Report on Government Services 2022

PART E, SECTION 12: RELEASED ON 1 FEBRUARY 2022

12 Public hospitals

Impact of COVID-19 on data for the Public hospitals section

COVID-19 may affect data in this Report in a number of ways. This includes in respect of actual performance (that is, the impact of COVID-19 on service delivery during 2020 and 2021 which is reflected in the data results), and the collection and processing of data (that is, the ability of data providers to undertake data collection and process results for inclusion in the Report).

For the Public hospitals section, COVID-19 has had an impact on emergency department presentations with fewer presentations to emergency departments and declines in presentations due to injuries. Similarly, elective surgery data were impacted by COVID-19 due to the temporary suspension of some elective surgeries, resulting in a decrease in the number of surgeries performed.

This section reports on the performance of governments in providing public hospitals, with a focus on acute care services.

The Indicator Results tab uses data from the data tables to provide information on the performance for each indicator in the Indicator Framework. The same data are also available in CSV format.

- Context

- Indicator framework

- Indicator results

- Indigenous data

- Key terms and references

Objectives for public hospitals

Public hospitals aim to alleviate or manage illness and the effects of injury by providing acute, non and sub-acute care along with emergency and outpatient care that is:

- timely and accessible to all

- appropriate and responsive to the needs of individuals throughout their lifespan and communities

- high quality and safe

- well coordinated to ensure continuity of care where more than one service type, and/or ongoing service provision is required

- sustainable.

Governments aim for public hospital services to meet these objectives in an equitable and efficient manner.

Service overview

Public hospitals provide a range of services, including:

- acute care services to admitted patients

- subacute and non-acute services to admitted patients (for example, rehabilitation, palliative care and long stay maintenance care)

- emergency, outpatient and other services to non-admitted patients

- mental health services, including services provided to admitted patients by designated psychiatric/psychogeriatric units

- public health services

- teaching and research activities.

This section focuses on services (acute, subacute and non-acute) provided to admitted patients and services provided to non-admitted patients in public hospitals. These services comprise the bulk of public hospital activity.

In some instances, data for stand-alone psychiatric hospitals are included in this section. The performance of psychiatric hospitals and psychiatric units of public hospitals is examined more closely in the ‘Services for mental health’ section of this Report (section 13).

Funding

Total recurrent expenditure on public hospitals (excluding depreciation) was $76.7 billion in 2019‑20 (table 12A.1), with 93 per cent funded by the Australian, State and Territory governments and 7 per cent funded by non-government sources (including depreciation) (AIHW 2021).

Government real recurrent expenditure (all sources) on public hospitals per person was $2971 in 2019‑20; an increase of 1.6 per cent from 2018-19 ($2924, table 12A.2).

Size and scope

Hospitals

In 2019‑20, Australia had 695 public hospitals – 3 more than 2018‑19 (table 12A.3). Although 68.6 per cent of hospitals had 50 or fewer beds (figure 12.1), these smaller hospitals represented only 13.2 per cent of total available beds (table 12A.3).

Hospital beds

There were 62 575 available beds for admitted patients in public hospitals in 2019‑20 (table 12.1), equivalent to 2.5 beds per 1000 people (tables 12A.3–4). The concept of an available bed is becoming less important in the overall context of hospital activity, particularly given the increasing significance of same day hospitalisations and hospital-in-the-home (AIHW 2021a; Montalto et al 2020). Nationally, the number of beds available per 1000 people increased as remoteness increased (table 12A.4).

Admitted patient care

There were approximately 6.7 million separations from public (non-psychiatric) hospitals in 2019‑20, of which just over half (54.7 per cent) were same day patients (table 12A.5). Nationally, this equates to 244.1 separations per 1000 people (figure 12.2). Acute care separations accounted for 93.9 per cent of separations from public hospitals (table 12A.10).

Variations in admission rates can reflect different practices in classifying patients as either admitted same day patients or non-admitted outpatients. The extent of differences in classification practices can be inferred from the variation in the proportion of same day separations across jurisdictions for certain conditions or treatments. This is particularly true of medical separations, where there was significant variation across jurisdictions in the proportion of same day medical separations in 2019-20 (table 12A.7).

In 2019-20, on an age-standardised basis, public hospital separation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were markedly higher than the corresponding rates for all people. For private hospital separations, rates were higher for all people compared to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (though separations are lower for private hospitals compared to public hospitals) (table 12A.8).

Non-admitted patient services

Non-admitted patient services include outpatient services, which may be provided on an individual or group basis, and emergency department services. A total of 37.2 million individual service events were provided to outpatients in public hospitals in 2019-20 and 958 337 group service events (table 12A.11). Differing admission practices across states and territories lead to variation among jurisdictions in the services reported (AIHW 2021b). There were 8.8 million presentations to emergency departments in 2020‑21 (table 12A.12).

Staff

In 2019‑20, nurses comprised the single largest group of full time equivalent (FTE) staff employed in public hospitals (figure 12.3). Comparing data on FTE staff across jurisdictions should be undertaken with care, as these data are affected by jurisdictional differences in the recording and classification of staff.

