Report on Government Services 2026

PART C, SECTION 7: RELEASED ON 3 FEBRUARY 2026

7 Courts

This section reports on the performance of court administration functions of Australian and state and territory courts.

Data is reported for the Federal Court of Australia, the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (FCFCOA) (Division 1), FCFCOA (Division 2), the criminal and civil jurisdictions of the supreme courts (including probate registries), district/county courts, magistrates' courts (including children's courts), coroners' courts and the Family Court of Western Australia.

The Indicator results tab uses data from the data tables to provide information on the performance for each indicator in the Indicator framework. The same data is also available in CSV format.

Data downloads

Refer to the corresponding table number in the data tables for detailed definitions, caveats, footnotes and data source(s).

Context

Objectives for courts

Courts aim to safeguard and maintain the rule of law and ensure equal justice for all. Court services support the courts and aim to encourage public confidence and trust in the courts by enabling them to:

- be open and accessible

- be affordable

- process matters in a high quality, expeditious and timely manner.

Governments aim for court services to meet these objectives in an equitable and efficient manner.

The primary support functions of court administration services are to:

- manage court facilities and staff, including buildings, security and ancillary services such as registries, libraries and transcription services

- provide case management services, including client information, scheduling and case flow management

- enforce court orders through the sheriff’s department or a similar mechanism.

Court support services are reported for the state and territory supreme, district/county and magistrates’ (including children’s) courts, coroners’ courts and probate registries, and for the Federal Court of Australia, the FCFCOA (Divisions 1 and 2), and the Family Court of Western Australia.

The High Court of Australia, tribunals and specialist jurisdiction courts (for example, Indigenous courts, circle sentencing courts, drug courts and electronic infringement and enforcement systems) are excluded from this report.

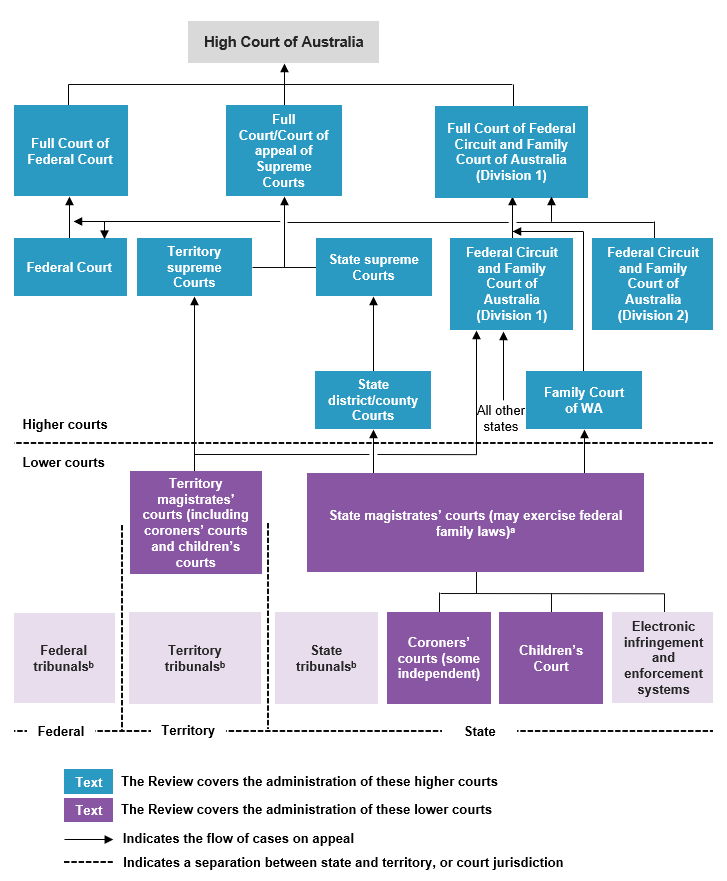

There is a hierarchy of courts within each state and territory (figure 7.1). Differences in state and territory court levels mean that the allocation of cases to courts and seriousness of cases heard varies across jurisdictions. For most states and territories, the hierarchy of courts is as outlined below:

- Supreme courts (includes probate)

- District/county courts

- Magistrates’ courts (includes children’s and coroners’ courts).

