early Learning and Care inquiry.

Turns out kids have a surprising breadth and depth of opinions if you ask!

Working with others

Economics as a discipline has always been considered somewhat insular – the ‘lonely island’ – of the social sciences.

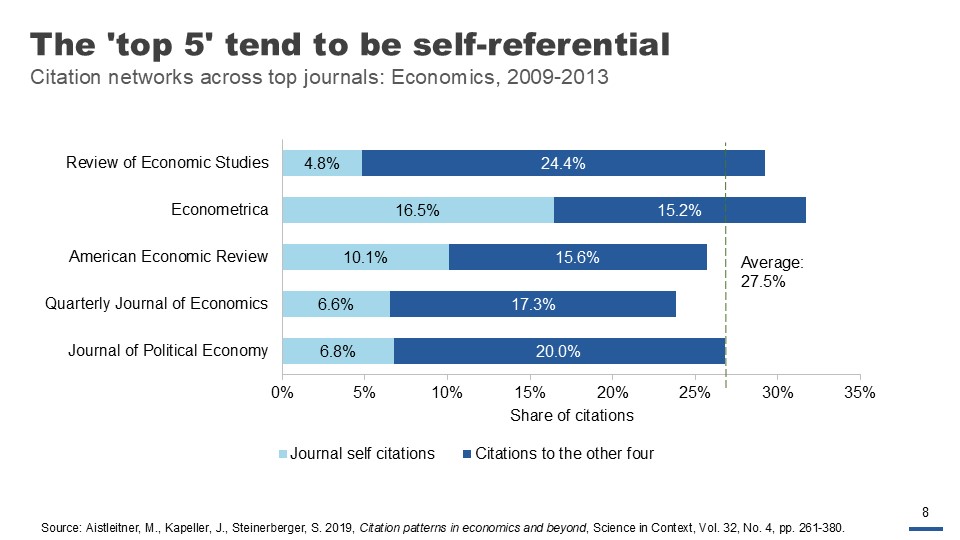

A 2013 study from Jerry Jacobs 16 – ironically a defender of disciplinary boundaries – has been used to critique economics as being almost entirely self-referential. His work identified that 81% of economics citations are of other economics papers, compared to 52% for sociology, 53% for anthropology and 59% for political science.

And that’s before you get to the ‘island within the island’.

More than one quarter of the citations in the top 5 economics journals are to other papers in the same 5 journals, compared to between 8% and 12% for leading journals in psychology, sociology, political science, and physics. 17

But more recent work shows this is changing. Economics has increased its citations of other social sciences and business disciplines.

It has also embraced new sub-branches that embed other disciplines like behavioural economics – the happy fusion of economics and psychology.

On the ground in policy land, my own organisation has gone from exclusively hiring graduates with an honours degree in economics to bringing in those with degrees in PPE, cultural studies, and psychology.

I understand we aren’t alone in casting our nets more broadly, with many other economic agencies similarly focused on recruiting from outside the usual pool.

Working with people with different frameworks requires more mental work to test and integrate these alternative perspectives. But studies suggest that while diverse teams feel less comfortable (and therefore people can assume they are performing worse), they perform objectively better overall at problem solving. 18

I think the same will be true for complex policy problems, even if it’s harder to test in a lab.

So I encourage you all to embrace the discomfort that can sometimes emerge - it seems a low price to pay for more robust work.

But economics must continue to evolve

Lest we lapse into a bit too much self-congratulation, there are still important areas where economists must step up if we are to remain relevant in a complex policy-making environment.

Getting our hands dirty

Some economists are in their happy place when weighing in on policy debates from a point of high theory.

But while theory will always be important, theory alone is less likely to provide the right answer to some of the complex issues that policy makers grapple with today.

- To provide advice on fraught issues like water allocation in the Murray Darling Basin we have to understand complex systems and their interactions and feedback loops.

- When advising on Indigenous policy, we have to grapple with the importance of culture, connection to country, and the scars of history.

- To make recommendations on school education we need to consider how policy will jump from departmental edict to the behaviours of thousands of teachers on the ground.

- To input into climate policy, we often must grapple with ‘second-best’ (or third or fourth best) policy levers, recognising that ‘first best’ may simply not be politically feasible.

And in all areas, we must have an eye to the less sexy but always important question of implementation. The cleverest policy idea will only be the best one if it can actually be put into practice.

I’ve always thought that policy advice done well is a somewhat chaotic (but tasty) buffet of theory, history, deep sectoral understanding, empirical analysis, served with a generous side of humility.