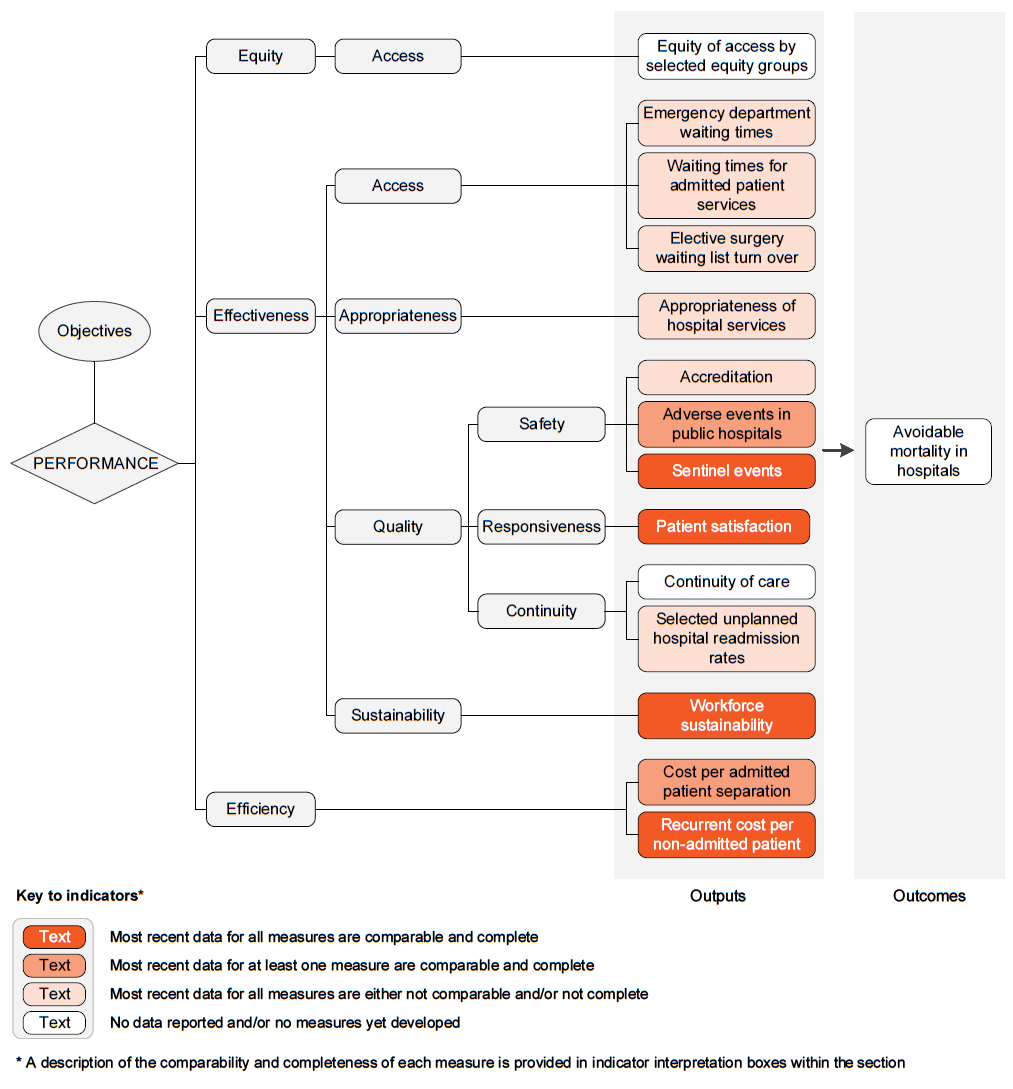

The performance indicator framework provides information on equity, efficiency and effectiveness, and distinguishes the outputs and outcomes of public hospital services.

The performance indicator framework shows which data are complete and comparable in this Report. For data that are not considered directly comparable, text includes relevant caveats and supporting commentary. Section 1 discusses data comparability and completeness from a Report-wide perspective. In addition to the contextual information for this service area (see Context tab), the Report’s statistical context (section 2) contains data that may assist in interpreting the performance indicators presented in this section.

Improvements to performance reporting for public hospital services are ongoing and include identifying data sources to fill gaps in reporting for performance indicators and measures, and improving the comparability and completeness of data.

Outputs

Outputs are the services delivered (while outcomes are the impact of these services on the status of an individual or group) (see section 1). Output information is also critical for equitable, efficient and effective management of government services.

Outcomes

Outcomes are the impact of services on the status of an individual or group (see section 1).

An overview of the Public hospital services performance indicator results are presented. Different delivery contexts, locations and types of clients can affect the equity, effectiveness and efficiency of public hospital services.

Information to assist the interpretation of these data can be found with the indicators below and all data (footnotes and data sources) are available for download from Download supporting material. Data tables are identified by a ‘12A’ prefix (for example, table 12A.1).

All data are available for download as an excel spreadsheet and as a CSV dataset — refer to Download supporting material. Specific data used in figures can be downloaded by clicking in the figure area, navigating to the bottom of the visualisation to the grey toolbar, clicking on the 'Download' icon and selecting 'Data' from the menu. Selecting 'PDF' or 'Powerpoint' from the 'Download' menu will download a static view of the performance indicator results.

1. Equity of access by selected equity groups

‘Equity of access by selected equity groups’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide hospital services in an equitable manner.

‘Equity of access by selected equity groups’ is measured for the selected equity group of people living in remote and very remote areas and is defined as the percentage of people who delayed going to hospital due to distance from hospital, by region.

Similar rates across regions can indicate equity of access to hospital services across regions.

Data are not yet available for reporting against this measure. However, data sourced from the ABS Patient Experience Survey are expected to be available to enumerate this indicator for the 2023 Report.

2. Emergency department waiting times

‘Emergency department waiting times’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide timely and accessible services to all.

‘Emergency department waiting times’ is defined by the following two measures:

- Emergency department waiting times by triage category, defined as the proportion of patients seen within the benchmarks set by the Australasian Triage Scale. The Australasian Triage Scale is a scale for rating clinical urgency, designed for use in hospital-based emergency services in Australia and New Zealand. The benchmarks, set according to triage category, are as follows:

- triage category 1: need for resuscitation — patients seen immediately

- triage category 2: emergency — patients seen within 10 minutes

- triage category 3: urgent — patients seen within 30 minutes

- triage category 4: semi-urgent — patients seen within 60 minutes

- triage category 5: non-urgent — patients seen within 120 minutes.

- Proportion of patients staying for four hours or less, is defined as the proportion of presentations to public hospital emergency departments where the time from presentation to admission, transfer or discharge is less than or equal to four hours. It is a measure of the duration of the emergency department service rather than a waiting time for emergency department care.

High or increasing proportions for both measures are desirable.

The comparability of emergency department waiting times data across jurisdictions can be influenced by differences in data coverage and clinical practices — in particular, the allocation of cases to urgency categories. The proportion of patients in each triage category who were subsequently admitted can indicate the comparability of triage categorisations across jurisdictions and thus the comparability of the waiting times data (table 12A.13).

Nationally in 2020-21, all patients in triage category 1 were seen within the clinically appropriate timeframe. For all triage categories combined, an estimated 71 per cent of patients were seen within triage category timeframes (table 12.2).

The proportion of patients staying for four hours or less in an emergency department was 67.0 per cent in 2020-21; continuing an annual decrease from 73.2 per cent in 2015-16 (figure 12.4).

3. Waiting times for admitted patient services

‘Waiting times for admitted patient services’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide timely and accessible services to all.

‘Waiting times for admitted patient services’ is defined by the following three measures:

- Overall elective surgery waiting times

- Elective surgery waiting times by clinical urgency category

- Presentations to emergency departments with a length of stay of 4 hours or less ending in admission.

Overall elective surgery waiting times

‘Overall elective surgery waiting times’ are calculated by comparing the date patients are added to a waiting list with the date they were admitted. Days on which the patient was not ready for care are excluded. Overall waiting times are presented as the number of days within which 50 per cent of patients are admitted and the number of days within which 90 per cent of patients are admitted. Patients on waiting lists who were not subsequently admitted are excluded.

