Our trade fortunes rely less on China than you think

7 September 2021

The stress test created by Beijing’s 2020 tariffs and bans reveals significant facts about the make-up and nature of Australia’s foreign trade.

Much has been written about Australia’s vulnerability to supply chain disruptions in essential and critical imports and our preparedness as a nation to respond to blockages in a manner that limits harm.

But what about our vulnerability to major disruptions in our exports?

The question became more than an academic one in May 2020 when China hit Australia with a series of punitive trade restrictions.

First, there were tariffs on barley. Then imports from four beef abattoirs were suspended. By October, the sight of Australian coal ships moored outside Chinese ports, unable to unload, prompted questions about the impacts on the wider Australian economy and more generally about our exposure to major disruptions.

The trade bans are harming both Australia and China, with those businesses and employees producing (and consuming) the targeted products bearing the brunt of the cost.

Assessing the scale of the impact is difficult, as it depends on time frames and our resilience to shocks.

An important factor is China’s importance to us as an export destination. It is our single largest market, accounting for over a third of exports, and that share has increased rapidly – especially for mineral resources.

To illustrate, nine years ago, just 4 per cent of our LNG exports were destined to China. By last year that figure was 34 per cent.

According to some, these stylised facts make Australia highly vulnerable. For example, a recent report by ASPI (2021) noted the lack of diversity in Australia’s trade ties and that the high dependence on a few commodities would accentuate the economic costs of an extreme event of a cessation of bilateral trade with China.

The Productivity Commission conducted its own assessment on the vulnerability of Australia’s export (and import) supply chains and our analysis reached less alarmist conclusions.

Looking at the concentration of exports by market and product is a good starting point, but not sufficient to make unequivocal conclusions.

Contrary to perceptions, we found that Australia lies very much in the middle of the road in terms of the importance of our major export destinations and our major export products.

Australia’s share of exports going to the top 10 destination markets is 79 per cent, compared to a global average of 72 per cent - and 86 per cent in Canada, another resource-rich economy. And using this concentration metric for the top ten exported products, Australia sits slightly below the global average, at 68 per cent (see figure).

Higher degrees of concentration are to be expected in a more globalised and specialised world.

Countries specialise in exporting the products and services that best match their resources and capabilities. And destination markets closer to Australia are more attractive to exporters because they can save on transport costs and limit other frictions associated with distance.

The key question to ask in assessing the degree of vulnerability and resilience is whether there are alternative markets if, for whatever reason, access to the main trading partner disappears.

To answer this question, the Productivity Commission first calculated the share of each export (there are some 4900 different product groups) which are concentrated in one market (defined as accounting for 80 per cent or more of the value of that export).

Applying this filter identifies about 1 in 5 exports being sold in concentrated markets – predominantly to China.

But this does not necessarily imply large economic damages from China’s trade sanctions, because for many of these highly geographically concentrated exports, the global trade in those products is not concentrated.

It turns out that Australia could, if needed, export to other destination markets, reducing the economic cost of any disruption.

On our reckoning, less than 1-in-100 Australian exports is vulnerable to concentrated sources of global demand. Disruptions to these products are likely to be more costly.

Examples of the 35 Australian products identified as vulnerable due to concentrated sources of global demand include bauxite, fresh rock lobsters, and certain timber products.

The trade bans imposed by China in 2020 provide an opportunity to test this reasoning and whether disruptions to highly concentrated products are relatively more costly.

We found some evidence that they were.

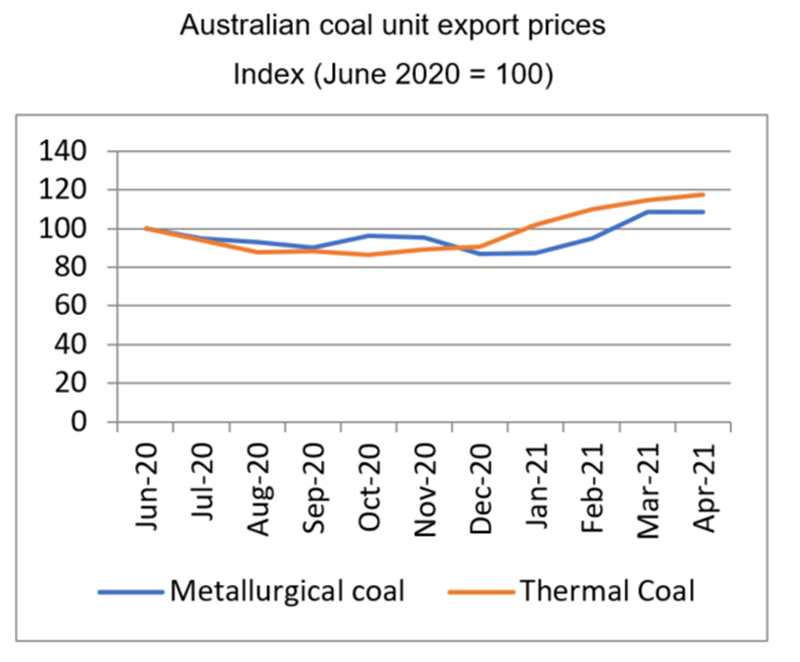

With coal exports - not classified as vulnerable, because there are alternative markets for Australian coal - the trade ban led to some initial losses and lower prices as exporters scrambled to find new markets. But after six months, the value of coal exports and prices for coal had more than recovered (see figure).

Australian coal unit export prices

Index (June 2020 = 100)

Image

Sources: DISER (2021); DFAT (2021).

Conversely, products such as timber and rock lobsters, which were classified as vulnerable, have struggled to find alternative markets, including the domestic market. The price of rock lobsters has plummeted.

This more benign assessment of the risks associated with disruptions to exports may be small comfort to those regions in Australia most affected by trade bans.

South Australia, for example, exports timber, rock lobsters and wine, all of which have been affected by Chinese policies.

Wine is a product where reputation and customer experience play a large role in building new sales.

This makes it slower and more costly to build up alternative markets than it is for a commodity such as coal. But judicious market prospection before a disruption occurs can reduce the time required to develop new markets.

Not all disruptions to exports are associated with highly concentrated markets. For example, education and tourism – Australia’s biggest services exports – have been severely impacted by the bans on arrivals from all countries that were introduced to limit infection from Covid-19.

Iron ore is another interesting example. It is identified as ‘vulnerable’, accounting for a fifth of our total exports and virtually all of it going to China, which imports two-thirds of the world’s iron ore.

All iron ore exporters are vulnerable to changes in market conditions. The recent mandated slowdown in Chinese steel production, for example, has led to a large fall in iron ore prices.

But how should Australia respond to that vulnerability?

Iron ore exporters could seek new markets, but prices would be much lower in those markets. Taking advantage of high prices while they last, while preparing for the future decline, seems like the most profitable strategy.

A complete ban on iron ore from Australia seems unlikely, because just as Australia’s iron ore is vulnerable to China, China’s steel is vulnerable to Australian iron ore. Until the Brazilian mining industry fully recovers, and new mines in Africa become operational, a ban would mean a drastic fall in Chinese steel production, with flow-on effects to the Chinese economy.

In sum, while geopolitical and COVID risks have certainly increased, Australia’s exposure to export disruptions in highly concentrated markets is not unique, and for many products there are alternative markets.

We should also take some comfort from the stress test of recent export bans. They tell us that Australia’s export situation is not as dire as some of the more alarmist scenarios make out.

This article was written by Commissioner Catherine de Fontenay and Special Adviser Jonathan Coppel. It was also published in the Australian Financial Review (page 39) on Tuesday 31 August 2021.

Related publications