PC News - May 2017

How resilient are Australia's regional economies to the end of the mining boom?

The Australian economy's transition from the mining investment boom towards broader based growth is presenting both challenges and opportunities for Australia's regions.

Australia benefited substantially (and will continue to benefit) from the resources boom, which ended in about 2013. It led to higher incomes on average for individuals, larger profits for many companies engaged in mining, and increased revenues for State and Territory governments and the Australian Government. Mining employment remains substantially higher today than in 2008. However, the slowing of the investment phase has caused transitional pressures. The Australian Government asked the Productivity Commission to undertake a study of the impact on regional economies of the transition from the mining investment boom. The study is to examine how well different regions are adapting to the transition, and the factors influencing their capacity to successfully adapt to economic change. It will also identify those regions most at risk of failing to adjust to changing economic conditions.

The mining commodity and investment cycle was large

Western Australia

Economic growth peaked at 9.1 per cent in 2011-12 and business investment accounted for over 34 per cent of economic growth in 2012-13 (the average was about 12 per cent between 1989-90 and 2004-05). Following the end of the investment phase, economic growth slowed and in 2015-16 was the lowest in 13 years, at 1.9 per cent. The unemployment rate rose from about 3 per cent in 2008 to over 6 per cent in the year to February 2017.

Queensland

Construction expenditure in Queensland rose to unprecedented levels during the boom, peaking in 2013-14 at $36.6 billion, and subsequently decreasing by about 70 per cent. During the period 2008 to February 2017, the unemployment rate rose from less than 4 per cent to over 6 per cent.

The Commission released its initial report in April 2017, and is seeking submissions on the report by the end of July. Following consultation within regions, a final report will be sent to the Government in December 2017.

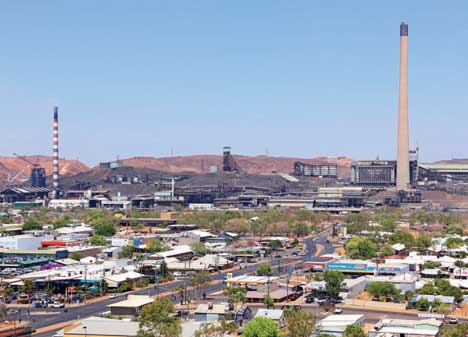

The Commission's study covers all regions of Australia (both urban and non-urban), not only those directly affected by mining investment (such as the Pilbara, the Surat and Bowen basins, and the Hunter Valley). Some regions are subject to transitional pressures from other sources, such as environmental, energy and climate change policies (examples include the Latrobe Valley and Port Augusta/Leigh Creek regions). Other regions are subject to economic and policy changes affecting specific industries (for example, vehicle manufacturing in Geelong and North Adelaide).

What is a region?

'Regions' can be defined in many ways, and the way that they are best defined is likely to depend on the purpose of the analysis. For example, the definition used in this study is likely to be different from the definition used in a study of the Murray-Darling Basin, where environmental issues regarding water are the main policy interest.

Within the context of this study, there is no clear answer as to how regions are best defined. 'Regions' could be based on economic characteristics (‘mining’ or ‘manufacturing’ regions), administrative units (such as local government areas), or the effects of the resources boom (for example, towns that are interrelated because of fly in, fly out workers).

Due to the widespread effect of the resources boom and the variability in the data across regions that might be considered similar, the Commission has used geographical regions defined under the ABS Australian Statistical Geography Standard.

Developing a framework to assess economic resilience and adaptation

The Commission adopted a framework comprising the following three key elements.

1. Economic performance over time

An examination of economic growth over time can identify regions that have experienced a significant disruptive event and recovered (were resilient), or stagnated or deteriorated (were non-resilient). This may provide insight into factors associated with resilience and appropriate policies for enhancing resilience and adaptive capability. In practice, operationalising this concept is challenging, given the time series data available and the level of regional disaggregation possible.

2. An economic metric of relative adaptive capacity

The Commission was asked to develop a single economic metric that can be used to rank and identify regions most at risk of failing to adjust successfully to economic disruptions.

This was achieved by creating an index of the relative adaptive capacity for each region, using data from the 2011 Census of Population and Housing. Factors used to construct the metric included skills, income, natural resources and access to infrastructure and services. Caution is required if making policy decisions based on the rankings of regions using the estimated metric of relative adaptive capacity in the initial report. There is unavoidable uncertainty about its estimated value for each region, and actual adaptation to any specific disruption would be affected by factors beyond the metric. Nevertheless, the metric can be used to explore some broad themes and patterns of adaptive capacity in Australia's regions.

3. Framework for economic and social development

The third element is a policy framework to assess the scope for economic and social development in regions, and the factors that may inhibit adaptation to changing circumstances. The framework is intended to provide guidance to governments about how best to support regional adaption and development.

A snapshot of regional growth and adaptive capacity

The study used the first two elements of the Commission's framework to assess the performance and adaptive capacity of Australia's regions. Initial findings include the following:

- Most regions (about 80 per cent) have experienced overall positive growth in employment over the past five years. However, almost all regions have displayed significant variability in growth rates.

- Not all regions have the same capacity to adapt to change. Regional communities likely to have the least capacity to adapt (about 12 per cent of all regions) are spread across all areas of Australia, in both remote and regional areas and in outer urban areas, including major cities (figure 1).

- Major cities and very remote areas have a relatively higher representation in the least adaptive category of regions. Over half of the people in the least adaptive regions reside in the greater metropolitan areas of Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide. Regions with the least adaptive capacity frequently have high levels of disadvantage.

- Regions whose economic base is large-scale mining have generally had the highest rates of growth in employment since 2005, notwithstanding the end of the investment boom. Overall, employment in mining remains higher now than it was prior to the boom. However, not all mining areas are prospering and some are in decline. These are typically areas that have marginally profitable mines or where existing mines are approaching the end of their economic lives (including coal mines supplying local power stations that have been closed).

- Regions based predominantly on manufacturing tend to have relatively low rates of growth in employment and lower adaptive capacity. In contrast, regions whose economies are predominantly based on services (cities, large regional centres) tend to have higher rates of growth.

- Regions that are predominantly based on agriculture, particularly broadacre cropping, tend to have lower rates of growth in employment. Improvements in agricultural productivity mean output can increase with fewer workers. Agricultural regions have also experienced consolidation of small towns into larger regional towns.

These patterns reflect longer-term trends in employment and the move away from manufacturing and agriculture towards services (a trend observed in other advanced economies) as well as resource industries. The extent to which regions are affected will therefore depend on their industry mix and the concentration of employment in particular sectors.

Figure 1: The adaptive capacity of Australia's regions

Data source: Commission estimates

Strategies for successful transition and development

The Commission's initial study finds that there is no single approach to facilitating adaptation and sustainable development in all regions. Moreover, it is unclear how successful current policies for facilitating adaptation and development have been, because evaluation is not usually undertaken.

Developing and implementing policies to support people in regional communities is a complex task for governments, and properly evaluated success is rare. There is no easy solution or 'one size fits all' approach that will facilitate transitioning and adaptive economies in all regions of Australia.

Nevertheless, it appears the best strategies are those that:

- remove barriers to people or business owners relocating, both within or to other regions

- are identified and led by the regional community itself, in partnership with all levels of government

- are aligned with the region's relative strengths and inherent advantages

- are supported by targeted investment in developing the capability of the people to deal with adjustment and the connectivity of the region to other regions and markets

- are designed with clear objectives and measureable performance indicators and subject to rigorous evaluation.

Transitioning Regional Economies

- Read the Initial Report released April 2017

- The Inquiry Report is due to be provided to the Australian Government by December 2017.