For overall elective surgery waiting times, a low or decreasing number of days waited is desirable. Comparisons across jurisdictions should be made with caution, due to differences in clinical practices and classification of patients across Australia. The measures are also affected by variations across jurisdictions in the method used to calculate waiting times for patients who transferred from a waiting list managed by one hospital to a waiting list managed by another hospital, with the time waited on the first list included in the waiting time reported in NSW, WA, SA and the NT. This approach can have the effect of increasing the apparent waiting times for admissions in these jurisdictions compared with other jurisdictions.

Nationally in 2020-21, 50 per cent of patients were admitted within 48 days (up from 39 days in 2019-20) and 90 per cent of patients were admitted within 348 days (up from 281 days in 2019-20) (figure 12.5). Data are available on elective surgery waiting times by hospital peer group and indicator procedure, Indigenous status, remoteness and socioeconomic status (tables 12A.19–22).

Elective surgery waiting times by clinical urgency category

‘Elective surgery waiting times by clinical urgency category’ reports the proportion of patients who were admitted from waiting lists after an extended wait. In general, at the time of being placed on the public hospital waiting list, a clinical assessment is made of the urgency with which the patient requires elective surgery. The clinical urgency categories are:

- Category 1 — procedures that are clinically indicated within 30 days

- Category 2 — procedures that are clinically indicated within 90 days

- Category 3 — procedures that are clinically indicated within 365 days.

The term ‘extended wait’ is used for patients in categories 1, 2 and 3 waiting longer than specified times (30 days, 90 days and 365 days respectively).

For elective surgery waiting times by clinical urgency category, a low or decreasing proportion of patients who have experienced extended waits at admission is desirable. However, variation in the way patients are classified to urgency categories should be considered. Rather than comparing jurisdictions, the results for individual jurisdictions should be viewed in the context of the proportions of patients assigned to each of the three urgency categories.

Jurisdictional differences in the classification of patients by urgency category are shown in table 12.3a. The proportions of patients on waiting lists who already had an extended wait at the date of assessment are reported in tables 12A.24–31.

Presentations to emergency departments with a length of stay of 4 hours or less ending in admission

‘Presentations to emergency departments with a length of stay of 4 hours or less ending in admission’ is defined as the proportion of presentations to public hospital emergency departments where the time from presentation to admission to hospital is less than or equal to 4 hours.

A high or increasing proportion of presentations to emergency departments with a length of stay of 4 hours or less ending in admission is desirable.

Nationally in 2020-21, 42 per cent of people who presented to an emergency department and were admitted, waited 4 hours or less to be admitted to a public hospital (table 12.3b). This proportion has declined each year over the 5 years of reported data.

4. Elective surgery waiting list turn over

‘Elective surgery waiting list turn over’ is an indicator of government’s objective to provide timely and accessible services to all.

‘Elective surgery waiting list turn over’ is defined as the number of additions to, and removals from, public hospital elective surgery waiting lists. It is measured as the number of people removed from public hospital elective surgery waiting lists following admission for surgery during the reference year, divided by the number of people added to public hospital elective surgery waiting lists during the same year, multiplied by 100.

The number of people removed from public hospital elective surgery waiting lists following admission for surgery includes elective and emergency admissions. For context, the total number of removals from elective surgery waiting lists are also reported. Other reasons for removal include; patient not contactable or died, patient treated elsewhere, surgery not required or declined, transferred to another hospital's waiting list, and not reported.

When interpreting these data, 100 per cent indicates that an equal number of patients were added to public hospital elective surgery waiting lists as were removed following admission for surgery during the reporting period (therefore the number of patients on the waiting list will be largely unchanged). A figure less than 100 per cent indicates that more patients were added to public hospital elective surgery waiting lists than were removed following admission for surgery during the reporting period (therefore the number of patients on the waiting list will have increased).

A higher and increasing per cent of patient turn over is desirable as it indicates the public hospital system is keeping pace with demand for elective surgery.

Nationally in 2020-21, 893 163 people were added to public hospital elective surgery waiting lists, while 754 600 people were removed following admission for surgery, resulting in a national public hospital elective surgery waiting list turn over of 84.5 per cent (table 12.4). Results varied across jurisdictions.

5. Appropriateness of hospital services

'Appropriateness of hospital services’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide care that is appropriate and responsive to the needs of individuals throughout their lifespan and communities.

'Appropriateness of hospital services’ is defined as the proportion of patients who discharge against medical advice and is measured as:

- Emergency department presentations:

- patients who did not wait, as a proportion of all emergency department presentations

- patients who left at their own risk, as a proportion of all emergency department presentations

- Admitted patient care separations:

- patients who left or were discharged against medical advice, as a proportion of all hospital separations.

'Did not wait' refers to patients who did not wait for clinical care to commence or medical assessment following triage in the emergency department. 'Left at own risk' refers to patients who left against advice after treatment had commenced. This includes patients who were planned for admission but who did not physically leave the emergency department prior to departing. 'Discharge against medical advice' refers to patients who were admitted to hospital and left against the advice of their treating physician.

Patients who do not wait, leave at own risk and discharge against medical advice are at an increased risk of complications, readmission and mortality. Low or decreasing proportions of patients who do not wait, leave at own risk and discharge against medical advice are desirable. Broader, system-level definitions of appropriate health care include dimensions such as evidence-based care, variations in clinical practice and resource use. Additional measures for this indicator will be considered for inclusion in future editions of this Report.

Nationally in 2019-20, 3.6 per cent of emergency department presentations did not wait, while 2.2 per cent of emergency department presentations left at their own risk. Additionally, 1.2 per cent of admitted patients left or were discharged against medical advice (table 12.5). Proportions for all measures were higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than for non-Indigenous people.

6. Accreditation

‘Accreditation’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide public hospital services that are high quality and safe.

‘Accreditation’ is defined as public hospitals accredited to the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (the Standards) and is measured as:

- the number of public hospitals accredited, as a proportion of all public hospitals assessed for accreditation in the same calendar year

- the number of public hospitals accredited during the calendar year that required actions to achieve accreditation, as a proportion of all public hospitals accredited during the same calendar year.

It is mandatory for all hospitals and day procedure services to be accredited to the Standards. Health service organisations must demonstrate that they meet all of the requirements in the Standards to achieve accreditation. Reaccreditation against the Standards is required every three years. The standards are:

- Clinical governance

- Partnering with consumers

- Preventing and controlling healthcare-associated infection

- Medication safety

- Comprehensive care

- Communicating for safety

- Blood management

- Recognising and responding to acute deterioration.