The best buffet cooks approach problems with strong frameworks but a voracious appetite for information and an openness to be ‘surprised’ by what they find.

Communication matters

The capacity of economists to influence policy makers and public debates will depend on the clarity with which we express our ideas.

I’m going to lapse dangerously into generalisation here and say we haven’t always been as good at this as we could be.

Of course, economists are not the only public servants that slip into ‘bureaucratese’ – a kind of passive word soup – to avoid committing to a point, nor the only academics that hide behind complex language and technical jargon.

But I think economists have a particular obligation to speak directly and plainly.

If we stake our claim to our unique contribution to public policy being the clarity of our thinking, that clarity must be evident in the advice we provide.

Further, given the importance and complexity of the issues that we provide advice on, the stakes for communication are high.

This is something I have thought a lot about since becoming Chair of the Productivity Commission, an organisation well-known for high quality policy research packaged in 600-page reports!

The length of the products in part reflects the very broad terms of reference we receive from government and the huge amount of research that sits behind our policy recommendations. However, we are working to ensure that we write our reports as clearly and economically as possible. For us this has meant investing in serious editing capacity, skilling our staff and making it a priority in our work.

To butcher Mark Twain, it takes longer to write a short report than a long one, and so we are committing to spend the time to make sure that our reports are as direct and easy to follow as possible.

I’m happy to use you all as my commitment device, but to me the real incentive is giving our work the best possible chance of influencing policy.

Watching the pipeline

If the nature and scale of the policy problems confronting us have become ever more complicated, then we as a country will need our future brightest minds bent to the task of solving them.

Unfortunately, the pipeline of tomorrow’s star economists is worryingly narrow.

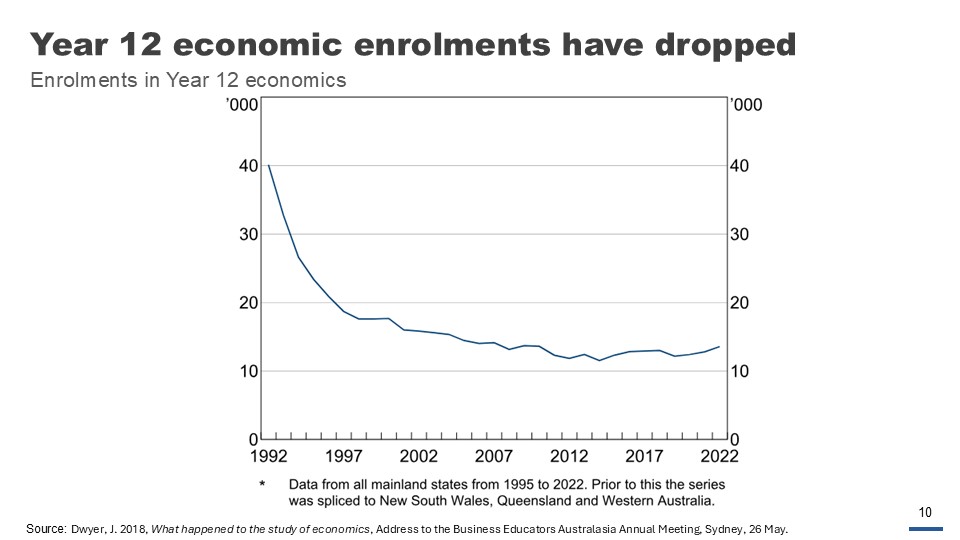

As the RBA’s Jacqui Dwyer has noted, the number and diversity of young Australians studying economics in school has dwindled to a trickle.

Year 12 enrolments in economics are 70 per cent lower than in the early 1990s – with most of the decline happening through that decade. This century it has flatlined.

Students don’t get the lofty ambitions of economics – or how it can be used for the good of society. An RBA survey revealed students see it as both more boring and more difficult than business studies. Not a great mix!