Supreme Courts

In civil matters, Supreme courts deal with appeals and probate applications and have an unlimited jurisdiction on claims. In criminal matters, Supreme courts hear appeal cases and handle the most serious criminal cases.

In all states and territories, probate issues are heard in Supreme courts.

District/County Courts

The District/county courts have jurisdiction over indictable criminal matters, but differences exist among the states that have a District/county court. In civil matters, all District/county courts hear appeals and deal with differing amounts of financial claim values among the jurisdictions. District/county courts do not operate in Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory, instead the supreme courts generally exercise a jurisdiction equal to that of both the Supreme and District/county courts in other states.

Magistrates’ Courts

Magistrates’ courts handle summary cases and some indictable offences with different specifications for the cases heard across jurisdictions. For civil matters, the claim limit and type of cases these courts handle vary across jurisdictions.

Children’s Courts

Children's courts are specialist jurisdiction courts which may sit within Magistrates' courts. Depending on the state or territory legislation, children's courts may hear both criminal and civil matters.

Coroners’ Courts

In all states and territories, Coroners' courts (which generally operate under the auspices of state and territory Magistrates' courts) inquire into the cause of sudden and/or unexpected reported deaths. All coronial jurisdictions investigate deaths in accordance with their respective Coroners Act.

Australian court levels

Australian courts hear and determine civil matters arising under laws made by the Australian Government. The hierarchy of Australian courts (refer to figure 7.1) is as follows:

- the High Court of Australia

- the Federal Court

- the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1)

- the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2).

Figure 7.1 Major relationships of courts in Australia a

a In some jurisdictions, appeals from lower courts or District/county courts may go directly to the full court or court of appeal at the Supreme/Federal level; appeals from the Federal Circuit Court can also be heard by a single judge exercising the Federal/Family Courts’ appellate jurisdiction. b Appeals from federal, state and territory tribunals may go to any higher court in their jurisdiction.

Australian Government courts

On 1 September 2021, the Family Court of Australia and Federal Circuit Court of Australia were renamed as the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1) (FCFCOA (Division 1)) and the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) (FCFCOA (Division 2)) respectively.

Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court has jurisdiction to hear and determine any civil matter arising under laws made by the Federal Parliament, as well as any matter arising under the Constitution or involving its interpretation.

The Federal Court has a substantial and diverse appellate jurisdiction. Non‑appeal matters for the Federal Court include a significant number of Native Title matters. The Federal Court has the power to exercise indictable criminal jurisdiction for serious cartel offences and a very small summary criminal jurisdiction.

Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 1)

The FCFCOA (Division 1) has first instance jurisdiction in all states and territories except Western Australia. It has jurisdiction to deal with matrimonial cases and associated responsibilities including divorce proceedings, financial issues and children’s matters such as who the children will live with, spend time with and communicate with, as well as other specific issues relating to parental responsibilities. It can also deal with ex-nuptial cases involving children’s matters. The most complex disputes are heard in the FCFCOA (Division 1). The FCFCOA (Division 1) has appellate jurisdiction and hears all family law appeals from the FCFCOA (Division 1), FCFCOA (Division 2), the Family Court of Western Australia, and other state and territory courts exercising original jurisdiction in family law.

Family Court of Western Australia

The Family Court of Western Australia was established in 1976 as a state court exercising both state and federal jurisdiction. The Court deals primarily with disputes arising out of relationship breakdowns. It comprises judges, family law magistrates and registrars.

Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2)

Since 1 September 2021, the FCFCOA (Division 2) is the single point of entry for all family law applications filed in the federal family law courts. As a result, most family law applications continue to be case managed and heard in the FCFCOA (Division 2). The Court now also undertakes a triage function to ensure the most legally and/or factually complex cases are transferred to the FCFCOA (Division 1) for hearing.