A high or increasing rate of accreditation is desirable. Accreditation against the Standards is evidence that a hospital has been able to demonstrate compliance with the Standards. It does not mean that an accredited hospital will always provide high quality and safe care. In addition, there are differences across jurisdictions in: (1) the proportion of public hospitals opting for announced or short-notice assessments (from 2023, short-notice assessments will be mandatory); and (2) the mix of hospitals that were assessed (for example, large metropolitan hospitals and small rural services). This indicator should be interpreted in conjunction with other indicators of public hospital quality and safety.

Nationally in 2020, 30 per cent of public hospitals that were accredited during the year required remedial actions to achieve accreditation (table 12.6). This is consistent with the proportion in 2019. However, due to the temporary suspension of the national accreditation program in March 2020 as a result of COVID-19, fewer hospitals were accredited in 2020 (33) compared to 2019 (181) (table 12A.35). During this period of temporary program suspension, hospitals and day procedure services maintained their existing accreditation status (ACSQHC 2020).

7. Adverse events in public hospitals

‘Adverse events in public hospitals’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide public hospital services that are high quality and safe. Sentinel events, which are a subset of adverse events that result in death or very serious harm to the patient, are reported as a separate output indicator.

‘Adverse events in public hospitals’ is defined by the following three measures:

- Selected healthcare-associated infections

- Adverse events treated in hospitals

- Falls resulting in patient harm in hospitals.

Selected healthcare-associated infections

‘Selected healthcare-associated infections’ is the number of Staphylococcus aureus (including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]) bacteraemia (SAB) patient episodes associated with public hospitals (admitted and non-admitted patients), expressed as a rate per 10 000 patient days for public hospitals.

A patient episode of SAB is defined as a positive blood culture for SAB. Only the first isolate per patient is counted, unless at least 14 days has passed without a positive blood culture, after which an additional episode is recorded.

SAB is considered to be healthcare-associated if the first positive blood culture is collected more than 48 hours after hospital admission or less than 48 hours after discharge, or if the first positive blood culture is collected less than or equal to 48 hours after admission to hospital and the patient episode of SAB meets at least one of the following criteria:

- SAB is a complication of the presence of an indwelling medical device

- SAB occurs within 30 days of a surgical procedure where the SAB is related to the surgical site

- SAB was diagnosed within 48 hours of a related invasive instrumentation or incision

- SAB is associated with neutropenia contributed to by cytotoxic therapy. Neutropenia is defined as at least two separate calendar days with values of absolute neutrophil count (ANC) or total white blood cell count <500 cell/mm3 (0.5 × 109/L) on or within a seven-day time period which includes the date the positive blood specimen was collected (Day 1), the three calendar days before and the three calendar days after.

Cases where a known previous positive test has been obtained within the last 14 days are excluded. Patient days for unqualified newborns, hospital boarders and posthumous organ procurement are excluded.

A low or decreasing rate of selected healthcare-associated infections is desirable.

Nationally in 2020-21, the rate of selected healthcare-associated infections was 0.7 per 10 000 patient days (figure 12.6a).

Adverse events treated in hospitals

‘Adverse events treated in hospitals’ are incidents in which harm resulted to a person during hospitalisation and are measured by separations that had an adverse event (including infections, falls resulting in injuries and problems with medication and medical devices) that occurred during hospitalisation. Hospital separations data include information on diagnoses and place of occurrence that can indicate that an adverse event was treated and/or occurred during the hospitalisation, but some adverse events are not identifiable using these codes.

Low or decreasing adverse events treated in hospitals are desirable.

Nationally in 2019-20, 6.3 per cent of separations in public hospitals had an adverse event reported during hospitalisation (table 12.7). Results by category (diagnosis, external cause and place of occurrence of the injury or poisoning) are in table 12A.37.

Falls resulting in patient harm in hospitals

‘Falls resulting in patient harm in hospitals’ is defined as the number of separations with an external cause code for fall and a place of occurrence of health service area, expressed as a rate per 1000 hospital separations. It is not possible to determine if the place of occurrence was a public hospital, only that it was a health service area.

A low or decreasing rate of falls resulting in patient harm in hospitals is desirable.

Nationally in 2019-20, the rate of falls resulting in patient harm was 5.0 per 1000 hospital separations; results varied across states and territories (figure 12.6b). Data are reported by Indigenous status and remoteness in table 12A.38.

8. Sentinel events

‘Sentinel events’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to deliver public hospital services that are high quality and safe. Sentinel events are a subset of adverse events that result in death or very serious harm to the patient. Adverse events are reported as a separate output indicator.

‘Sentinel events’ is defined as the number of reported adverse events that occur because of hospital system and process deficiencies, and which result in the death of, or serious harm to, a patient. Sentinel events occur relatively infrequently and are independent of a patient’s condition.

Australian health ministers agreed version 2 of the Australian sentinel events list in December 2018. All jurisdictions implemented these categories on 1 July 2019. The national sentinel events are:

- Surgery or other invasive procedure performed on the wrong site resulting in serious harm or death

- Surgery or other invasive procedure performed on the wrong patient resulting in serious harm or death

- Wrong surgical or other invasive procedure performed on a patient resulting in serious harm or death

- Unintended retention of a foreign object in a patient after surgery or other invasive procedure resulting in serious harm or death

- Haemolytic blood transfusion reaction resulting from ABO blood type incompatibility resulting in serious harm or death

- Suspected suicide of a patient in an acute psychiatric unit or acute psychiatric ward

- Medication error resulting in serious harm or death

- Use of physical or mechanical restraint resulting in serious harm or death

- Discharge or release of an infant or child to an unauthorised person

- Use of an incorrectly positioned oro-or naso-gastric tube resulting in serious harm or death.

A low or decreasing number of sentinel events is desirable.

Sentinel event programs have been implemented by all State and Territory governments. The purpose of these programs is to facilitate a safe environment for patients by reducing the frequency of these events. The programs are not punitive, and are designed to facilitate self‑reporting of errors so that the underlying causes of the events can be examined, and action taken to reduce the risk of these events re-occurring.

Changes in the number of sentinel events reported over time do not necessarily mean that Australian public hospitals have become more or less safe, but might reflect improvements in incident reporting mechanisms, organisational cultural change, and/or an increasing number of hospital admissions (these data are reported as numbers rather than rates). Trends need to be monitored to establish the underlying reasons.

