Economics of working from home

Speech

Chair Michael Brennan spoke at a Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) panel discussion on 12 October 2021.

Download the speech

Read the speech

Thanks for having me here to discuss our recent research on Working from Home.

Working from home is a highly topical issue, because so many have been forced to try it, and so much has been written – from differing perspectives – about whether it will or should continue.

It is also fascinating from an economic perspective for a number of reasons.

First, although our work emphasised the role of the ‘forced experiment’ brought about by COVID, it is important to remember that there is an underlying relative price effect that has made remote working more feasible and attractive.

As I never tire of reminding people, the central workplace is a relatively recent phenomenon in human history, and it was aided by the rapid falls in the real cost of moving people from place to place.

For much of the 20th century, transport became faster, cheaper and better. Efforts at futurism reflected that too – I have talked elsewhere about the US Postmaster General in the 1950s who predicted the advent of rocket mail.

George Jetson – that futuristic figure who first appeared in the 1960s – drove around in a space car in a space city. But he still drove to work.

It is a reminder that in our long-range predictions we so often get it wrong because we extrapolate along a single dimension – an observation made by Australian tech investor Rodney Brooks.

For the last three decades, moving people has not become much faster or much easier, particularly with congestion in major cities. Cars are cheaper, but the time cost of the commute is going up. Because of its service element, underlying public transport costs also tend to rise faster than overall inflation.

But the cost of computing, information technology and communications has plummeted.

In much of the debate over the pros and cons of remote work, we often forget that there is a fundamental technological shift – some underlying tectonic forces at work.

Second, it is interesting that despite this relative cost shift, the level of working from home hardly budged for the last 20 years – HILDA suggests 8 per cent of employees did it some of the time; we estimate that translated into about 2 per cent of hours worked; on Census day around 5 per cent of workers did not commute to work.

Those levels have stayed fairly constant since 2000.

And then the pandemic came along and changed everything, not least of which was the perception of working from home.

It seems to contradict the traditional micro-economic assumption of rational profit maximising firms and utility maximising households, all operating on the basis of known, fixed preferences and complete knowledge.

There shouldn’t be $100 bills on the sidewalk, and yet prior to 2020 there was clearly some untapped potential for more employees to work effectively from home and for employers to allow it. Why didn’t they?

Economists have made a few observations about this:

- Before the pandemic, the pay-offs for a firm to experiment with work from home were asymmetric: if it went well, others might copy. If it was a disaster, then that would be, well, disastrous. So it was safer not to.

- There is something akin to multiple equilibria when it comes to perceptions of working from home. Before COVID, work from home had a stigma – was it working from home, or shirking from home? In that world, industrious, productive employees might shy away from seeking remote work because of what it might signal about their work ethic. So the stigma can become self-reinforcing (a stable equilibrium). COVID removed the stigma by requiring large numbers to work from home irrespective of their relative work ethic.

- The assumption of profit maximisation with complete information has always been a very imperfect representation of how business decisions are made, particularly in the context of new technologies. This is an observation made by Armen Alchian in his 1950 classic Uncertainty, Evolution and Economic Theory.

The point about experimentation is that it leads to learning. The forced experiment of COVID was no exception. It appears that firms and workers learned two things:

- They learned something about where they sat in the productivity distribution of remote work across firm/workers pairings

- They learned that the mean of that distribution was a bit higher / better / more productive than they would have thought in 2019.

For many, that was a double whammy, creating a strong upside surprise.

Another reflection is that the forced experiment of the pandemic was just the beginning. As restrictions ease, we will observe a second wave of experimentation.

This time, instead of everyone doing the same thing, firms and workers will be trying out almost endless different and individualised approaches and learning from that experience. Fully remote, fully centralised and all the possible versions of the hybrid model.

The learning from this second experiment comes in two forms – the conscious learning that comes from firms identifying what works and doesn’t work for them, as well as the unconscious learning that happens at the level of the economy as a whole, as successful models are rewarded by survival and expansion while unsuccessful models fall by the wayside.

Despite the traditional economic affection for representative agent models (like the single representative firm or household – more on that later) the truth is that the economy relies on the sheer variety of models put forward in this second wave of experimentation. This variety facilitates the learning process – precisely because of the uncertainties and lack of knowledge faced by workers and firms.

The Productivity Commission is an evidence-based organisation, but to say much of interest about work from home one has to supplement evidence with judgement. The evidence just isn’t there yet, at least not in a definitive form.

We estimate that 35 per cent of jobs can be done from home. Few of those will be done exclusively from home, as they are in occupations and sectors that benefit from in person contact to stimulate collaboration and creativity.

So we sketched out a couple of scenarios: if all those who could work from home did so 2 days a week on average (1 day for part timers), we would see the number of hours worked from home rise to around 13 per cent.

Perhaps a more plausible assumption would be that only half of those who can work from home do so any of the time – again 2 days per week and 1 day for part timers. That would imply more like 7 per cent of hours worked from home.

It is still a big change – if for example the number of hours worked went from 2 per cent to 7 per cent and the number of people working from home some of the time rose to about 1 in 5.

It would represent a stark increase in a short space of time – much more rapid than other big changes like the rise of female participation or the rise of service sector employment, both of which have been dramatic but relatively gradual.

Will it hurt productivity?

Most of the public and media debate about the productivity of working from home is focused on the experience of individuals – often on the observation that some people are not particularly productive working at home.

By contrast, we were trying to answer a different question: namely, what happens at the economy wide level if an extra (say) 5, or even 10, percentage points of hours worked is worked from home?

In taking a sanguine view on that, in effect we are judging that the extra hours of remote work are coming disproportionately from the right-hand side of the distribution (those who do it better than average), or at worst a random draw. In other words, the extra hours worked from home are likely to be in those firms and by those workers and on those days where it can be done without diminution of productivity (and possibly with increased productivity).

And that can be true even if some individuals are less productive. The average effect is likely to be neutral or positive for a number of reasons: first, bosses have to agree to their employees working from home and they are unlikely to agree to a productivity-sapping arrangement. Also, the first day at home is likely to be more productive than the third, fourth or fifth (and an incremental 5 percentage points of remote work must come disproportionately from first days rather than fourth or fifth days). Finally, employees who want most to work from home have a very strong incentive to find employers and jobs where this can be done without loss of productivity and wages.

We are similarly positive about cities. Again, there is the tendency for some to extrapolate on a single dimension – more remote work means less work in the CBD, office vacancies will rise, cafes and restaurants will suffer, people will move further away from city centres and these trends will all become self-reinforcing.

In theory all those things are possible if the shock is big enough. Through history and across the world, cities have hollowed out or at least taken a long time to recover from a big shock.

Our judgement is that the shock here is not big enough. And for smaller shocks, the second-round effects tend to mitigate, rather than amplify, the initial impact. So, for example, if office vacancies did increase, we would expect rents to fall. That makes it more attractive for new businesses to locate centrally.

If people commute less often, and trade this off against a longer trip when they do, then it’s possible that more jobs concentrate in the CBD rather than less.

These things are all speculative, but the broad point is that there is significant adaptive capacity in our cities – they are complex systems and they adjust on multiple margins.

One policy implication is that the case for more flexible regulation of land use gets stronger.