The jurisdiction of the FCFCOA (Division 2) is broad and includes a number of varied and complex areas including family law and child support, administrative law, admiralty, bankruptcy, copyright, consumer law, human rights, industrial and employment law, migration, privacy and trade practices.

More information

Detailed information on the operation of Australian, state and territory court systems, is presented in the explanatory material section.

Nationally in 2024-25, total recurrent expenditure (excluding payroll tax) by Australian, state and territory courts in this report was approximately $2.77 billion (table 7.1). Expenditure in some states and territories is apportioned (estimated) between the criminal and civil jurisdictions of courts so caution should be used when comparing criminal and civil expenditure across states and territories.

Total recurrent expenditure less court income (excluding payroll tax) for the Australian, state and territory courts in this report was $2.24 billion in 2024-25 (tables 7A.14−15). Court income is derived from court fees, library revenue, court reporting revenue, sheriff and bailiff revenue, probate revenue, mediation revenue, rental income and any other sources of revenue (excluding fines). The civil jurisdiction of courts accounts for the vast majority of income received (table 7A.13).

Cost recovery and fee relief in the civil courts

Court fees are mainly collected in civil courts and in some jurisdictions are set by government rather than court administrators. The level of cost recovery from the collection of civil court fees varies across court levels and states and territories. Nationally, in 2024-25, 29.6% of costs were recovered through court fees in the Supreme courts (excluding probate), 20.6% in the Federal court, 42.6% in the District courts and 20.2% in the Magistrates’ courts (excluding children's courts) (table 7A.16). Cost recovery tends to be low in the children’s courts – in these courts many applications do not attract a fee.

Most courts in Australia are able to waive or reduce court fees to ameliorate the impact on vulnerable or financially disadvantaged parties (fee relief). Table 7.2 shows that the proportions of total payable civil court fees which were waived or reduced in 2024-25 were highest in the Northern Territory Magistrates' court (48.1%) followed by the FCFCOA (Division 2) (40.5%) and the Family Court of Western Australia (20.1%).

Fee exemptions are also available in some courts – this is usually where legislation exists to exempt particular categories of fees from being payable. Fee exemptions are more common in the Federal courts than state and territory courts (table 7A.19).

During 2024-25, almost $55.6 million of civil court fees were either waived, reduced or exempted and therefore not recovered by courts (table 7A.19).

Staffing

Descriptive information on the numbers of judicial officers and full time equivalent staff can be found in tables 7A.28–30.

Lodgments

Lodgments are matters initiated in the court system and provide the basis for court workload as well as reflecting community demand for court services (refer to tables 7A.1–2 for further information).

State and territory courts

Nationally, there were 750,028 criminal lodgments registered in the supreme, district/county, magistrates’ and children’s courts in 2024-25 (table 7A.1). There was an increase in criminal lodgments from 2023-24 across all states and territories except Queensland.

Nationally, there were 404,652 civil lodgments. An additional 94,602 probate matters were lodged in the supreme courts (table 7A.2).

In the coroners’ courts, there were 30,011 deaths and 39 fires reported, with numbers varying across jurisdictions as a result of different reporting requirements (table 7A.2). There were an additional 14,136 lodgments in the Family Court of Western Australia.

There were more lodgments in the criminal courts than civil courts in all states and territories. Most criminal and civil matters in Australia in 2024-25 were lodged in magistrates’ courts (figure 7.2). The number of lodgments per 100,000 people can assist in understanding the comparative workload of a court in relation to the population of the state or territory (refer to tables 7A.3 (criminal) and 7A.4 (civil) for data by state and territory).

Australian Government courts

In 2024-25, there were 5,515 lodgments in the Federal Court of Australia, 11,369 lodgments in the FCFCOA (Division 2, non-family law matters) and 101,511 lodgments in the FCFCOA (Divisions 1 and 2, family law matters) (table 7A.2).