In 2019-20, there was a total of 57 sentinel events (table 12.8). As larger states and territories will tend to have more sentinel events than smaller jurisdictions, the numbers of separations are also presented to provide context. Data disaggregated by the type of sentinel event are reported in table 12A.39. Sentinel event data for prior years, reported against the previous version of the Australian sentinel events list, are available in earlier editions of this Report.

9. Patient satisfaction

‘Patient satisfaction’ provides a proxy measure of governments’ objective to deliver services that are responsive to individuals throughout their lifespan and communities.

‘Patient satisfaction’ is defined by the following six measures for the purposes of this Report:

- Proportion of people who went to an emergency department in the last 12 months for their own health reporting that the emergency department doctors, specialists or nurses ‘always’ or ‘often’:

- listened carefully to them

- showed respect to them

- spent enough time with them

- Proportion of people who were admitted to hospital in the last 12 months reporting that the hospital doctors, specialists or nurses ‘always’ or ‘often’:

- listened carefully to them

- showed respect to them

- spent enough time with them.

A high or increasing proportion of patients who were satisfied is desirable, as it suggests the hospital care was of high quality and better met the expectations and needs of patients.

The ABS Patient Experience Survey of people aged 15 years and over does not include people living in discrete Indigenous communities, which affects the representativeness of the NT results. Approximately 20 per cent of the resident population of the NT live in discrete Indigenous communities.

In 2020-21, nationally for all measures, the rate of respondents reporting that hospital and emergency department doctors, specialists and nurses listened carefully, showed respect and spent enough time with them was above 82 per cent. Generally respondents reported more positive experiences with nurses compared to doctors and specialists, and in hospitals compared to emergency departments (figures 12.7a and 12.7b).

10. Continuity of care

‘Continuity of care’ is an indicator of government’s objective to provide care that is well co‑ordinated to ensure continuity of care where more than one service type, and/or ongoing service provision is required.

‘Continuity of care’ is defined by four measures:

- the number of hospital patients with complex needs for which a discharge plan is provided within 5 days of discharge divided by all hospital patients with complex care needs expressed as a rate per 1000 separations

- the proportion of patients reporting that their usual GP, or others in their usual place of care, did not seem informed of their follow up needs or medication changes after the last time they went to a hospital emergency department

- the proportion of patients reporting that their usual GP, or others in their usual place of care, did not seem informed of their follow up needs or medication changes after the last time they were admitted to hospital

- the proportion of patients who reported that arrangements were not made by their hospital for any services needed after leaving hospital when last admitted.

High or increasing rates of discharge plans provided to patients with complex care needs within 5 days is desirable. While it is desirable for discharge plans to be provided to patients, the indicator does not provide any information on whether the discharge plan was carried out or whether it was effective in improving patient outcomes.

Low or decreasing proportions of patients reporting that their GP, or others in their usual place of care, did not seem informed of their follow up needs or medication changes after the last time they went to a hospital emergency department or were admitted to hospital are desirable. A low or decreasing proportion of patients reporting that arrangements were not made by their hospital for any services needed after leaving hospital when last admitted is desirable.

Data are not yet available for reporting against these measures. However, summary data from the 2016 ABS survey of health care are available to report as contextual information for measures 2–4 for people aged 45 years and over in table 12A.44.

11. Selected unplanned hospital readmission rates

‘Selected unplanned hospital readmission rates’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide public hospital services that are of high quality and well-coordinated to ensure continuity of care.

‘Selected unplanned hospital readmission rates’ is defined as the rate at which patients unexpectedly return to the same hospital within 28 days for further treatment where the original admission involved one of a selected set of procedures, and the readmission is identified as a post-operative complication. It is expressed as a rate per 1000 separations in which one of the selected surgical procedures was performed. The indicator is an underestimate of all possible unplanned/unexpected readmissions.

The selected surgical procedures are knee replacement, hip replacement, tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, hysterectomy, prostatectomy, cataract surgery and appendectomy. Unplanned readmissions are those having a principal diagnosis of a post-operative adverse event for which a specified ICD-10-AM diagnosis code has been assigned.

Low or decreasing rates of unplanned readmissions are desirable. Conversely, high or increasing rates suggest the quality of care provided by hospitals, or post-discharge care or planning, should be examined, because there may be scope for improvement.

Of the selected surgical procedures in 2019-20, readmission rates were highest nationally, and for most jurisdictions, for tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy, with the rate for adenoidectomy increasing from 21.7 to 41.5 readmissions per 1000 separations over the past 10 years (table 12.9). Selected unplanned hospital readmission rates are reported by hospital peer group, Indigenous status, remoteness and socioeconomic status in table 12A.46.

12. Workforce sustainability

‘Workforce sustainability’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to provide sustainable public hospital services.

‘Workforce sustainability’ reports age profiles for the nursing and midwifery workforce and the medical practitioner workforce. It shows the proportions of registered nurses and midwives, and medical practitioners in ten year age brackets, by jurisdiction and by region.

High or increasing proportions of the workforce that are new entrants and/or low or decreasing proportions of the workforce that are close to retirement are desirable.

All nurses, midwives and medical practitioners in the workforce are included in these measures, as crude indicators of the potential respective workforces for public hospitals.

These measures are not a substitute for a full workforce analysis that allows for migration, trends in full-time work and expected demand increases. They can, however, indicate that further attention should be given to workforce sustainability for public hospitals.

Nationally in 2020, 12.2 per cent of the FTE nursing workforce were aged 60 years and over (figure 12.8a). This proportion has increased from 10.3 per cent in 2013, but may be partially offset by a corresponding increase in the proportion of the nursing workforce aged under 40 years (table 12A.47).

For the medical practitioner workforce, the proportion aged 60 years and over was 15.2 per cent in 2020 (figure 12.8b). While this proportion is higher than 2013, it represents the first decrease over the eight years of reported data (table 12A.49). Similar to the nursing workforce, the proportion of the medical practitioner workforce aged under 40 years has increased over this period.

For both the nursing and medical practitioner workforce, the proportion aged 60 years and over is higher in remote areas compared to non-remote areas (tables 12A.47 and 12A.49).

13. Cost per admitted patient separation

‘Cost per admitted patient separation’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to deliver services in an efficient manner.

‘Cost per admitted patient separation’ is defined by the following two measures:

- Recurrent cost per weighted separation

- Capital cost per weighted separation.

A low or decreasing recurrent cost per weighted separation or capital cost per weighted separation can reflect more efficient service delivery in public hospitals. However, this indicator needs to be viewed in the context of the set of performance indicators as a whole, as decreasing cost could also be associated with decreasing quality and effectiveness.