Planning is naturally controversial because of strong community interest in issues of built form. But we have over-planned and over-regulated land use. In a world of significant uncertainty, we still have planning systems that purport to determine – at very high levels of resolution – what forms of economic activity can occur where.

Most jurisdictions in Australia have multiple different commercial and business zones for different types of activity.

But do this thought experiment. Imagine someone sitting in their home office, ordering some groceries online between meetings and then ordering some new office equipment for the home set-up.

All those land uses – office, residential, supermarkets and large format retail – have separate zonings in the physical world of land use planning. But surely in light of the dramatic changes we are seeing through remote work and online retail, we have to be open to new, novel combinations and co-locations of these things.

The boundary between retail and industrial zonings (e.g. fulfillment centres) is already becoming blurred – except in planning schemes, where retail and industrial zonings are quite distinct.

The workplace relations system is another policy framework that has been tested by remote work – not just because the regulation of hours of work is based on presence in a physical workplace. During the pandemic, the system showed itself to be quite adaptive in giving businesses and workers the flexibility to undertake work outside the ‘standard workday’ or require workers to perform different duties.

Many of the occupations and sectors most likely to work from home have less contact with the formal workplace relations (WR) system – they tend not to be award reliant, are paid well above statutory minima and often work flexible hours. Many of them would be on formal enterprise agreements, however.

The challenge for the WR system is that the preferences for, and feasibility of, working from home is quite individual, whereas the system is largely based on collective entitlements – the National Employment Standards (NES) enshrine mandatory community-wide minima; awards operate across industries and collective agreements across a business or worksite. It is very hard for any of these instruments to enshrine a substantive right to work from home because a collective, one-size-fits all entitlement is unlikely to be appropriate.

So firm policies and individual arrangements are most likely to be the mechanisms used to give effect to work from home. The NES and some awards do enshrine certain procedural entitlements – like the right to request remote work for certain classes of employees – but these stop short of substantive entitlements.

A contextual issue is that – in general – workers appear to desire the ability to work from home more than bosses want to extend it, largely because the main benefit is the commute avoided, and this is hard for the employer to monetise.

So employer representatives tend to voice some caution about work from home – both its productivity impact and the implications for areas like work health and safety. But many commentators also worry about work from home from an employee perspective – particularly the concern as to whether it might lead to more contracting and insecure work.

So if we imagine the WR system as being there, in part, to protect workers against harms, we first have to work out which harms matter more – not enough working from home or too much of it. The system can do both, but realistically only through procedural rules, like the right to request and the obligation on employers to consult about major workplace changes, rather than providing a substantive entitlement to work from home or to work from a central location.

Following on from the publication of our report a few weeks ago, we have also published on our website what we describe as a ‘simple model’ of working from home. We used this model as scaffolding – not so much to tell us ‘the answer’ but to help us think through how the bargain between employer and employee might work out and what variables would shape it.

I guess it’s simple in two ways: one, that it makes a lot of simplifying assumptions – a single representative firm, a single representative individual, both maximising profit and utility with well-defined production and utility functions. Both are price takers. The usual things.

Second, it doesn’t rely on overly complex mathematical methods. It’s a standard ‘constrained optimisation’.

But a quick look at the paper will show that it’s not that simple. There are complicated looking equations everywhere. The functional form and the first order conditions get quite long and complicated because we have to add new terms to try and capture what is going on when we add working from home to a more standard model.

To start from the beginning, a standard model of the household’s decision to work involves them trading off consumption (the fruits of paid work) and leisure – two goods which increase utility. The assumption is that no one would want to work except for the pay – the consumption it makes possible. So households choose a level of labour (to pay for consumption) and leisure.

To capture working from home, we add two types of labour – work in the office and work at home – into the utility function. Both forms of labour provide some benefit to the household: working from the office has the benefit of sociability; working from home provides some flexibility (e.g. to combine work with other domestic priorities).

This has two effects. One is that it means labour is now entering the utility function explicitly. It is no longer just the opposite of leisure. This implicitly brings in the notion that workers are getting some positive utility from work, over and above the consumption it makes possible. That is contrary to the standard economic assumption, but as an approximation of the real world it’s not completely crazy. Many people do derive considerable intrinsic benefit from various forms of labour.

But it does mean that when it comes time to put (hypothetical) parameters into the model, you have to make sure the utility from these two types of labour isn’t too large, or your household becomes a complete workaholic. It has to be the case that consumption and leisure still dominate the overall labour supply choice.

Nonetheless, what the model shows is that the ability to work from home does generally increase the household’s labour supply. Much of that is because of the avoidance of the commute, which provides more time for workers to allocate between leisure and work.

Then there is another subtlety, which is the second effect of bringing two types of labour into the utility function. It is that the two types of labour in the utility function have a degree of complementarity. It is as though workers prefer variety rather than working all the time in one setting. This effect is small, compared with the role of the commute (partly because of the illustrative parameter values we have assigned in our simulation) but it does mean that when work from home becomes an option, there is a small labour supply effect purely because workers get higher marginal utility from an extra hour of work now that they are splitting their work across two locations rather than one. So in our simulation, you notice there is a (small) positive labour supply effect even for a worker with a hypothetical zero commute.

Again, this seems like a quirk of the model but not entirely crazy. Isn’t there something in the attraction to the hybrid model that comes from having a change of scene – that would translate into working longer on my first day at home than I would on my fifth day in the office? And it is consistent with survey evidence that shows that most workers want a hybrid of working from home and the office.

As I mentioned before, the model is based on representative agents, maximising known objective functions and taking wages as given. And the model is static. We observe the change in behaviour once work from home becomes possible by comparing outcomes in one model specification to those in another. It is a comparative static exercise.

These seem like significant limitations, given we are in a world that is changing and adapting to a new way of working in the face of great uncertainty. But it can still yield insights into the forces that might shape the adjustment.

For example, one obvious point borne out in the model is that it involves two types of labour (at home and at the central location) but usually there will only be one wage. Assuming the employer cannot pay differential wages for different locations of work, they are constrained in their choice as to how much working from home they will want to offer – there is a unique point where the marginal product of labour is the same for each type of labour.

It is highly unlikely that this point will match the relative preference of the household. This creates a natural tension in the relationship. You can imagine three ways in which it might be resolved:

- The employer might find other ways of improving the relative attractiveness of working in the central location to shape worker preferences, such as through ways to foster greater social interaction in the office.

- Labour will reallocate over time, so that workers with a high preference for working from home seek out employers and workplaces where working from home is more productive.

- Even if workers stay put, there is incentive for them to demonstrate higher productivity when working at home, to shift their employer’s preferences into greater alignment with their own.

All of these things reflect the possible ways in which a market economy can adapt to a change like this. It reminds us that there are huge incentives to share the gains that this technology makes possible and to get better at using it over time. This is part of the reason we are cautiously positive about the overall impact of working from home across the economy as a whole.

Speech

Chair Danielle Wood presented to the National Conference on University Governance.

Download the speech

Read the speech

Thank you everyone for the opportunity to speak tonight. I am honoured to stand on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation and I pay my respect their elders past and present. I extend that respect to any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the audience today.

I’m sure it’s something of a cruel and unusual punishment making you sit through a speech on productivity before you get your dessert. I hope I can convince you that productivity is its own treat, and a substantial one at that. As the Nobel Prize winning economist Robert Lucas said: ‘Once one starts to think about [economic growth], it is hard to think about anything else.’ 1

But beyond (hopefully) convincing you that productivity matters, I want to focus on the unique role of universities as engines of productivity. And I will issue a challenge: for universities to step up their own productivity performance so as to deliver more of the research and quality teaching Australia needs for us to thrive in coming decades.