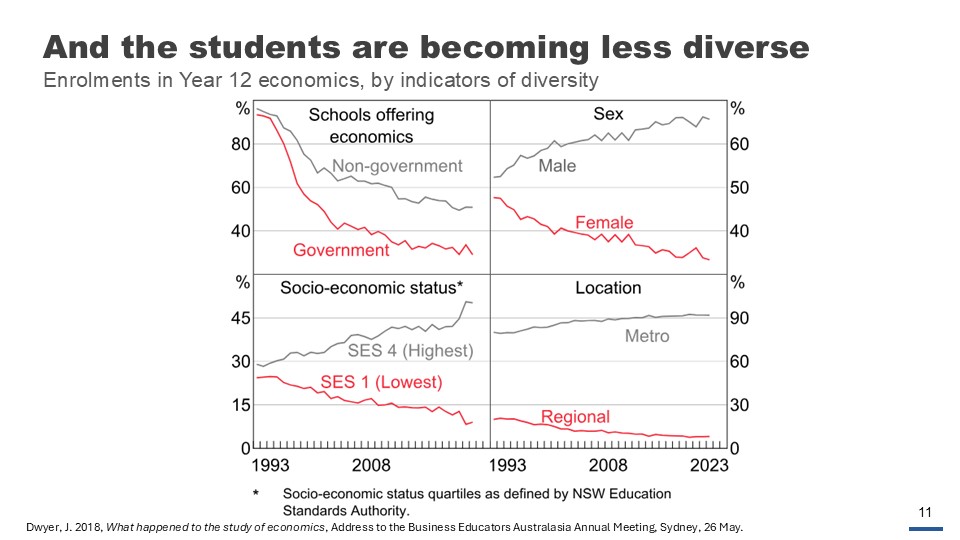

And while interest in studying economics has dropped overall, the number of female economics students have disappeared at an even faster pace.

Since the early 1990s, the gender split has gone from fifty-fifty, to male students now outnumbering females two to one.

What’s more, the drop in economics students has been even more pronounced in government schools which are more likely to be co-educational, and which accept kids from all socio-economic backgrounds.

This has contributed to this drop in female participation, and it has also left a smaller share of students from poorer backgrounds.

As Jacqui said: “Exclusivity is becoming a hallmark of economics and yet a robust and inclusive discipline can raise economic literacy, shape the future of economic thought and practice, and improve the quality of both public discourse and public policy”.

The declining interest in economics in our schools also risks a weaker community-wide understanding of key economic concepts. This could make the difficult trade-offs discussed earlier even harder to reach consensus on.

Our economic institutions must also evolve

I have focussed my remarks so far on the role of economists and the economics profession, but a huge part of the strong contribution made by economics to Australian policy has been grounded in our institutions.

The Australian Treasury and other public service agencies have a long and proud history of advising governments on policy reform. And delivery of key aspects of policy has been overseen by independent institutions - like the Reserve Bank, ACCC, APRA, ASIC and the ATO - that operate at arm’s length from the political process.

Our institutions haven’t always been perfect, but they have been rightly ascribed as playing a critical role in Australia’s strong economic performance over many decades. 19

My organisation, the Productivity Commission, is relatively unique by global standards – operating independently of government but advising it across a broad range of policy areas. Some of our states also have equivalents – but with some variation in the degree of independence.

But our institutions like the rest of our profession can and should evolve to meet modern challenges, while not compromising on their core values.

Treasurer Jim Chalmers is reviewing key economic institutions in Australia.

I call it the ‘Jim Chalmers day spa’ because of the focus on being ‘refreshed’ and ‘revitalised’. The Productivity Commission has been in the day spa alongside the RBA and now ASIC.

The RBA has already changed to fewer and longer board meetings and live press conferences in response to an independent review that raised some areas for improvement in terms of board structure and dynamics, communication, internal culture and governance. 20 More substantive changes to its governance structure – including a specialist monetary policy board – have not made it through the parliament. Not all day spa procedures are painless!

The PC’s review process was less formal but has informed new guidance provided by a Statement of Expectations.

The Statement focuses on the need for the PC to provide practical advice, draw on diverse frameworks, use cutting-edge data analysis and improve our communications.

We have welcomed and embraced those directions. Importantly the Statement recognises and maintains the things that have made the PC an important and unique institution – our independence, our rigour, our broad remit and our national interest lens in evaluating policy.

Some have suggested that even receiving such a statement risks compromising the PC’s independence. I disagree. Our independence has always been about saying what we believe without fear or favour – nothing changes on that front. But no institution is above being evaluated and we have been clear we intend to take on board the areas the government has identified for improvement.

Australia’s institutions are an important national asset – our capacity to evolve and move with changes in the policy environment are crucial to the ongoing influence of the economics profession on policy.

A big ambition

Let me finish on an optimistic note. Economics can and should play an important role in Australian policy making for decades to come.

The ‘wicked problems’ that bedevil us – from housing affordability to the clean energy transition – can’t be solved without the expertise and tools that economics provides.

Trust in the economics profession may be at a low ebb, but the best response is not to withdraw and put up our walls.