Recurrent cost per weighted separation

‘Recurrent cost per weighted separation’ is the average cost of providing care for an admitted patient (overnight stay or same day) adjusted for casemix. Casemix adjustment takes account of variation in the relative complexity of the patient’s clinical condition and of the hospital services provided, but not other influences on length of stay.

Nationally in 2019-20, the recurrent cost per weighted separation was $5161, up from $4989 in 2018-19 and the first increase for the five years of reported data (figure 12.9a). Data on the average cost per admitted patient separation are available on the subset of presentations that are acute emergency department presentations (table 12A.53).

Capital cost per weighted separation

‘Capital cost per weighted separation’ is calculated as the user cost of capital (calculated as 8 per cent of the value of non-current physical assets including buildings and equipment but excluding land) plus depreciation, divided by the number of weighted separations.

This measure allows the full cost of hospital services to be considered. Depreciation is defined as the cost of consuming an asset’s services. It is measured by the reduction in value of an asset over the financial year. The user cost of capital is the opportunity cost of the capital invested in an asset, and is equivalent to the return foregone from not using the funds to deliver other services or to retire debt. Interest payments represent a user cost of capital, so are deducted from capital costs to avoid double counting.

Costs associated with non-current physical assets are important components of the total costs of many services delivered by government agencies. Nationally in 2019-20, the total capital cost (excluding land) per weighted separation was $1257 (figure 12.9b).

14. Recurrent cost per non-admitted patient

‘Recurrent cost per non-admitted patient’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to deliver services in an efficient manner.

‘Recurrent cost per non-admitted patient’ is defined by the following two measures:

- Average cost per non-admitted acute emergency department presentation

- Average cost per non-admitted service event.

A low or decreasing recurrent cost per non-admitted patient can reflect more efficient service delivery in public hospitals. However, this indicator should be viewed in the context of the set of performance indicators as a whole, as decreasing cost could also be associated with decreasing quality and effectiveness. This indicator does not adjust for the complexity of service.

Nationally in 2019-20, the average cost per non-admitted emergency department presentation was $595 (figure 12.10a) and per non-admitted service event was $337 (figure 12.10b). For both measures the costs per non-admitted patient have increased over the five years of reported data

15. Avoidable mortality in hospitals

‘Avoidable mortality in hospitals’ is an indicator of governments’ objective to alleviate or manage illness and the effects of injury.

‘Avoidable mortality in hospitals’ is defined as death in low-mortality diagnostic related groups (DRGs) expressed as a rate.

Low or decreasing rates of avoidable mortality in hospitals indicate more successful management of illness and the effects of injury.

Data are not yet available for reporting against this measure. Table 12.10 provides an overview of the review mechanisms in place across states and territories for examining in-hospital deaths.

NSW | NSW reports publicly on selected mortality in hospitals data. The report 'Mortality following hospitalisation for seven clinical conditions' provides information on patient deaths within 30 days of admission across 73 public hospitals for seven clinical conditions during the period July 2015 to June 2018 http://www.bhi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/557827/BHI_Mortality_2015-2018_REPORT.pdf). The seven clinical conditions are: acute myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, congestive heart failure, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip fracture surgery. Together these conditions account for approximately 11 per cent of acute emergency hospitalisations for people aged 15 years and over in NSW, and approximately 28 per cent of in-hospital deaths following acute emergency hospitalisation. The NSW Bureau of Health Information uses 30-day risk-standardised mortality ratios (RSMRs) to assess mortality in hospital. The RSMRs take into account the volume of patients treated and key patient risk factors beyond the control of a hospital. However, not all relevant risk factors are recorded, such as sociological and environmental factors, so while results are useful for trend analysis and a guide for further investigation, they are not suitable for direct performance comparisons. A ratio of less than 1.0 indicates that mortality is lower than expected in a given hospital, while a ratio of greater than 1.0 indicates that mortality is higher than expected in a given hospital. Three years of data are used to create stable, reliable estimates of performance. Rates are also reported per 100 hospitalisations for each of the seven clinical conditions. |

|---|---|

Victoria | Victoria does not report publicly on these data. However, Victoria reports internally on five indicators based on the Core Hospital-Based Outcome Indicator (CHBOI) specifications published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC); Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio and In-hospital Mortality (for Stroke, Fractured Neck-of-Femur, Acute Myocardial Infarction and Pneumonia). Outliers for these indicators are reviewed on a regular basis by Safer Care Victoria, the Department of Health and Human Services and respective health services as part of the performance monitoring process. In addition, the Victorian Perioperative Consultative Council oversees, reviews and analyses cases of perioperative mortality and morbidity in Victoria. Victoria also reports internally on four in-hospital mortality indicators (for Stroke, Fractured Neck of Femur, Acute Myocardial Infarction and Pneumonia) via the Victorian Agency for Health Information Private Hospitals Quality and Safety Report. The Victorian Agency for Health Information (VAHI) previously reported on deaths in low mortality DRGs based on the CHBOI specifications. Following further methodological review during 2018-19, an updated indicator has been defined and re-introduced for internal reporting as part of the Boards Quality and Safety Report. The calculation is restricted to acute-care separations where the DRG is classified as a low-mortality DRG, which is defined as a DRG with a national mortality rate of less than 0.5 per cent over the previous 3 years, as at the time of calculation. |

Queensland | Queensland does not report publicly on these data. Queensland Hospital and Health Services undertake 'outlier' reviews of in-hospital deaths which are reviewed by a statewide committee to ensure the review is thorough and actions are identified for any issues found. The need for review is identified through monitoring condition or procedure specific indicators (AMI, Heart Failure, Stroke, Fractured Neck of Femur and Pneumonia) and system-wide mortality indicators i.e. low-mortality DRG and hospital standard mortality ratio (HSMR). In addition, morbidity and mortality meetings are held at a local level. Further, Quality Assurance Committees (QAC) identify common issues across the state to identify lessons learnt and/or recommendations for consideration statewide and locally. Other QACs e.g. Queensland Audit of Surgical Mortality provide individual feedback to practitioners to improve individual performance. |

Western Australia | WA does not report publicly on these data. WA Health currently reports six indicators internally that are based on the Core Hospital Based Outcome Indicator (CHBOI) specifications published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC); Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio, In‑hospital Mortality (for Stroke, Fractured Neck-of-Femur, Acute Myocardial Infarction and Pneumonia) and Death in Low Mortality Diagnosis-Related Groups. Outliers for these indicators are reviewed on a regular basis through the WA Health system Quality Surveillance Group (QSG). Note that the results of mortality reviews as undertaken by local Mortality Committees are publicly available from the annual WA Health Your safety in our hands in hospital patient safety report. |