Productivity – why do we care?

Productivity is about improving our living standards. If we can produce more goods and services using the same or fewer resources than before, that’s productivity growth.

And the effects of that growth over time are enormous.

In 1901 in Australia, it took 18 minutes of the average worker’s time to afford a standard loaf of bread. Today, it is just 4 minutes.’ 2

The productivity of our bread makers means that we can all consume a lot more bread – or for the carb conscious – spend that extra bread money elsewhere.

But it’s not just bread production that’s been revolutionised.

A theatre ticket cost an average worker 321 minutes of work in 1901. Today it’s 62. A bicycle? 473 hours in 1901 down to just 6 hours today.

And to put even today’s very real concerns about rental costs into perspective: the typical Australian worked 9 hours a week to afford a rental in 2019 but 20 hours in 1901.

Wherever you look, productivity progress has improved our capacity to deliver the goods and services that we value.

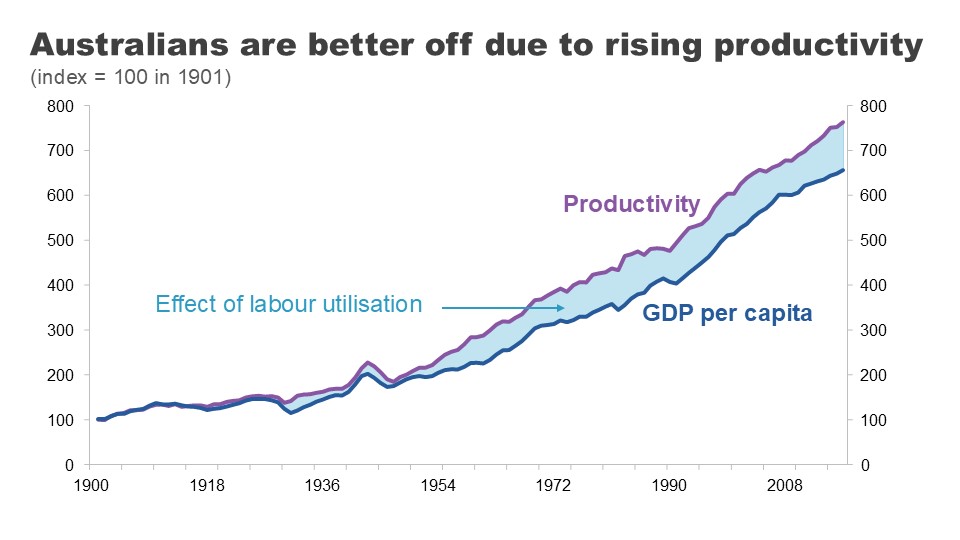

That productivity growth has seen real per person incomes improve by more than 700% since Federation, while giving us an extra 13 hours a week to ourselves.’ 3

But here let me engage with a common argument dismissing the importance of productivity. According to the doubters, this economic growth might deliver more ‘stuff’ but does not deliver better lives or improved wellbeing.

I would mostly disagree. It is certainly true that economic growth won’t tuck your kids into bed at night, but it has delivered at lot more than just extra bread or bicycles.

Growth is correlated with so many of the things we care about: longer, healthier lives, better education, more and more varied leisure time, and better and more stable political institutions.

Many of these things are supported by growth but they also support growth themselves. As I’ll explain shortly, this is very much the case with education.’ 4

That’s why it’s not surprising that richer countries tend to have higher average life satisfaction’ 5 and that those countries that experience sustained economic growth tend to see their average levels of satisfaction increase over time.’ 6

That said, economists recognise that growth is not a measure of everything we care about. Some things are hard to measure well, like the quality of care services. And important determinants of wellbeing like community involvement and quality of relationships are missed all together.

But no one can or should deny that growth matters.

Houston, we have a (productivity) problem

I don’t need to tell this audience that Australia’s recent productivity performance hasn’t been much cause for celebration.

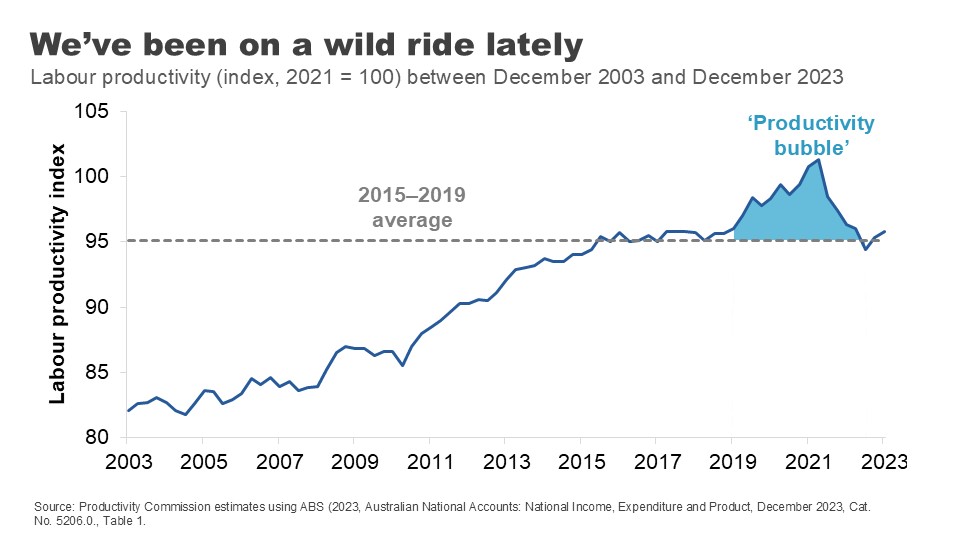

Productivity went on a roller coaster ride during COVID.

In the first two years of the pandemic, productivity rose strongly. This counterintuitive result was primarily because social distancing restrictions reduced hours worked the most in the lower-productivity services sectors.

But this productivity ‘bubble’ was in no way sustainable. After the end of restrictions in 2022, working hours expanded again in these sectors and pushed productivity in the opposite direction. The bubble burst.

The strong performance of the labour market through much of 2022 and 2023 has also put downward pressure on productivity during this period.

Now let me be totally clear: strong labour markets are great. But the surge in hours worked in the COVID recovery (coming from increased participation, lower unemployment and the re-opening of borders) was both quick and large. The capital stock has not kept up. The historical decline in the amount of capital per worker, has dragged on productivity because each worker has less capital – fewer or less efficient tools and resources – to help them do their jobs.’ 7

In some ways, the economy is like the cobra swallowing the ‘rat’ of the COVID shock. It will digest it, but it will take some time.

But this begs the question: what is the economy recovering to?