It’s to be more open-minded, as people and institutions: to new ideas, new disciplines, new data, and new approaches.

At the same time, economic policy makers must be prepared to champion the type of rigorous decision making that underpinned best of what’s come before us.

We’ll do that by doing what we do best: building the evidence base and acknowledging and weighing trade-offs.

We already have concrete examples of this, whether it’s the establishment of the Australian Centre for Evaluation in Treasury, or the development of a National Interest Framework that will guide the Future Made in Australia program.

The Productivity Commission is doing its bit to both move with the times, and maintain its focus on rigorous and independent research.

Our goal is like all of yours: to help solve the problems, big and small, that can help contribute to a new era of sustainable prosperity for all Australians.

Sometimes that will involve saying unpopular things that need to be said.

Other times it may involve a dose of humility including admitting that economics does not hold all the answers.

And as much as some things change, others don’t.

The next chapter of Australia’s economic policy legacy is in your hands.

Footnotes

- Productivity Commission 2003, From industry assistance to productivity: 30 years of ‘the Commission’, Productivity Commission, Canberra. Return to text

- Dwyer, J. 2018, What happened to the study of economics, Address to the Business Educators Australasia Annual Meeting, Sydney, 26 May. Return to text

- The Hon Gareth Evans AC KC FASSA FAIIA 2015, The seven larger than life Australian Public Service dwarfs, book launch of Furphey, S. (ed) 2015, The seven dwarfs and the age of the mandarins: Australian Government administration in the post-war reconstructionist era, ANU Press, Canberra, 17 December. Return to text

- Ostry, J.D., Loungani, P. & Furceri, D. 2016, Neoliberalism: Oversold?, Finance and Development, IMF, June, Vol. 53, No. 2; Stiglitz, J. 2017, Globalisation and its discontents revisited, Penguin Press. Stiglitz, Globalisation and its Discontents. Return to text

- Deaton, A. 2024, Rethinking my economics, IMF, Finance and Development Magazine, March. Return to text

- The Treasurer the Hon Dr Jim Chalmers MP 2024, Building a new economy on 5 pillars of productivity address to the Australian business economists, Address to the Australian Business Economists, 13 November, Sydney. Return to text

- Yglesias, M. 2024, Neoliberalism and its enemies, part III, Slow Boring, August 7. Return to text

- The authors define a set of elite ‘rare’ surnames in 1900 as those surnames where 29 or fewer people held the name in Australia in 2014 in the voting roll, and where someone holding that name graduated from Melbourne or Sydney universities 1870-1899. Clark, G, Leigh, A, and Pottenger, M 2020, Frontiers of mobility: Was Australia 1870–2017 a more socially mobile society than England?, Explorations in Economic History, Vol. 76. Return to text

- Department of Communities and Justice NSW 2024, Human Services Dataset (HSDS), NSW Government: https://dcj.nsw.gov.au/about-us/facsiar/human-services-dataset-hsds.html. Return to text

- The Hon Dr Andrew Leigh MP 2023, Data and evaluation: A match made in policy heaven, Speech to the Data for Policy Summit organised by the Life Course Centre, 15 August, Canberra. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- The Hon Dr Andrew Leigh MP 2023, Evaluating policy impact: Working out what works, Speech to the National Press Club, 29 August, Canberra. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Kennedy, S. 2024, Evidence informed policy making, Address to the University of Adelaide, South Australian Centre for Economic Studies Corporate Members Luncheon, 30 August, Adelaide. Return to text

- More than 1,650 comments were provided in 2023-24 alone. Productivity Commission 2024, Annual report 2023-24, Annual report series, Canberra. Return to text

- Jacobs, J. A. 2013, In Defence of Disciplines: Interdisciplinarity and Specialization in the Research University, University of Chicago Press, cited in Fourcade, M., Ollion, E. & Algan, Y. 2015, The superiority of economists, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 29, No. 1, Winter, pp. 89-114. Return to text

- Aistleitner, M., Kapeller, J., Steinerberger, S. 2019, Citation patterns in economics and beyond, Science in Context, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 261-380. Return to text

- Rock, D., Grant, H. & Grey, J. 2016, Diverse teams feel less comfortable – and that’s why they perform better, Harvard Business Review, September 22. Return to text

- McLean, I. W. 2012, Why Australia prospered: The shifting sources of economic growth, Princeton University Press. Return to text

- Review of the Reserve Bank of Australia 2023, An RBA fit for the future, Australian Government, Canberra. Return to text