South Australia | SA does not report publicly on these data. For internal mortality analysis, SA uses national Core hospital based outcome indicators (CHBOI) developed by the ACSQHC. Examples include: monitoring Hospital standardised mortality ratios (HSMR) (included as a key performance indicator in service agreements) and monitoring CHBOI condition-specific mortality measures (fractured neck of femur, stroke, AMI and pneumonia). |

Tasmania | Tasmania does not report publicly on these data. Tasmania uses Diagnosis Standardised Mortality Ratios as used by Health Round Table for reporting within hospitals (https://www.healthroundtable.org/Join-Us/Core-Services/Mortality-Comparisons). Tasmania also uses Core hospital-based outcome indicators of safety and quality (CHBOI). This reporting system has included in-hospital mortality and unplanned/unexpected hospital re-admissions, as developed by the ACSQHC. These indicators are designed as screening tools for internal safety and quality improvement, and they are not intended to be used as performance measures. |

Australian Capital Territory | The ACT does not report publicly on these data. Mortality information from Canberra Health Services (CHS) is collated by the Health Round Table (HRT) and includes deaths in low mortality DRGs and is defined by the ACSQHC and adopted by IHPA. These may not necessarily be avoidable when investigated. Sentinel events are reported to ACT Health Directorate for inclusion in IHPA reporting. There is no specific policy on the review of deaths though the CHS has an Incident Management Procedure. Mortality data published by HRT however is only available to the hospital concerned, and although benchmarking can occur sites are not identified. There is a formal death review committee that focuses on children and young people and another that focuses on maternal and perinatal deaths. The ACT Children and Young People Death Review Committee reviews all deaths of children and young people aged from birth to 18 years. This committee reports annually to the Minister for Children, Youth and Families and the statistics are published here: https://www.childdeathcommittee.act.gov.au/publications. The ACT Maternal and Perinatal Mortality Committee reviews all deaths of women who died while pregnant or up to 42 days post-partum and all deaths of fetuses from 20 weeks gestation and babies up to 28 days of life. Maternal death information is included in national reports but is not published specifically for the ACT due to the very small number of deaths in the ACT. The perinatal death rate is published annually here: https://health.act.gov.au/about-our-health-system/data-and-publications/healthstats/statistics-and-indicators/perinatal and a detailed report is provided by the Committee to the ACT Chief Health Officer and published every five years https://health.act.gov.au/about-our-health-system/data-and-publications/healthstats/epidemiology-publications. |

Northern Territory | The NT does not report publicly on these data. The NT uses national Core hospital based outcome indicators (CHBOIs) developed by the ACSQHC. CHBOI 1 - Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio (HSMR); CHBOI 2 - Death in low-mortality Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs); CHBOI 3: Condition Specific Mortality Measures. These data are included in the internal NT Health Patient Quality and Safety Surveillance Quarterly Report. The NT also provides data on coronial recommendations, Incident Severity Rating 1 events (ISR1s), and national sentinel events. |

Sources: State and Territory governments (unpublished).

Performance indicator data for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in this section are available in the data tables listed below. Further supporting information can be found in the 'Indicator results' tab and data tables.

| Table number | Table title |

|---|---|

| Table 12A.15 | Patients treated within national benchmarks for emergency department waiting time, by Indigenous status, by State and Territory |

| Table 12A.20 | Waiting times for elective surgery in public hospitals, by Indigenous status and procedure, by State and Territory (days) |

| Table 12A.34 | Patients who did not wait, left or were discharged against medical advice, by Indigenous status (public hospitals) |

| Table 12A.38 | Separations for falls resulting in patient harm in hospitals, per 1000 separations |

| Table 12A.46 | Unplanned hospital readmission rates, by Indigenous status, hospital peer group, remoteness and SEIFA IRSD quintiles |

Key terms

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

Accreditation | Professional recognition awarded to hospitals and other healthcare facilities that meet defined industry standards. Public hospitals can seek accreditation through the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program, the Australian Quality Council (now known as Business Excellence Australia), the Quality Improvement Council, the International Organisation for Standardization 9000 Quality Management System or other equivalent programs. |

Acute care | Clinical services provided to admitted patients, including managing labour, curing illness or treating injury, performing surgery, relieving symptoms and/or reducing the severity of illness or injury, and performing diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. |

Admitted patient | A patient who undergoes a hospital’s admission process to receive treatment and/or care. This treatment and/or care is provided over a period of time and can occur in hospital and/or in the person’s home (for hospital-in-the-home patients). |

Allied health (non‑admitted) | Occasions of service to non-admitted patients at units/clinics providing treatment/counselling to patients. These include units providing physiotherapy, speech therapy, family planning, dietary advice, optometry and occupational therapy. |

Australian classification of health interventions (ACHI) | Developed by the National Centre for Classification in Health, the ACHI comprises a tabular list of health interventions and an alphabetic index of health intervention. |

AR-DRG | Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Group - a patient classification system that hospitals use to match their patient services (hospital procedures and diagnoses) with their resource needs. AR-DRG version 6.0x is based on the ICD-10-AM classification. |

Casemix adjusted | Adjustment of data on cases treated to account for the number and type of cases. Cases are sorted by AR‑DRG into categories of patients with similar clinical conditions and requiring similar hospital services. Casemix adjustment is an important step to achieving comparable measures of efficiency across hospitals and jurisdictions. |

Casemix adjusted separations | The number of separations adjusted to account for differences across hospitals in the complexity of episodes of care. |

Community health services | Health services for individuals and groups delivered in a community setting, rather than via hospitals or private facilities. |

Comparability | Data are considered comparable if (subject to caveats) they can be used to inform an assessment of comparative performance. Typically, data are considered comparable when they are collected in the same way and in accordance with the same definitions. For comparable indicators or measures, significant differences in reported results allow an assessment of differences in performance, rather than being the result of anomalies in the data. |

Completeness | Data are considered complete if all required data are available for all jurisdictions that provide the service. |

Cost of capital | The return foregone on the next best investment, estimated at a rate of 8 per cent of the depreciated replacement value of buildings, equipment and land. Also called the ‘opportunity cost’ of capital. |

Elective surgery waiting times | Elective surgery waiting times are calculated by comparing the date on which patients are added to a waiting list with the date on which they are admitted for the awaited procedure. Days on which the patient was not ready for care are excluded. |

Emergency department waiting time to commencement of clinical care | The time elapsed for each patient from presentation to the emergency department (that is, the time at which the patient is clerically registered or triaged, whichever occurs earlier) to the commencement of service by a treating medical officer or nurse. |