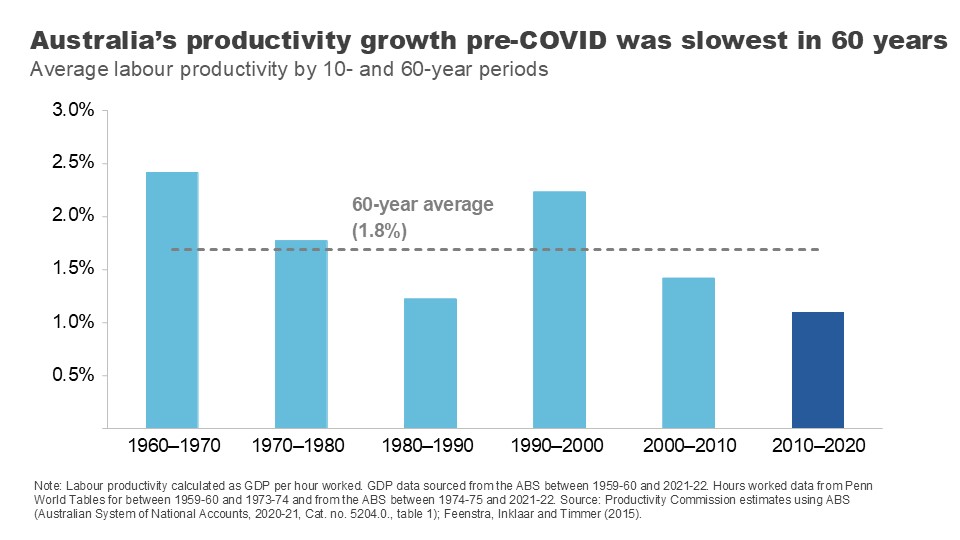

Even before our COVID rollercoaster, all was not well.

In the decade sandwiched between the GFC and COVID, Australia’s annual productivity growth averaged just 1.1% – the lowest of the last 6 decades and well below its 60-year average.

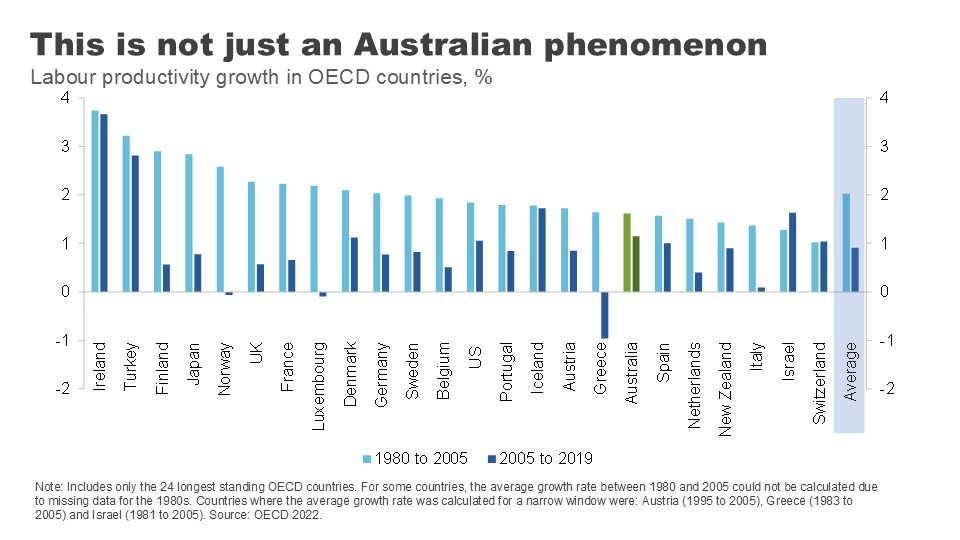

This slowdown in productivity growth is not just an Australian phenomenon.

Almost every OECD country experienced a substantial decline in labour productivity in the 15 years prior to COVID, compared to the previous 15. Across the OECD, labour productivity growth halved in this period.

A range of credible explanations have been put forward to explain why: growth in the lower productivity services sector, declining gains from education, a smaller contribution from technological change, reduced economic dynamism, and increased risk aversion by business and capital owners.

But what I want to focus on here are two that are most relevant to our universities: declining gains from education and declining contribution from innovation. And then I want to address how the people in this room can help turn them around.

Universities are a powerful engine for productivity

Universities contribute a huge amount to our intellectual, social and cultural lives. But you’ve an invited an economist tonight so I’m naturally going to talk about the ways in which universities contribute to our long-term productivity performance.

There are, I think, three major channels:

- through building the skills and capacity of our future workforce – the so called ‘human capital’ of our population

- by generating and disseminating the research and ideas that lead to better processes and new and improved goods and services, and

- through building ties, understanding and goodwill with people from other nations, which contributes to ongoing integration – whether through trade, investment or the flow of ideas.

Tonight, I’m going to focus on the first two.

Boosting human capital

Let me start with the fundamental role that universities play in educating the population.

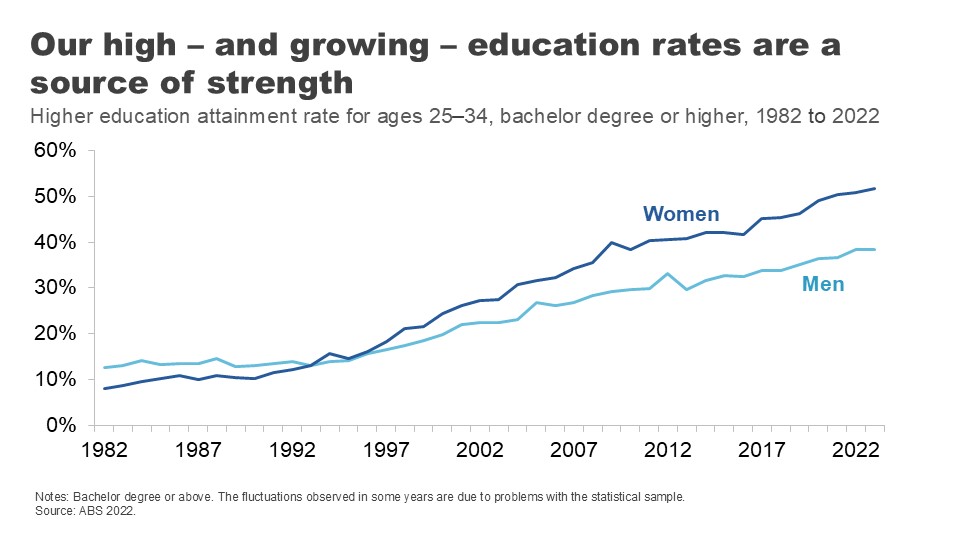

In the past 30 years, education levels across the Australian population have soared.

In the early 1980s, about one in ten 25–34-year-olds had a held a university qualification. Today, it’s 45%.’ 8

Part of this increase has been driven by a strong migration program that has encouraged skilled migrants to settle on our shores.’ 9 But it points as well to a large and sustained expansion in the number of Australians going to university.