Finalisations

Finalisations represent the completion of matters in the court system so that they cease to be an item of work for the court. Each lodgment can be finalised only once. Matters may be finalised by adjudication, transfer, or another non‑adjudicated method (such as withdrawal of a matter by the prosecution or settlement by the parties involved)1.

Most cases that are finalised in the criminal and civil courts do not proceed to trial. Generally, cases that proceed to trial are more time-consuming and resource-intensive. In the criminal courts the proportions of all finalised non‑appeal cases that were finalised following the commencement of a trial in 2024-25 varied from 4% to 72% in the supreme courts and from 7% to 20% in the district courts. Proportions in the magistrates' courts varied from 1% to 20% (State and territory court authorities and departments, unpublished).

State and territory courts

In 2024-25, there were 725,538 criminal finalisations in the supreme, district/county, magistrates’ and children’s courts and 399,280 civil finalisations in these courts (tables 7A.5–6).

There were an additional 30,660 cases finalised in the coroners’ courts and 14,282 cases finalised in the Western Australian Family Court (table 7A.6). The number of finalisations per 100,000 people is available in tables 7A.7–8.

The pattern of finalisations across states and territories (figure 7.3) is similar to that of lodgments, but the number of lodgments will not equal the number of finalisations in any given year because not all matters lodged in one year will be finalised in the same year.

Australian Government courts

In 2024-25, there were 4,722 cases finalised in the Federal Court of Australia, 101,520 cases finalised in the FCFCOA (Division 1 and Division 2, family law matters) and 10,030 cases finalised in the FCFCOA (Division 2, non-family law matters) (table 7A.6).

Lodgments and finalisations in criminal courts – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

The proportion of all criminal non-appeal matters lodged and finalised in the Supreme, District, Magistrates’, and Children’s courts involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander defendants show that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are overrepresented in the criminal courts relative to their representation in the community (table 7.3). Indigenous status is based on self-identification by the individual who comes into contact with police, with this information transferred from police systems to the courts when the defendant’s matter is lodged in the courts. Data for criminal courts are presented for six jurisdictions (New South Wales (data is available for the Supreme Court only), Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory). For other jurisdictions, data on Indigenous status is either not available or not currently considered to be of sufficient quality for publication.

Finalisations in civil courts – applications for domestic and family violence protection orders

Domestic and family violence matters2 are generally dealt with at the magistrates’ court level. Applications for protection orders are civil matters in the court while offences relating to domestic and family violence (including breaches of violence orders and protection orders) are dealt with in criminal courts. Protection orders are the most broadly used justice response mechanism for addressing the safety of women and children exposed to domestic and family violence (Taylor et al. 2015).

In 2024-25, across all magistrates’ courts 41.9% of all finalised civil cases involved applications for domestic or family violence-related protection orders (excludes interim orders and applications for extension, revocation or variation) (table 7.4). Proportions varied across states and territories but remained unchanged nationally compared with 2023-24 (table 7A.10).

The FCFCOA (Division 1) and FCFCOA (Division 2) do not issue family violence protection orders. Since 1 November 2020, it has been mandatory in both courts for each party to file a Notice of Child Abuse, Family Violence or Risk in every proceeding where parenting orders are sought. In 2024-25, data from the Notices filed with applications for final orders seeking parenting orders indicates that in 86% of matters, one or more parties alleged that they had experienced family violence (Commonwealth of Australia 2025).

- For the purposes of this report, civil non-appeal lodgments that have had no court action in the past 12 months are counted (deemed) as finalised. The rationale for this is to focus on those matters that are active and part of a workload that the courts can progress. A case which is deemed finalised is considered closed – in the event that it becomes active again in the court after 12 months it is not counted again in this report. Locate Footnote 1 above

- While ‘domestic’ and ‘family’ violence are distinct concepts, the former referring to violence against an intimate partner and the latter referring to broader family and kinship relationships, the terms are often used interchangeably and their definitions generally incorporate both domestic and family-related violence. Locate Footnote 2 above

A PDF of Part C Justice can be downloaded from the Part C sector overview page.