Emergency department waiting times to admission | The time elapsed for each patient from presentation to the emergency department to admission to hospital. |

ICD-10-AM | The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems - 10th Revision - Australian modification (ICD-10-AM) is the current classification of diagnoses in Australia. |

Hospital boarder | A person who is receiving food and/or accommodation but for whom the hospital does not accept responsibility for treatment and/or care. |

Length of stay | For an episode of care, the period from admission to separation less any days spent away from the hospital (leave days). |

Medicare | Australian Government funding of private medical and optometrical services (under the Medicare Benefits Schedule). Sometimes defined to include other forms of Australian Government funding such as subsidisation of selected pharmaceuticals (under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) and public hospital funding (under the Australian Health Care Agreements), which provides public hospital services free of charge to public patients. |

Newborn qualification status | A newborn qualification status is assigned to each patient day within a newborn episode of care. A newborn patient day is qualified if the infant meets at least one of the following criteria:

A newborn patient day is unqualified if the infant does not meet any of the above criteria. The day on which a change in qualification status occurs is counted as a day of the new qualification status. If there is more than one qualification status in a single day, the day is counted as a day of the final qualification status for that day. |

Nursing and midwifery workforce | Registered nurses, enrolled nurses and midwives who are employed in nursing and/or midwifery in Australia excluding those on extended leave. |

Medical practitioner workforce | Registered medical practitioners who are employed in medicine in Australia excluding those on extended leave. |

Non-acute care | Includes maintenance care and newborn care (where the newborn does not require acute care). |

Non-admitted occasions of service | Occasion of examination, consultation, treatment or other service provided to a non-admitted patient in a functional unit of a health service establishment. Services can include emergency department visits, outpatient services (such as pathology, radiology and imaging, and allied health services, including speech therapy and family planning) and other services to non-admitted patients. Hospital non-admitted occasions of service are not yet recorded consistently across states and territories, and relative differences in the complexity of services provided are not yet documented. |

Non-admitted patient | A patient who has not undergone a formal admission process, but who may receive care through an emergency department, outpatient or other non-admitted service. |

Peer group(s) | Peer groups are used to categorise similar hospitals with shared characteristics. Categorising hospitals in peer groups allows for valid comparisons to be made across similar hospitals providing similar services. The peer groups are:

For further details on hospital peer groups, see AIHW (2015) Australian hospital peer groups , Health services series no. 66. Cat no. HSW 170. Canberra: AIHW (https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/79e7d756-7cfe-49bf-b8c0-0bbb0daa2430/14825.pdf.aspx?inline=true). |

Posthumous organ procurement | An activity undertaken by hospitals in which human tissue is procured for the purpose of transplantation from a donor who has been declared brain dead. |

Public hospital | A hospital that provides free treatment and accommodation to eligible admitted persons who elect to be treated as public patients. It also provides free services to eligible non-admitted patients and can provide (and charge for) treatment and accommodation services to private patients. Charges to non-admitted patients and admitted patients on discharge can be levied in accordance with the Australian Health Care Agreements (for example, aids and appliances). |

Real expenditure | Actual expenditure adjusted for changes in prices. |

Relative stay index | The actual number of patient days for acute care separations in selected AR–DRGs divided by the expected number of patient days adjusted for casemix. Includes acute care separations only. Excludes: patients who died or were transferred within 2 days of admission, or separations with length of stay greater than 120 days, AR-DRGs which are for ‘rehabilitation’, AR‑DRGs which are predominantly same day (such as R63Z chemotherapy and L61Z admit for renal dialysis), AR-DRGs which have a length of stay component in the definition, and error AR-DRGs. |

Same day patients | A patient whose admission date is the same as the separation date. |

Sentinel events | Adverse events that cause serious harm to patients and that have the potential to undermine public confidence in the healthcare system. |

Separation | A total hospital stay (from admission to discharge, transfer or death) or a portion of a hospital stay beginning or ending in a change in the type of care for an admitted patient (for example, acute to rehabilitation). Includes admitted patients who receive same day procedures (for example, dialysis). |

Service event | An interaction between one or more health-care provider(s) with one non-admitted patient, which must contain therapeutic/clinical content and result in dated entry in the patient’s medical record. |

Subacute care | Specialised multidisciplinary care in which the primary need for care is optimisation of the patient’s functioning and quality of life. A person’s functioning may relate to their whole body or a body part, the whole person, or the whole person in a social context, and to impairment of a body function or structure, activity limitation and/or participation restriction. Subacute care comprises the defined care types of rehabilitation, palliative care, geriatric evaluation and management and psychogeriatric care. |

Triage category | The urgency of the patient’s need for medical and nursing care: category 1 — resuscitation (immediate within seconds) category 2 — emergency (within 10 minutes) category 3 — urgent (within 30 minutes) category 4 — semi-urgent (within 60 minutes) category 5 — non-urgent (within 120 minutes). |

Urgency category for elective surgery | Category 1 patients — admission within 30 days is desirable for a condition that has the potential to deteriorate quickly to the point that it can become an emergency. Category 2 patients — admission within 90 days is desirable for a condition that is causing some pain, dysfunction or disability, but that is not likely to deteriorate quickly or become an emergency. Category 3 patients — admission at some time in the future is acceptable for a condition causing minimal or no pain, dysfunction or disability, that is unlikely to deteriorate quickly and that does not have the potential to become an emergency. |

References

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) 2020, Annual Report 2019‑20, ACSQHC, Sydney, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/acsqhc-annual-report-2019-20 (accessed 12 October 2021).

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2021, Hospital resources 2019‑20: Australian hospital statistics, Health services series, AIHW, Canberra, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/myhospitals/sectors/admitted-patients (Hospital resources 2019-20 data tables, accessed 12 October 2021).

—— 2021a, Admitted patient care 2019‑20: Australian hospital statistics, AIHW, Canberra, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/myhospitals/sectors/admitted-patients (accessed 12 October 2021).

—— 2021b, Non-admitted patient care 2019‑20: Australian hospital statistics, Health services series, AIHW, Canberra, https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports-data/myhospitals/sectors/non-admitted-patients (accessed 12 October 2021).

Montalto, M., McElduff, P. and Hardy, K. 2020, 'Home ward bound: features of hospital in the home use by major Australian hospitals, 2011–2017', Medical journal of Australia, vol 213, no. 1, pp. 22-27.

Download supporting material

- 12 Public hospitals data tables (XLSX - 740 Kb)

- 12 Public hospitals dataset (CSV - 2668 Kb)

See the corresponding table number in the data tables for detailed definitions, caveats, footnotes and data source(s).