Annual domestic student course completions have more than doubled since 1989, with nearly 140,000 students finishing a bachelor’s degree in 2021 and 87,000 finishing post-graduate study.’ 10

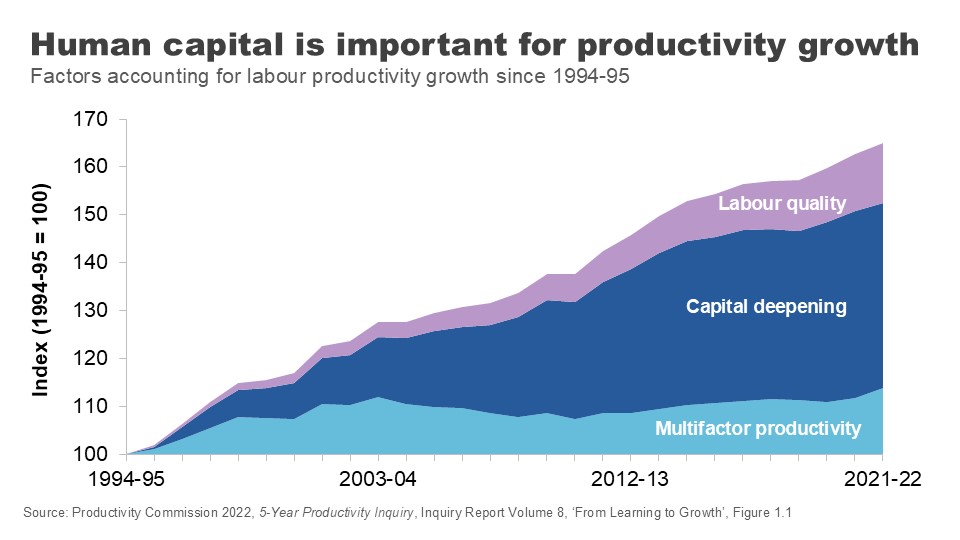

The resultant improvement in ‘labour quality’ has played an important role in productivity growth – particularly as other contributors have stalled.

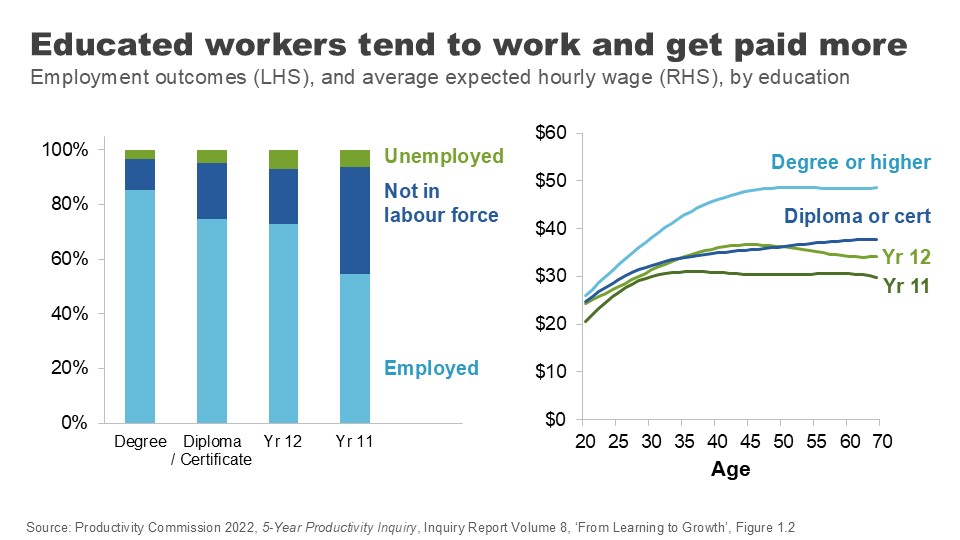

University degrees are associated with better employment outcomes and higher earnings over people’s lifetimes – even after adjusting for individuals’ characteristics.’ 11

Although the graduate premium is in decline,’ 12 it is still significant across the lifetime.

Higher levels of education in our working population improves wages and productivity through a few channels.

Most obviously, it improves the skills and abilities of our future workforce.

People who hold a tertiary qualification have higher cognitive performance than others their own age, even when you control for the fact that clever people tend to go on to study at higher levels. 13

Perhaps just as importantly, people with a higher education are more likely to do on-the-job training when they’re in the workforce – they’ve learned how to learn. 14 And there’s evidence going to university improves your non-cognitive skills, like sociability and your ability to cooperate or work in a team. 15

Education also improves people’s capacity to innovate. Increases in the supply of educated workers and managers leads to greater direct innovation by firms. Those educated workers are also more likely to adopt new innovations from elsewhere. 16

This link between education and an innovation mindset is critical if we are to supercharge the productivity upside from education, a point I will return to.

There are still gains to be eked out from expanding Australians’ access to higher education, despite the huge expansion over recent decades.

As the Productivity Commission noted in our 2023 Productivity inquiry, there is no evidence that we have reached the point where the cost of education for marginal workers outweighs the benefit received by them and by society. 17

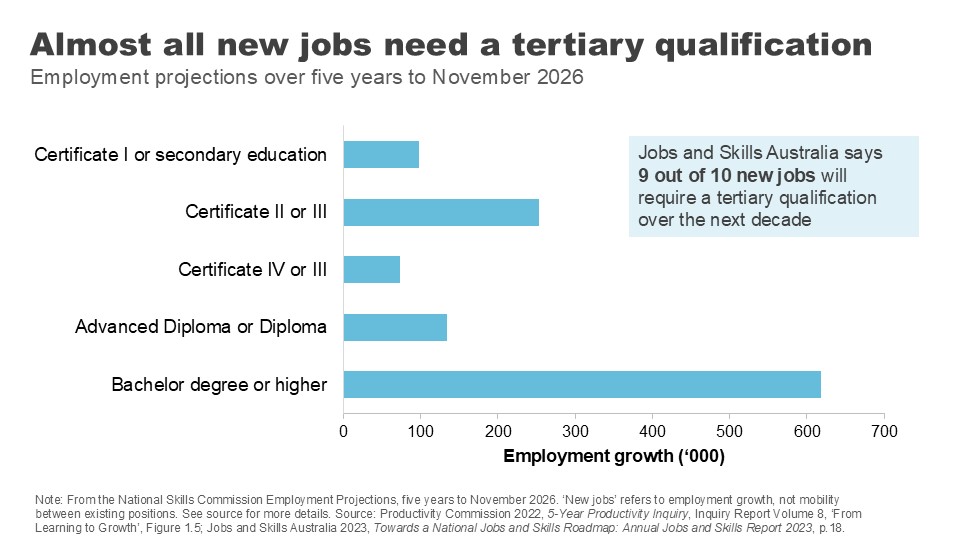

According to Jobs and Skills Australia, more than 9 out of 10 new jobs will require a post-school qualification over the next decade, and around 50% will require a bachelor's degree. 18

The recent Universities Accord argued governments should continue to promote participation in university and vocational education and set ambitious targets for governments to boost attainment rates by 2050.

The benefits of higher education are why the PC has supported a return to a system of uncapped demand driven funding. 19

But even with this potential upside, the huge ramp up in the education levels of the population will not be repeated. This means the contribution of gains from the quantity of education in the productivity numbers is likely to be more subdued in coming decades than in the previous ones.

This brings the quality of education into even sharper focus.

Education quality: levelling up

Improving education quality means improving outcomes for students for a given level of investment.

Which begs the question: how are we currently faring?

As already mentioned, university graduates have good labour market outcomes over the medium term compared with those who acquire skills via VET or school alone, even after adjusting for student characteristics.

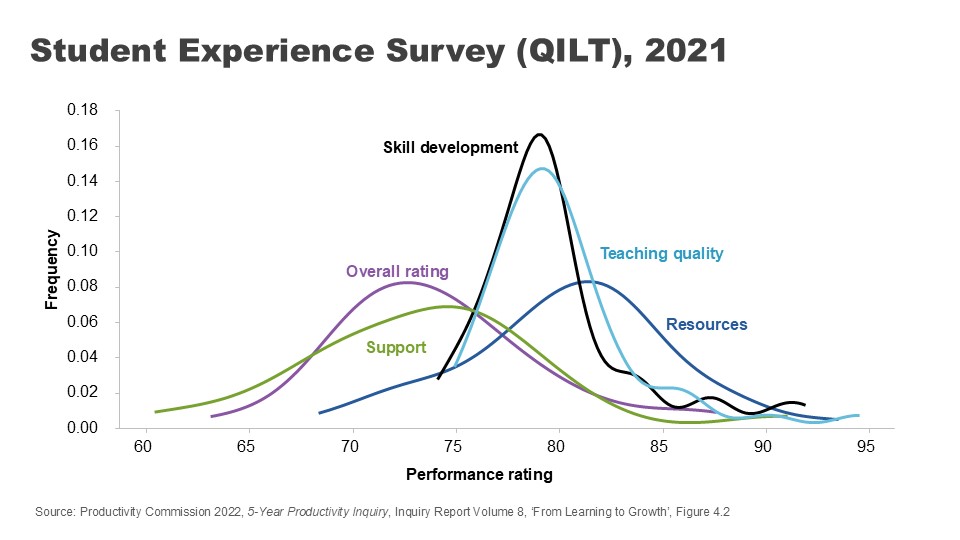

Australian universities also perform well overall on student-assessed measures of quality. Indeed, the average university brings home a 76% – just scraping through with a distinction – on overall experience for undergraduate students. 20 On assessed teaching quality, it’s 80% – a solid mark. 21

Further, on measures of employer satisfaction, overall satisfaction with graduates sits just below 84% and has remained strong over time. 22

But there are reasons to be vigilant.

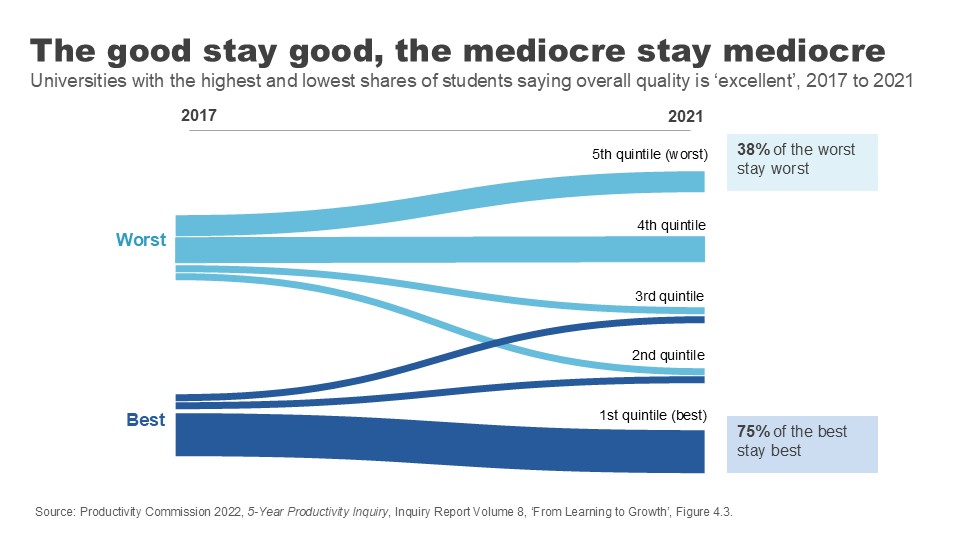

Despite the relatively strong average student-assessed quality scores, there is a fair degree of variation across institutions.

There is also stickiness in the outcomes data, suggesting a lack of course correction. Measured over a 4-year period, the universities that start with the highest share of students nominating their quality as ‘excellent’ tend to stay excellent, while those with the lowest shares also tend to stay at the bottom.

Employer satisfaction scores, while high overall, are stronger for foundational and technical skills than broader job skills like collaboration and adaptation. 23

And employers report much lower levels of satisfaction with the collaboration skills of graduates who study entirely remotely. 24 This matters because these ‘social skills’ are increasingly demanded by employers as a complement to technical skills. 25

More generally we need to consider the impact of online course delivery for student learning. The shift to online adds convenience and flexibility for students, but it comes with risk to quality.

Measures of learning engagement dropped when the pandemic hit our shores, and have not recovered since. 26

We may have jumped many of the initial hurdles to hybrid learning during those chaotic months of shutdowns, but not everyone has yet nailed the challenge of how to do online delivery well. A sea of blank Zoom screens is not ideal for either students or teachers.

More broadly, the Productivity Commission has noted the lack of direct incentive for teachers and universities to improve teacher quality.

We’re used to looking at star ratings when we book a hotel or a restaurant, but prospective students often don’t have good data when choosing between courses. 27

This lack of visibility combines with other factors – a general sense that teaching hold less prestige than research, government funding settings that fail to reward quality, and a lack of external oversight – to weaken the incentives for delivering the best teaching. 28

Of course, there are non-pecuniary incentives for individuals and institutions to teach well. And indeed, intrinsic motivations for excellence continue to steward high quality and innovative teaching practices at our universities.

But that is not enough to ensure that every teacher is delivering at a high standard.

The PC has put forward a range of recommendations for change. An important one is making lecture and course materials publicly available. Letting the public see behind your high walls would sharpen the incentives for quality teaching, allow students to make better decisions around what courses might match their interests and assist in lifetime learning – giving those not looking for an accreditation access to an endless supply of learning opportunities. 29

We need to ensure that teaching excellence is at the heart of our universities if we are going sustain the big improvements in quality needed for future productivity gains.

Promoting innovation

I want to turn now to another critical way in which universities impact our prosperity – in their role as vectors for innovation.

It is technological change that drives most productivity improvements over time. 30 And it is ideas that make technological change possible.

Economics Professor Daniel Susskind has argued that asking ‘how do we generate more growth?’ is essentially the same as asking ‘how do we generate more ideas?’.

And what are universities if not factories for ideas? 31

It is worth remembering that when we talk about ideas we are not just talking about the novel, frontier research that some of your researchers might be engaged in. ‘New to the world innovation’ is only around 1-2% of Australia’s innovation story. Diffusion – the application of existing knowledge to different businesses and contexts – is a crucial part of the innovation puzzle. 32

‘Innovation for the 98%’ must also be a focus of research efforts and graduate skills sets.

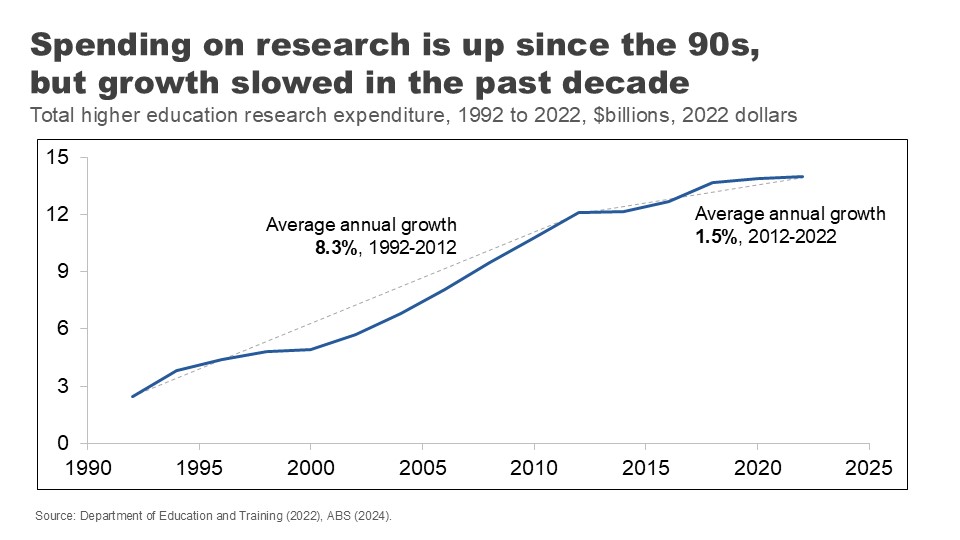

Universities spend more than they used to on research activity. Total university research expenditure has increased five-fold since the early 1990s – although growth has slowed somewhat in recent years.

This ramp up in spending over the past three decades is repeated across much of the developed world. But it has not generated the ideas boom we might have hoped.

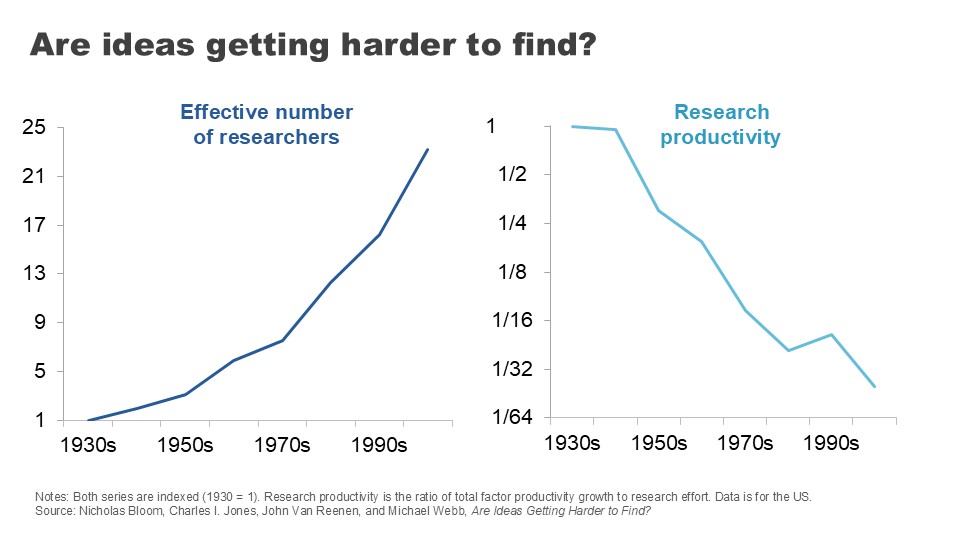

For example, if we turn to the US, we can see the number of people employed in research roles has grown 23-fold since the 1930s – a huge expansion in research effort. 33

But measured by the economic outputs of this research – the expansion in total factor productivity across the economy – the productivity of that research has declined 41-fold – or a growth rate of minus 5.1% per year on average. 34

This tale of more and more effort and for less and less return has played out across a range of innovation areas.

Take Moore’s Law: the tendency for the number of transistors fitted onto an integrated circuit to double every two years. It is, on the face of it, a remarkable testament to our capacity for innovation. But the number of researchers required to bring about this result has grown to be 18 times higher than it was in 1971. 35

Agricultural crop yields are improving at a relatively constant or slightly declining rate, but the number of agricultural researchers required to achieve this has doubled. 36

In drug discovery, the number of new drugs approved per billion on R&D halves every nine years or so, in a phenomenon that has been dubbed ‘Eroom’s Law’: Moore’s law spelled backwards. 37

At the heart of the slowdown in research productivity is that researchers inevitably solve the easier problems first – making gains harder once the lowest hanging fruit has been picked. Indeed, being ‘Better than the Beatles’ is a challenge that confounds across so many research areas. 38

But even noting this difficulty, there is still scope to improve the productivity of the research process in ways that could help generate and diffuse new ideas.

Australia is unusual in that university-led research makes up a relatively large percentage of our R&D expenditure. 39

As a share of GDP, our universities chip in more for research and development than universities in the US and Korea, and we’re well above the OECD average. 40

The good news is that our university research is top notch on academic metrics.

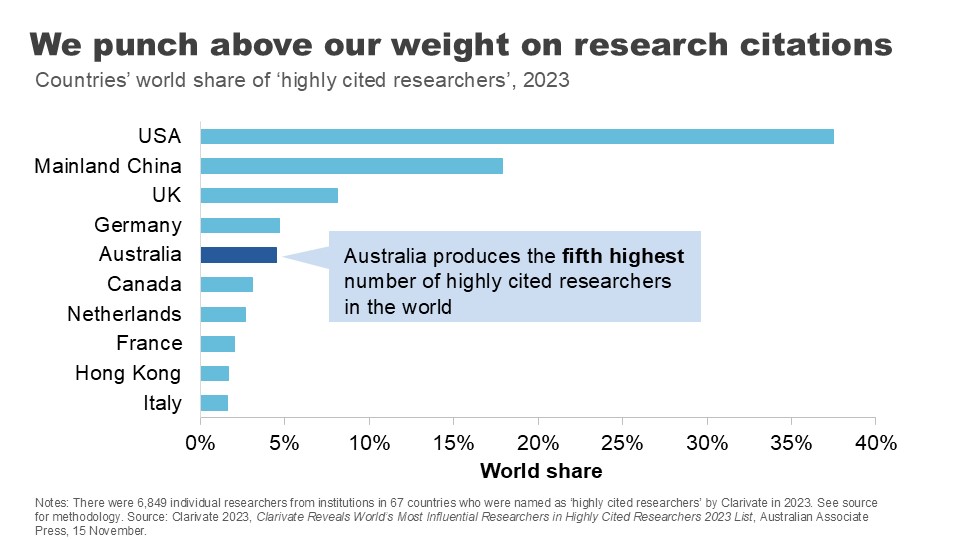

Despite our small population, we have the fifth highest number of highly citied researchers in the world. 41 And 84% of our research is rated at or above world standard. 42

Australian researchers also are more likely than those in the US or the EU to collaborate with international scholars, allowing us to ‘hoover up’ good ideas from overseas and apply them at home. 43

But there’s more we need to do.

There is a widely held view that Australian business collaboration with universities is poor. The perception is backed up in the numbers: data from the ABS suggests less than 10% of innovating firms got their ideas from universities between 2019 and 2021. 44

As much as policy makers say they want universities and business to ‘talk more’, clearly the incentives aren’t there to bring everyone to the table.

The Accord recognised the importance of nationally-relevant research in its recommendation for a new ‘Solving Australian Challenges Fund’ which would reward universities that apply their research capabilities to meeting Australia’s ‘big national challenges’. 45

Even where research turns up potentially useful ideas for Australian businesses or policy makers, we could do more to put them into practice.

Governments have long grappled with reducing barriers to research commercialisation – such as IP licencing and academic-spin offs or joint ventures – only partially successfully.

But the PC’s found we should be doing more to encourage knowledge transfers by encouraging labour mobility between industry and academia, and even by promoting joint conferences and networking events.

We can also help businesses tap into the experience and knowledge of academic researchers by reducing barriers to academic consulting, which is too often held up by administrative roadblocks. 46

There is also more to do on the productivity of the ideas generation process itself.

Long and expensive processes for grants can reduce ‘bang for buck’ and slow the research process.

US research on the peer-reviewed grant-making process concluded that the ‘tax’ of application processes may be up to 45% of researcher time. Further, these processes can skew or bias research efforts in a number of ways: towards more incremental research with a higher likelihood of surviving review than riskier or novel research; against interdisciplinary research; and towards researchers with a history of successful applications. 47

Certainly it does not take long for a conversation with Australian academics to degenerate into a similar set of complaints.

The recent Accord process suggested universities be paid for the indirect costs of applying for nationally competitive research grants, 48 and the Australian Research Council recently took the positive step of introducing an Expression of Interest round to its Discovery grant applications. 49

Future work may be necessary to explore alternative models like ‘science lotteries’ to continue tackling these challenges. 50

Where to from here?

I realise tonight I am speaking to a sector working through significant upheaval.

The COVID shock – the rollercoaster ride of closing and then reopening international borders with flow on effects for international student numbers – was obviously hugely challenging. Universities are on the frontline of a major technological change with the shift to online teaching and the growing adoption of generative AI in both learning and research.

Those challenges have been amplified by big and disruptive policy changes over a short period: first with the Jobs Ready Graduates package, then a suite of regulatory reforms to student migration settings, 51 and now the proposal for international student caps.

The Universities Accord process, a generally more constructive policy exercise, is also starting to flow through to policy. But it has raised fundamental questions about the university business model and the extent to which we can continue to rely on international student revenue to ‘cross subsidise’ research activity.

I am here tonight to say the payoff from getting the policy settings and the internal culture right are high. Universities hold in their hands two crucially important ingredients for national productivity: the skills of our labour force and the generation and diffusion of ideas.

Gains in both of these areas are becoming harder to come by. That might naturally push you to look for more resources. But I’m here to encourage you to also look for improvements via productivity at home.

Promoting teaching excellence, widely sharing learning, supporting research with Australian impacts and empowering students with an innovation mindset are just some of the ways in which Australia’s universities can shape a more productive future for Australia.

Footnotes

- Lucas RE Jr 1988, On the mechanics of economic development, Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 22, Issue 1, p.5. Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: Keys to growth, Vol. 2, Inquiry Report no. 100, Canberra, p. 6. Return to text

- Ibid., p.17. Return to text

- Susskind D 2024, Growth: A Reckoning, Penguin Books, United Kingdom. Return to text

- Sacks, D, Stevenson, B & Wolfers, J 2010, Subjective Well-being, Income, Economic Development and Growth, NBER Working Paper, No. 16441, October. See also Ortiz-Ospina, E. & Roser, M. 2013, Happiness and Life Satisfaction, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction, (updated February 2024; accessed October 2024). Return to text

- Ortiz-Ospina, E & Roser, M 2013, Happiness and Life Satisfaction, Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/happiness-and-life-satisfaction, (updated February 2024; accessed October 2024). Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2024, Quarterly Productivity Bulletin – June 2024, 27 June, Canberra. Return to text

- ABS 2023, Education and Work Australia, Table 35. Return to text

- See Norton, A 2023, Mapping Australian Higher Education 2023, ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods, for a discussion. Return to text

- Ibid., p.52. Return to text

- See Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: From Learning to Growth , Vol. 8, Inquiry Report No. 100, Canberra, pp.4-6, for a discussion of literature and controlling for cofounders. Return to text

- Brennan, M 2022, Productivity, Migration and Skills , ‘Rebuilding Australia’s Future’, Universities Australia Conference, delivered 7 July. Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: From Learning to Growth , Vol. 8, Inquiry Report No. 100, Canberra, pp.4-6. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid, p. 3. Return to text

- Jobs and Skills Australia 2023, Towards a National Jobs and Skills Roadmap: Annual Jobs and Skills Report 2023 , Australian Government, October, p.18. Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: From Learning to Growth , Vol. 8, Inquiry Report No. 100, Canberra, Recommendation 8.4, p. 64. Return to text

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) 2023, 2022 Student Experience Survey , Department of Education, Table 1. Return to text

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) 2023, 2022 Student Experience Survey , Department of Education, Figure 1. Return to text

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) 2024, 2023 Employer Satisfaction Survey , Department of Education, Figure 1. Return to text

- Ibid., Table 3. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Brennan, M. 2022, Productivity, Migration and Skills , ‘Rebuilding Australia’s Future’, Universities Australia Conference, delivered 7 July. Return to text

- Quality Indicators for Learning and Teaching (QILT) 2023, 2022 Student Experience Survey , Department of Education, Figure 1. Return to text

- The PC recommended QILT data be refined and made more salient for prospective students. Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: From Learning to Growth , Vol. 8, Inquiry Report no. 100, Canberra, Recommendation 8.9, p. 111. Return to text

- Ibid., pp. 97-101. Return to text

- Ibid., Recommendation 8.9, p. 111. Return to text

- Williamson et al. 2015, Technology and Australia’s Future: New Technologies and their Role in Australia’s Security, Cultural, Democratic, Social and Economic Systems , Australian Council of Learned Academies. Return to text

- Susskind D 2024, Growth: A Reckoning , Penguin Books, United Kingdom, p.177. Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-Year Productivity Inquiry: Innovation for the 98% , Vol. 5, Inquiry Report no. 100, Canberra. Return to text

- Bloom et al. 2020, Are Ideas Getting Harder to Find? , American Economic Review, Vol. 110, No. 4, pp. 1104-1144. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Scannell et al. 2012, Diagnosing the Decline in Pharmaceutical R&D Efficiency , Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 191-200. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- O’Kane, M. et al. 2024, Universities Accord: Final Report, Australian Government, Figures 30 and 31. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid, p.192. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Ibid. Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-year Productivity Inquiry: From Learning to Growth , Vol. 8, Inquiry Report no. 100, p.49. Return to text

- O’Kane, M. et al. 2024, Universities Accord: Final Report, Australian Government, p. 299 Return to text

- Productivity Commission 2023, 5-Year Productivity Inquiry: Innovation for the 98% , Vol. 5, Inquiry Report no. 100, Canberra, Recommendation 5.4, pp. 50-52. Return to text

- See Sharma, I. et al. 2022, Piloting and Evaluating NSF Science Lottery Grants: A Roadmap to Improving Research Funding Efficiencies and Proposal Diversity , Institute for Progress, 2 February, for a summary. Return to text

- O’Kane, M et al. 2024, Universities Accord: Final Report, Australian Government, p. 216-217. Return to text

- Australian Research Council 2023, Discovery Projects Scheme: Two-stage Application Process , 30 October, https://www.arc.gov.au/news-publications/media/feature-articles/discovery-projects-scheme-two-stage-application-process (accessed October 2024). Return to text

- Sharma, I et al. 2022, Piloting and Evaluating NSF Science Lottery Grants: A Roadmap to Improving Research Funding Efficiencies and Proposal Diversity , Institute for Progress, 2 February. Return to text

- Norton, A. 2024, Australia made 9 changes to student migration rules over the past year. We don’t need international student caps as well , The Conversation, August 5. Return to text

Related publications