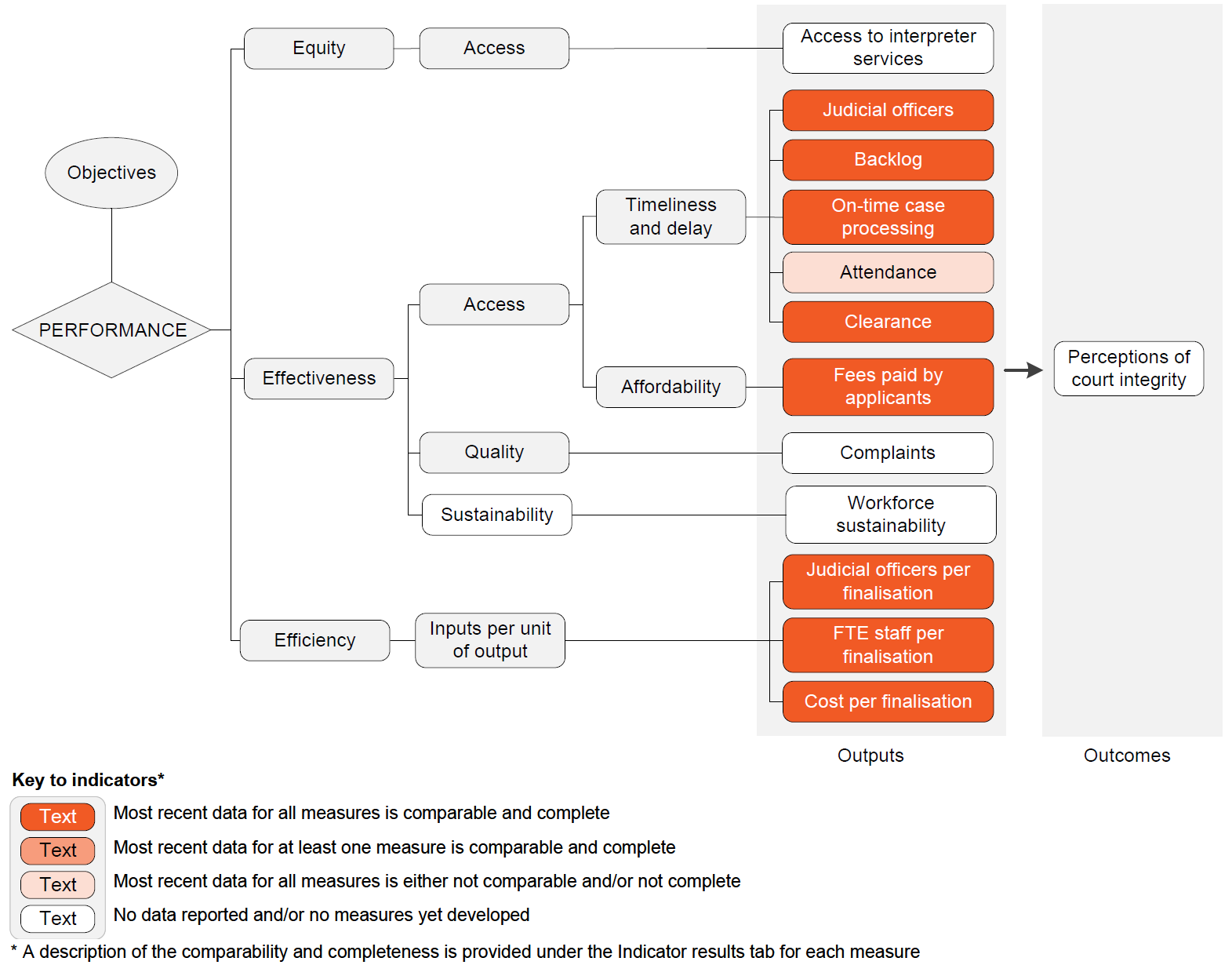

Figure 7.5 shows the proportion of finalised cases: